Lesson 8: Other Covalent Materials

Covalent bonding can result in the formation of more than just molecular compounds. In this section we will consider pure elements, covalent networks, semiconductors, free radicals, and polyatomic ions.

Elements | Covalent Networks | Semiconductors

Free Radicals | Polyatomic Ions

Elements

Some differences between covalent and ionic bonding have already been mentioned. Here is another one. It is possible for covalent bonding to occur between atoms of the same element. That is not possible with ionic bonding. With ionic bonding you need to have two different elements, one to lose electrons and one to gain electrons. The atoms involved in covalent bonding all need to gain electrons and they do not have to be different elements. So let's look at covalent bonding in pure elements. (Ex. 12 in your workbook)

Let's start with the simplest case, a hydrogen atom bonding to another hydrogen atom. Each has one electron and wants one more. By coming together, each can "gain" one electron from the other. Since neither atom lets go of its electron, the two atoms are bonded together by their mutual attraction for the shared pair of electrons |

|||||

H2 is an element because it contains only hydrogen atoms. H2 is a molecule, no additional bonding is needed. There are two atoms in the molecule so it is a diatomic molecule. Hydrogen is one of several elements that form diatomic molecules. |

|

||||

Nitrogen atoms have five valence electrons and need three more. They are small and have a strong attraction for electrons. Thus when a nitrogen atom bonds to another nitrogen atom, each atom can attract three of the other's valence electrons and form a triple bond. Three elecrons from each atom get lined up between the atoms. |

||||||

Although that could be represented as shown in the middle diagram, triple bonds are not written this way. Generally they will be written with the three pairs of electrons arranged as shown in the bottom diagram. (Or with three parallel lines from one N to the other, shown in your workbook, ex. 12b.) So the nitrogen molecule, which can be written as N2, has a triple bond. |

|

|||||

Practice with Diatomic Elements

Now see what you can do with O, F, Cl, Br, and I. You can check your results below to make sure you have them correct.

Answers

Here you can see the Lewis diagrams for these elements.

|

·· ·· O : : O ·· ·· |

·· ·· : F : F : ·· ·· |

·· ·· : Cl : Cl : ·· ·· |

·· ·· : Br : Br : ·· ·· |

·· ·· : I : I : ·· ·· |

Elements Continued

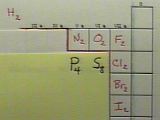

These seven elements (H, N, O, F, Cl, Br, and I) are called the diatomic elements because, as pure elements, they form molecules containing two atoms. You should commit these seven diatomic elements to memory. However, as you have already noticed, there are not necessarily two atoms of these elements in the molecules formed when they make compounds.

Oxygen also forms a molecule called ozone that contains three atoms. If you have not already checked out the diagram shown, see if you can figure out a good Lewis diagram for O3. |

|

| Phosphorus and sulfur are not diatomic elements. They generally form molecules of P4 and S8 although other forms of these elements also exist. In part this is because they form single bonds rather than the triple and double bonds found in N2 and O2. Phosphorus and sulfur atoms do not have a strong enough pull on electrons to form multiple bonds by themselves. Check with your instructor if you are interested in how these molecules are put together. |

|

Covalent Networks

| Boron, carbon and silicon form networks rather than molecules in their pure states. You should commit that fact to memory. |

|

Look at the electron dot diagram for carbon. (This sequence is also shown in example 13.) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

We can show the bond between this atom and another carbon in this way. But notice that this doesn't satisfy the octet rule for this first carbon atom. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

To do that we'd need another carbon atom and another and another. Then each of those carbon atoms would need another and another and another and another and another and so on. This pattern, which is shown here in two dimensions, actually exists in three dimensions. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It is the diamond form of carbon, which is shown here. This model is also in the lab for you to look at when you are there. It has the same pattern of atoms as the diagram above, except that two colors are used to reperesent the carbon atoms. |

|

However, if you start taking a look at the different dimensions of this thing, you can see that quite a different set of patterns arise. The reason for the different colors in this model is to emphasize certain bonding patterns. You can see that there are planes or layers of atoms. |

|

In the orientation shown to the right, you can see that the light ones are a little bit higher than the black ones. So you can see that it is a matter of position, rather than types of atoms. But that gives you a picture of what the diamond arrangement is like. Notice that each carbon atom is bonded to four other carbon atoms. |

