Lesson 8: Molecular Lewis Diagrams (Part 2)

The method of predicting formulas for compounds described in the preceding "Molecular Lewis Diagrams (Part 1)" page is important but it is of limited value because it will predict only a limited number of the compounds that actually do exist.

For example, carbon and oxygen form two compounds. Nitrogen and oxygen form six or seven compounds. Chlorine and oxygen form four or five compounds. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

The limitations of this method stem from two assumptions. It assumes that the octet rule is completely valid, and that there are equal numbers of electrons from each element in the bonds. These assumptions work for the examples given so far, but are not true for many other compounds. In short, this method provides us with a good explanation of a limited number of simple compounds.

That leads us to another use of Lewis diagrams, making sense out of where the electrons are in formulas that we would not have predicted.

Deducing Lewis Diagrams | Practice | Electronegativity

Deducing Lewis Diagrams

There are many molecular compounds for which it is not easy to predict the formula based on the principles we've just been using. Even so, you will sometimes need to draw Lewis diagrams for them. One reason for doing this is to determine molecular shapes and properties. In such cases you will be given the name or molecular formula and be asked to draw the Lewis diagram for it. Sometimes that will be an easy task and the dots will just fall into place. Other times it will not be so easy. Let me give you some guidelines that can be used in such cases. Your textbook and other instructors use different approaches. So, if this method doesn't work for you, try one or more of the others.

Here are some guidelines. Pick a central atom, if there is one. Usually it is the one that needs the most bonds. Arrange the electrons of that central atom to meet the needs of the atoms around it. Then arrange the electrons of the surrounding atoms to meets the needs of the central atom. Also, think "covalent means co-operate." The atoms have to cooperate with one another to do covalent bonding. |

|

This approach is somewhat intuitive - presumably, you think like an atom and put your electron dots where they will best accommodate the atoms to which you will be bonding.

Other Approaches

Other, more systematic approaches can also be used. If you have trouble using the previous approach try using the "Systematic Approach" shown in example 6 in your workbook. Or you can get some additional help from an instructor or other students to work out an approach that works best for you.

Examples and Practice

You can work through a couple of examples using the method I have described. The formulas let you practice using the guidelines, or try using the other options. (These examples are also shown in examples 5 a-b in your workbook, and the practice is in exercises 5c-e and 7.)

The first example is another combination of carbon and oxygen. It has the formula of CO. So at this point, you know that there is only one atom of carbon and one atom of oxygen and all of the "octet rule satisfaction" that goes on has to come from just those two atoms. Either of these atoms could be considered the central atom.

Look at what's involved: the carbon atom has four valence electrons and needs four more electrons; the oxygen atom has six valence electrons and needs two more electrons. The carbon needs four more electrons! Where is it going to get them? From the oxygen.

The two electrons that the oxygen needs are going to come from the carbon, so redraw (follow the arrows in the workbook example) the electron dot diagrams to reflect what's going to happen to some of these electrons. Since the oxygen needs two electrons, draw the electron dot diagram for carbon with two electrons pointing toward the oxygen. Since the carbon needs four electrons from the oxygen, draw the electron dot diagram so that four of the oxygen's electrons are grouped together on the side that's facing the carbon atom. Then bring the symbols together to show the electron dot diagram for carbon monoxide. |

|

|||||||||

The trick here, if you want to call it that, is to focus on what the other atom needs when you are drawing dots around one atom. Put the dots around carbon in a way that fits what the oxygen needs to get from the carbon. Put the dots around oxygen in a way that fits what the carbon needs to get from the oxygen.

The formula for the next molecule is C2H4. The name is ethene, but that tells you nothing because you have not yet learned about naming organic compounds. You also need to know that the two carbon atoms are bonded together in the middle and that the hydrogen atoms are spread around them.

Again, put in the electron dots for the center atoms keeping in mind what the outside atoms need. Each carbon electron dot diagram has one dot pointed toward each hydrogen because each hydrogen needs one electron, and two electrons pointed toward the other carbon because the other carbon needs two electrons. Now draw in dots for the outside atoms taking into account what the central atoms need. Each of the hydrogen atoms has its dot pointed toward the carbon because each carbon will get one electron from each hydrogen. Bring them together and you've got the electron dot diagram for C2H4. |

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Practice

Now you should try your hand at working parts c, d, and e of exercise 5 in your workbook. The answers are shown in your workbook, but cover them up when you first try them. Then check your answers and compare your approach to the approach shown in the sequence of diagrams.

More Practice

After you have mastered the examples in exercise 5 using any of these methods, continue with the next set of practice problems.

Try your hand at drawing the electron dot diagrams for these compounds. (They are also shown in exercise 7 in your workbook.)

| SO2 | SO3 | N2O | N2O4 |

Note: S is in the center of the first two. A nitrogen atom is in the center of N2O. If you are interested, you might see how many possibilities you can come up with for that one. You might also try putting oxygen in the center if you would like. The two nitrogen atoms are in the center of N2O4.

Answers

| SO2 | SO3 | N2O | N2O4 |

|

·· ··

·· O : : S : O : ·· ·· |

·· : O : ·· ·· ·· O : : S : O : ·· ·· |

·· : N : : : N : O : ·· or ·· ·· N : : N : : O ·· ·· |

·· ·· :O: :O: ·· ·· ·· ·· O : : N : N : : O ·· ·· |

Electronegativity

Bond Polarity

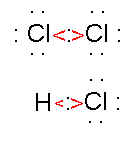

An important variation in covalent bonds is in the attraction exerted on the electrons by the two atoms that are bonded together. If there's an equal attraction from both atoms, then we have a nonpolar bond. If one atom exerts a stronger pull on the electrons than the other, then we have a polar bond. Of course, there is a wide range in the degree of polarity. |

|

Electronegativity

We have a name for the amount of pull that one atom exerts on the electrons that it is sharing with other atoms. It is called electronegativity.

