Lesson 1: Lab Fundamentals I

Measurement: Volume and Temperature

Another measurement that you will be doing frequently is to measure the volume of a substance. We often think only of measuring volumes of liquids, but all matter takes up space so all matter has a volume (even gasses!). We'll discuss how to take accurate volume measurements and then you'll get a chance to try it out in the lab. This section will also review measuring temperatures accurately and precisely.

Volumes of Liquids | Volumes of Solids | Temperature Measurements

Volumes of Liquids

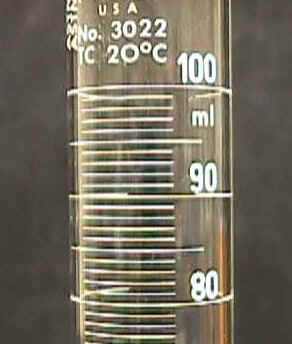

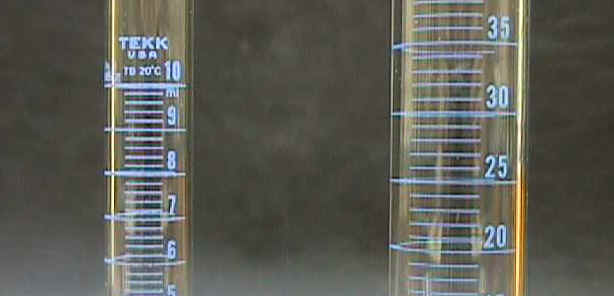

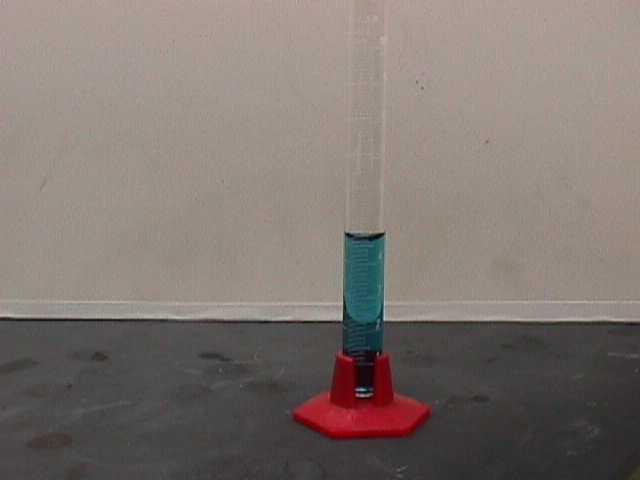

In this class, you'll most often measure the volume of a liquid using a graduated cylinder. There are other types of glassware that can measure volume but, for our purposes, graduated cylinders have enough precision as well as being relatively easy to use.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Meniscus

|

A characteristic of liquids in glass containers is that they curve at the edges. This curvature is called the meniscus. You measure the level at the horizontal center or inside part of the meniscus. With water in glass, the meniscus will curve up at the edges and down in the center so we say you read the bottom of the meniscus. The volume of liquid in this cylinder is 5.90 mL (not 6.10 mL!). One other important technique when measuring volume is to view the meniscus at eye level; if you read the volume looking down (or up) at an angle, you will not get an accurate reading. Don't lift the graduated cylinder up off the counter but instead sit, bend, or squat down so that the cylinder stays on the counter and you bring your eye level down to the read the level of the meniscus. |

|

There are some materials where the curve goes the other way. Still, you read the horizontal center of the meniscus. In this case it would be the top of the meniscus. |

|

|

|

|

|

Now, or when you are in the lab, read through the instructions and complete Exercise 29 in your workbook, and have an instructor check the volume measurements that you make.

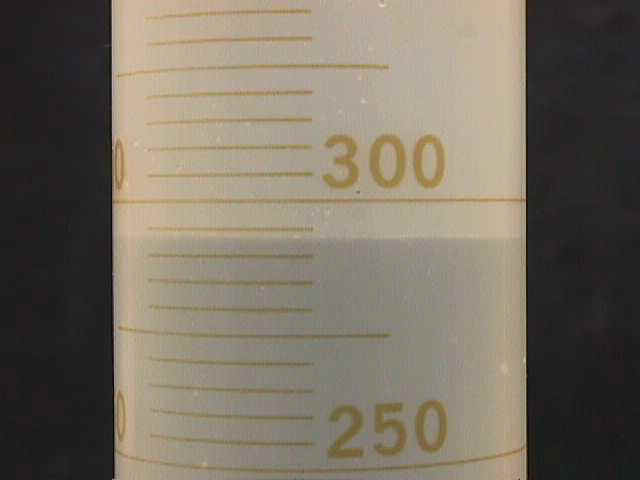

Volumes of Solids

|

|

|

|

The volume of a solid sample can also be measured by displacement. (Just be sure your solid won't dissolve in the water!) This usually involves

three steps:

|

|

|

1) measure the volume of liquid in a partially filled graduated cylinder, |

2) add the solid (making sure it is submerged) and note how the level of the liquid goes up, | 3) measure the combined volume of the solid and liquid. The difference between the initial and final volumes is the volume of the solid. |

Temperature Measurements

Another objective for this lesson is to use the Celsius or centigrade temperature scale to measure the temperature of fluids. Liquids and gases are both fluids.

|

|

|

|

|

These thermometers do not have to be shaken down. Quite a few laboratory thermometers have been broken by trying to shake them down next to a table.

It is best to hold a thermometer while using it. The container it is in may or may not be able to support it. All you have to do is put the thermometer in the liquid and watch the mercury or alcohol level change. When it stops changing, read the mercury level or the alcohol level if you use one of the red ones. That is your measurement. You don't have to wait a prescribed length of time, just let it come to a rest.

|

|

|

When you read them you should estimate between the lines, the same as you did with the length and volume measurements. Try to mentally divide the sections into 10 equal parts in order to read to a tenth of a degree.

Now, or when you come to the lab, do Exercise 30.