|

Another form of carbon is graphite and its arrangement can be envisioned by taking the puckered planes of atoms from the diamond form and making them flat. If you do that, then you end up with the graphite form of carbon. The atoms are arranged slightly differently. From the side you can see that the graphite has planes of carbon atoms that are somewhat more distant from the next plane than was the case with diamond. That is what gives graphite its slippery quality. This plane of atoms can slide on this plane of atoms because they are not quite so strongly bonded. |

|

By changing the angle of view, you can see a hexagonal pattern. From this angle, it looks very much like the diamond. These are the two most common forms of carbon. Diamond and graphite. |

|

Another form of the element carbon that is not as common but is making news are the Buckminsterfullerenes, also called Bucky balls, which contain clusters of carbon atoms. This particular model emphasizes the bonds. Each point where the bonds come together represents a carbon atom. These Bucky balls each contain about sixty carbon atoms, some contain 60, some 70, some 72. This is a form of carbon that has been making the news during the past several years. Carbon "nanotubes" are another form of Bucky balls, but with a tubular shape rather than a ball shape. |

|

Models of these different forms of carbon are available for you to look at when you are in the lab.

Silicon has essentially the same bonding pattern as diamond. Diamond, graphite and silicon are important enough materials that you should specifically remember that they are covalent network materials.

Comparing Molecules and Networks

Another common covalent network material is the compound silicon dioxide, SiO2, also known as quartz. It is a covalent network material even though its formula is very similar to that of carbon dioxide which is a covalent molecular material. Why is the bonding arrangement so different?

Take another look at carbon dioxide, CO2, which we've talked about before. (It is also shown in example 15-a.) Because a carbon atom is smaller and has a greater pull on electrons than a silicon atom, its four electrons can be concentrated into two double bonds to the oxygen atoms. |

··

·· |

Because silicon is larger and has less pull on its electrons, its electrons are spread out in four single bonds with four oxygen atoms. (Also shown in example 15-b.) This leaves each oxygen atom with the ability, actually, the necessity to bond to other atoms. Each oxygen atom shown here will bond to another silicon atom (shown in example 15-c), and each silicon atom will bond to more oxygen atoms. You can imagine that the network of covalently bonded silicon and oxygen atoms can continue indefinitely. |

· |

If you look carefully at this three-dimensional model of quartz, you can see that the bonding is quite extensive. This three-dimensional model of quartz is in the lab so that you can look at it first hand when you are in the lab. At that time, you can also see that the alignment of the atoms parallels the faces of a quartz crystal. |

|

Let me summarize a few points about covalent materials. If you have covalent bonding, you may have elements or compounds. Also, you may have either network or molecular materials. Usually it will be molecular. The only examples of network covalent bonding that you have to worry about for this course are carbon, in the form of diamond and graphite, silicon, and silicon dioxide, SiO2, which is commonly known as quartz. Any material in this course which has just covalent bonding other than graphite, diamond, silicon, or quartz, will be a molecular material. |

|

Semiconductors

While I'm talking about silicon and covalent network materials, let me deal with the special case of semiconductors. |

|||

Silicon is a network marginal nonmetal. It can be represented using electron dot diagrams in this way. This is a two dimensional drawing rather than three, but it will serve for our purposes. Around the edge I've shown the pairs of electrons that would result from this atom bonding to the next atom over. Pure silicon is an intrinsic semiconductor, but impurities enhance its properties. |

|

||

What if an atom from a neighboring family like phosphorus or arsenic took the place of one of the silicon atoms? |

|||

Phosphorus has five valence electrons, which is normal for it, but the bonding network is set up using 4 valence electrons from each atom. In that sense the fifth valence electron of the P is an "extra" electron, it is not "tied down" like the rest, it is somewhat free to move around, it increases the electrical conductivity of the network. Since the electron is negative, we have what is called a negative or n-type semiconductor. |

|

||

Conversely, what would happen if an element like Al or Ga from the family to the left of Si on the periodic table were used to replace one of the silicon atoms? |

|||

Ga has only 3 valence electrons. Again that is normal for Ga, but in a network that is set up using 4 valence electrons from each atom that leaves a gap. Because it represents no charge where there "should be" a negative charge, it is often referred to as a "positive hole." |

|

||

The "hole" also offers a place to which neighboring electrons can move. When they do move, it is almost like the hole moved. Because the electrons can move a little, electrical conductivity is increased. Because it seems like the "positive hole" is moving, this is called a positive or p-type semiconductor. |

|

||

By carefully manipulating the size and location of the n-type and p-type regions in a chip of silicon or the similar metalloid germanium, a wide variety of diodes, transistors and other electronic components have been created.