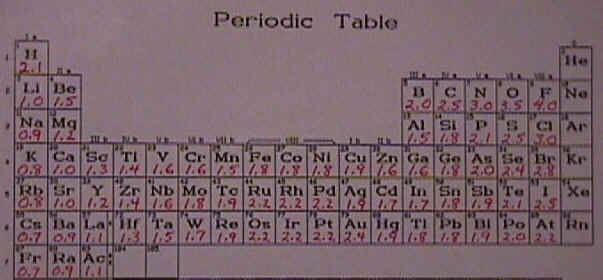

Electronegativity is useful for all elements on the periodic table but it is most useful for the nonmetals, which are shown here to the right. Electronegativity is more of a concept than a property. As such, values for it are estimated or calculated rather than measured. Over the years, chemists have come up with a variety of ways of calculating values for electronegativity, and also a variety of values. Here is one particular set of values. . |

|

Look at how the electronegativity changes as you go across and up and down the periodic table (for nonmetals,above right, and all elements, below). No values are given for the inert gases because they do not bond readily to other atoms. We cannot talk about how strongly they attract electrons when they bond, if they don't bond. (Actually, a few do form bonds with fluorine and oxygen, but only with difficulty.)

The electronegativity generally increases as you go from left to right across the periodic table. It decreases as you go down the periodic table.

I think you can see that the reason for this is going to depend on those same factors that we used to explain the trends in atomic size, ionization energy, and electron affinity.

First, the horizontal comparison. As you go across a period from left to right, the atoms of each element all have the same number of energy levels and the same number of shielding electrons. Thus the factor that predominates is the increased nuclear charge. When the nuclear charge increases, so will the attraction that the atom has for electrons in its outermost energy level and that means the electronegativity will increase.

Now what about the vertical comparison? As we established previously, when you go from one atom to another down a group, you are adding one more energy level of electrons for each period. The increased shielding nearly balances the increased nuclear charge and the predominant factor is the number of energy levels that are used by the electrons. So as you go from fluorine to chlorine to bromine and so on down the periodic table, the electrons are further away from the nucleus and better shielded from the nuclear charge and thus not as attracted to the nucleus. For that reason the electronegativity decreases as you go down the periodic table.

You might have noticed that there are some high values in the middle of the transition group. Those elements have fairly high electronegativities for metals. The reason for that ties in with the arrangement of electrons and the fact that the atoms are using d orbitals. The way that the d orbitals are shielded is different than the way that s and p orbitals are shielded so there is some variation in the transition metals that is not as easily explained as the general trend that I have just been talking about.

Practice

Take a moment to do parts b, c, d, and e of exercise 19 in your workbook.

Electronegativity - Continued

So far, our comparison of electronegativities has been limited to left and right comparisons within a period and vertical comparisons within a group. Sometimes you have to make comparisons of elements that are not both in the same period or both in the same group. One way is simply to look up values for electronegativities of the elements you are comparing. Another way of remembering how the electronegativities of nonmetals compare is by using the word FONClBrISCHP. It has a spelling that corresponds with the symbols of many of the nonmetals in decreasing order of electronegativity. F for fluorine, O for oxygen, N for nitrogen. Those are the 3 most electronegative elements. Chlorine is very close behind nitrogen, perhaps they are tied. athough the difference in atomic size does come into play (chlorine is larger than nitrogen). Then comes bromine, iodine, followed by sulfur, carbon, hydrogen, and phosphorus. So FONClBrISCHP is a very useful word in helping you remember the order of the electronegativities of the nonmetals.

We can use electronegativity to predict and explain the polarity of bonds between pairs of atoms.

For example, the bond between hydrogen and chlorine is a polar covalent bond because chlorine is significantly more electronegative than hydrogen so chlorine has a stronger pull on the electrons than does hydrogen. The bond between carbon and oxygen is also a polar covalent bond because oxygen is more electronegative than carbon. The bond between two hydrogen atoms is a nonpolar covalent bond because each atom has the same electronegativity. Because the electronegativities of chlorine and bromine are only slightly different, the bond between them is slightly polar. |

|

Practice

Determine the polarity of the bonds shown in exercise 20 in your workbook. The answers follow.

Answers

P-F is a polar bond. F-F is a nonpolar bond. H-O is a polar bond. H-C is a very slightly polar bond. There is not much difference between the electronegativities of hydrogen and carbon. C-C is a nonpolar covalent bond. If you had trouble with any of those be sure to check with an instructor to figure out why.

Comparing Covalent and Ionic Bonding

Let's push some of these ideas a bit further. By looking at electronegativity we can talk about gradations in metallic and nonmetallic character. Although there are many inconsistencies, we can generalize that metals have low electronegativities (generally below 2) and nonmetals have high electronegativities (generally above 2). We can also generalize about ionic and covalent bonding in this way. Covalent bonding results when there is a small difference in the electronegativities of the two elements. Ionic bonding results when there is a very large difference in electronegativities between the two elements. Some chemists set the dividing line between a small difference and a large difference at about 1.7 to 1.9.

If we select pairs of elements, such as those shown here (and also in example 21 in your workbook), and compare how different their electronegativities are, you get a wide range of differences. Consequently, you get a gradation of bond types. Not just covalent and ionic, but nonpolar covalent, slightly and very polar covalent, slightly ionic and very ionic. Covalent and ionic bonding can be viewed as extremes on a continuum rather than just different types of bonds. As differences between electronegativities become larger, the bonds become more ionic. As the differences become smaller, the bonds become more covalent. |

|

This approach works well if one or both of the elements is a nonmetal. In a later portion of this lesson we will look at what happens when the bonding involves just metal atoms.