Lesson 7: Equilibrium Constants (Ka & Kb)

In this section, we'll be exploring equilibrium constant expressions for acids and bases. (You may remember equilibrium constants from an earlier lesson; we looked at solubility product constants for solutes in saturated solutions. The saturated solutions were in dynamic equilibrium because the rate of dissolution was the same as the rate of precipitation.)

Equilibrium Expressions for Acids and Bases | Calculations Involving Equilibrium Expressions

Equilibrium Expressions for Acids and Bases

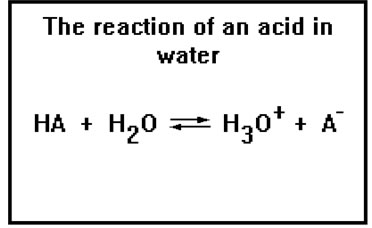

This reaction describes an acid donating its proton to water. The strength of the acid can be measured by measuring the concentration of the hydronium ions present at equilibrium.

As we noted before, this equation is often written:

HA

H+ + A-

The water, in addition to accepting the proton, is the solvent, and so is often not shown in the reaction, while H+ is a sort of shorthand for H3O+.

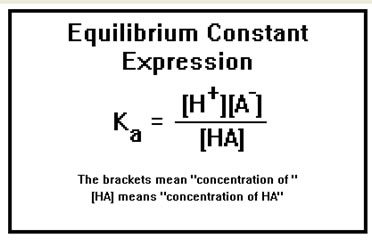

For any given acid, the product of the hydronium ion concentration times the A- ion concentration divided by the concentration of HA is a constant, called the equilibrium constant and is given the symbol Ka.

Since this equilibrium describes the dissociation of an acid, the equilibrium constant Ka is called an acid dissociation constant.

Equilibrium constant expressions can be written for any reaction and are often given special names that describe the type of reaction they pertain to. They always consist of product concentrations divided by reactant concentrations.

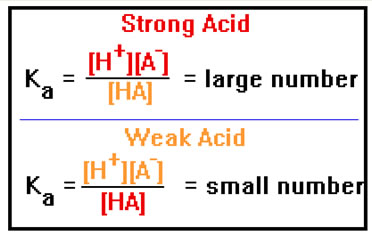

If HA is a strong acid, [H+] and [A-] will be high, while [HA] will be low, and so Ka will be a large number. If HA is a weak acid, the opposite will be true and Ka will be a small number.

|

Values of Ka range from 1012 all the way to 10-50, an enormous range. Most common acids, however, have Ka values in the range of 10-12 to 106. A strong acid generally is one in which Ka > 1. A useful classification says that strong acids are stronger than the H3O+ ion (Ka = 1), weak acids are weaker than the H3O+ ion but stronger than H2O (Ka = 10-14), while very weak acids are weaker acids than H2O. |

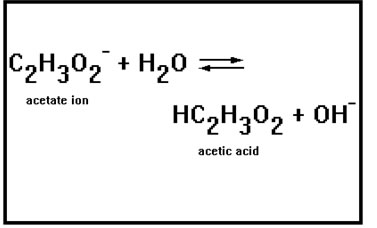

Just as equilibrium constants measure the strength of acids, they also measure the strength of bases. In this reaction, the acetate ion accepts a proton from water, thus acting as a base.

|

The acetate ion is the conjugate base of acetic acid, a weak acid, thus the acetate ion is a weak base. The reaction is shown with arrows going in both directions. |

|

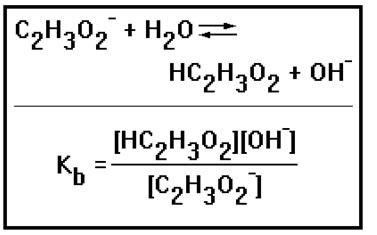

The equilibrium constant for this reaction is given the symbol Kb, and is often called the base constant. Like Ka, Kb will be large for a strong base and small for a weak base. |

Again, water is left out of the equilibrium constant expression because it is the solvent. Its concentration does not change appreciably as the reaction proceeds. Also, as with the Ka, the equilibrium constant expression is written by multiplying the product concentrations and dividing by the reactant concentrations. |

|

Exercise 7 in your workbook will give you some practice writing out equilibrium constant expressions for some acids and bases. Try that exercise now.