Free Radicals

Sometimes we have to deal with atoms or molecules that don't have all of their electrons paired up or bonded. We call these free radicals.

One example is the chlorine free radical that has been implicated in the

destruction of ozone in the upper atmosphere. |

· : Cl : ·· |

Another example is the hydroxyl free radical that can result when water

molecules are broken apart by radiation or other reactions. This happens in our bodies

often enough that we have certain enzymes dedicated to reacting with hydroxyl free

radicals. |

· : O : ·· H |

A third is nitrogen dioxide, one of the components in smog. A variety of Lewis diagrams can be drawn for this one, but they all seem to end up with one unpaired, unbonded electron. |

·· ·

·· : O : N : : O ·· ·· |

In each of these examples it is the unpaired, unbonded electron that makes these free radicals so reactive. These atoms and molecules have room for and a strong attraction for an additional electron. They can react with a wide variety of other chemicals to gain electrons.

Practice Identifying Free Radicals

To give you just a little practice working with free radicals, take some time now to identify the free radical in each of the following pairs of chemicals. Also, draw a Lewis diagram that illustrates why that chemical is a free radical. (This is also given in exercise16 in your workbook.) Answers follow.

| CO or NO |

| chlorine atom or chlorine molecule |

Answers

| NO |

··

·· · N : : O ·· |

| chlorine atom |

· : Cl : ·· |

Polyatomic Ions

Let's touch upon polyatomic ions again. They are chemicals in which atoms fill their octet with electrons by using both covalent and ionic bonding. A simple example of this is the polyatomic ion, hydroxide. (The way that it can be formed is also shown in example 17 in your workbook.)

Oxygen can fill up its "octet" using three different options. The ionic option (left side) involves the atom gaining two electrons to become an ion with a -2 charge. The covalent option (right side) involves the atom sharing two electrons from other atoms (hydrogen in this case). |

|

The polyatomic ion option (middle) requires the oxygen atom to obtain one electron by sharing with another atom (hydrogen in this case) and gain the other electron by taking it away from some willing electron-losing atom. |

|

In hydroxide ions, the shared electrons create a covalent bond which holds the oxygen and hydrogen atoms together. The gained electron makes this combination of atoms an ion. The attraction between the negative charge on this ion and the positive charge on other ions results in ionic bonding between this ion and others. This situation is typical of polyatomic ions--covalent bonding holds the atoms together within the ion and ionic bonding joins the entire ion to other oppositely charged ions. |

|

Practice Determining Charge from "Extra" Electrons

It is possible, given the right information, to figure out the charge on polyatomic ions. I'd like you to try to figure out what charge there should be on each of the polyatomic ions shown here (and in exercise 18 in your workbook). However, you should already know what charge each has. So what you actually have to do is match or verify the charge for each with the Lewis diagram.

|

·· : O : ·· ·· ·· : O : S : O : ·· ·· ·· : O : ·· |

·· : O : ·· ·· ·· : O : P : O : ·· ·· ·· : O : ·· |

H ·· H : N : H ·· H |

|

··

·· : O : N : O : ·· :: ·· : O : |

··

·· : O : C : O : ·· :: ·· : O : |

·· : O : ·· H |

To do this, start with what you know about how many valence electrons each atom has, and compare that to the number of electron dots shown in each of the diagrams. If there are more dots shown than can be accounted for by the number of valence electrons that those atoms should have, then the polyatomic ion as a whole will have a negative charge equal to the number of additional electrons. If it's short some electrons, then it will have a positive charge equal to how many electrons that it's short. After you have figured those out, compare your answers to the known charges. If you don’t want to look them up, they are listed below.

Answers

The charge on SO4 is -2. The charge on PO4 is -3. The charge on NH4 is +1. The charge on NO3 is -1. The charge on CO3 is -2. The charge on OH is -1.