Answers to Exercise 7:

a. |

Ka = |

|

b. |

Kb = |

|

c. |

Ka = |

|

Example 8 in your workbook gives values of Ka and Kb for some common acids and bases. Note that as the Ka of the acids gets smaller (the acids get weaker), the Kb of their conjugate bases gets larger (the conjugate bases get stronger). All of the acids and bases in the list are considered weak.

Calculations Involving Equilibrium Expressions

In a solution of an acid, it’s not the concentration of acid, HA, that determines the acid strength of the solution, but the concentration of the free H+ (or H3O+) ion. This concentration is often expressed as the pH of the solution.

Similarly, the base strength of a solution is determined by the concentration of free OH- ions. The concentrations of these two ions are related. In fact, you might recall that the product of the two is equal to 1.0 x 10-14.

[H+][OH-] = 1.0 x 10-14

or

pH + pOH = 14.0

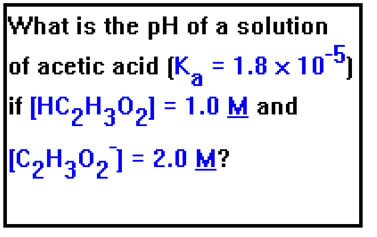

You can use the equilibrium constant expression to calculate the concentration of the hydronium ion in solution. Here is example 9a taken from your workbook. |

|

The equilibrium constant expression can be used in other ways as well, as we’ll see in the next few examples. For this problem, we want the pH. Recall that:

Therefore we will need to calculate [H+] first, then find its negative log to get the pH. |

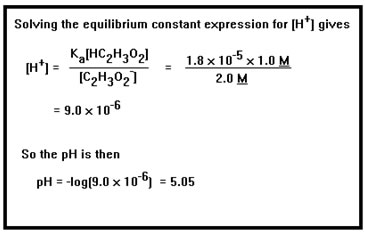

|

First we solve the equilibrium constant expression for [H+]. Then we substitute the values for the known concentrations and the Ka. Finally, we take the negative log of the result. In a logarithm, the significant digits are those that follow the decimal point. Since 1.8 x 10-5 has two significant digits, we keep two digits after the decimal point in the pH. |

|

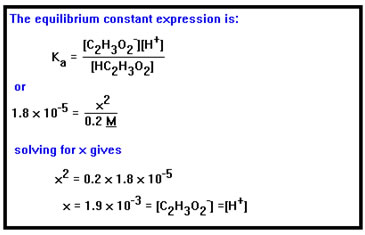

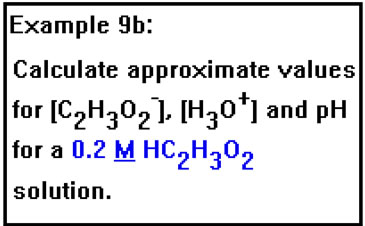

Example 9b asks for the acetate and hydronium ion concentrations and the pH of a 0.2 M solution of acetic acid. The pH can be calculated once we know the value of [H3O+], since pH is just the negative log of the hydronium ion concentration. To determine the concentration of the acetate ion we will make use of the fact that when the acid dissociates, it releases one acetate ion for each hydronium ion, thus the concentration of these two ions must be the same. We know the value of the Ka from the previous example. |

|

The concentration of acetic acid given, 0.2 M, refers to the concentration of the acid before it dissociates. Since this is a weak acid, we will start by assuming that only a very small fraction of the acid molecules dissociate so that, at equilibrium, the concentration of the acid is still very nearly 0.2 M. Acid concentrations are commonly given as the number of moles of acid in solution before any protons have been donated. Once the reaction has reached equilibrium, the amount of undissociated acid will depend on how strong the acid is. For a strong acid, this will be essentially zero. However, for weak acids, only a tiny fraction of the acid dissociates, so that the concentration of undissociated acid at equilibrium will be very nearly equal to its original value. |

|

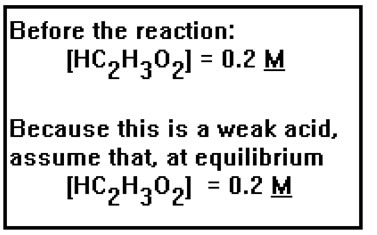

Since, when the acid dissociates, one acetate ion will be left behind each time one proton is donated, the concentration of acetate ions and the concentration of H3O+ ions will be equal. We’ll call the concentration x. In water there is a very small number of H3O+ ions present from the water itself. This is too small to matter unless the acid is very weak, that is, its Ka is less than about 10-14. Since the Ka for acetic acid is 1.8 x 10-5, we can ignore the small concentration of H+ ions from the water and our assumption that the number of hydronium ions is the same as the number of acetate ions is valid. |

|

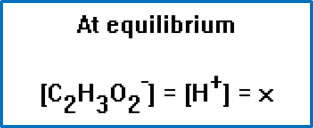

From the previous example, we know that Ka = 1.8 x 10-5. We can now substitute these values into the equilibrium constant expression and solve for x. This tells us both the acetate and hydronium ion concentrations. Since 0.0019 mol/liter of H+ ions are present, this same amount of acid must have dissociated, so that the actual concentration of acid is just 0.2- 0.0019, or 0.1981 M, not 0.2 M. This represents an error of less than 1%. Since we have the concentration to only one significant digit (0.2 M), an uncertainty of about 10%, our assumption is justified. |

|

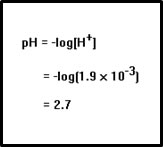

To calculate the pH, we simply take the negative log of the [H+]. The pH of this solution is 2.7. |

|

If you would like to see how to calculate the [H+] more accurately, taking into account both the dissociation of the acid and the presence of a small amount of H+ from water (and you are comfortable solving quadratic equations), ask the instructor when you visit the lab. |

|

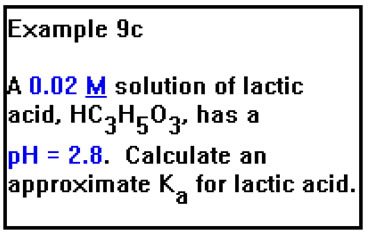

Our final example, 9c, asks us to find the value of Ka for lactic acid from a measurement of the pH of a solution of the acid of known concentration.

|

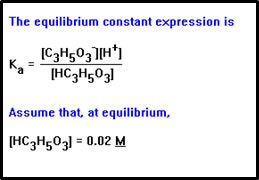

To calculate the value of the Ka, we will need the values of the concentration of lactic acid, lactate ion, and H+ at equilibrium. We will essentially work the previous problem in reverse, in the process making the same set of assumptions. |

We begin by assuming, as we did in the previous example, that the concentration of lactic acid is the same before and after equilibrium is established, 0.02 M. If all the lactic acid dissociated, the [H+] would be 0.02 M. The negative log of this number is 1.7. Since the pH of this solution is 2.8, we can assume we are dealing with a weak acid and that our assumption is reasonable. |

|

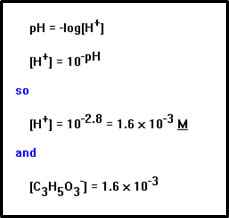

We can determine the [H+] from the pH. We can also assume, as before, that the concentration of lactate ions and the concentration of H+ ions will be the same, since each time a lactic acid molecule dissociates, one of the each ion is released. Again we ignore the small difference in these concentrations due to H+ ions from water. In general, the concentration of H+ ions from water will be less than 10-7 M, a good deal smaller than the 1.6 x 10-3 moles per liter of H+ from the acid. |

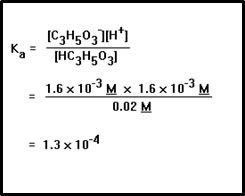

|

Now we substitute these values into the equilibrium constant expression to calculate Ka. Strictly speaking, we should round this answer down to 1 x 10-4 since the concentration of lactic acid was given to only one significant digit. Also, if you paid attention to the units in this problem, you noticed that the units of the answer are M, moles per liter, buth that we didn’t include them in the answer. |

|

Answers to Exercise 9:

9. a. [H3O+] = 9.0 x 10-6; pH = 5.05

b. [C2H3O2-] = [H3O+] = 1.9 x 10-3; pH = 2.72

c. Ka = 1.3 x 10-4

Exercise 10 in your workbook has a number of problems of this type. Try these before you move onto the next part of this lesson. You can find the answers below.

Answers to Exercise 10:

10.a. Ka = 4 x 10-8

b. pH = 2.10

c. HClO2 (it has the larger Ka)

d. 1 M HClO (it's the weaker acid)

e. [NH4+] = [OH-] = 1.3 x 10-3

f. [NH4+] = 1.8 x 10-4