Lesson 9: Intermolecular Bonds

The molecular property that determines which type of intermolecular bond can exist between two molecules is called polarity. A polar molecule is one in which one side of the molecule is slightly positively charged and the opposite side is slightly negatively charged. A polar molecule is said to possess a “dipole,” that is, two poles, one positive and one negative.

A polar molecule has at least two atoms bonded together that have significantly different electronegativities. The bond between them is a polar bond because the electrons are not shared equally. (As we will see, however, to be a polar molecule, it is not sufficient merely to have a polar bond.) Most often one of these atoms is a nitrogen, an oxygen, or a fluorine atom. The other halogens – chlorine, bromine, and iodine – are not as electronegative as O, N, or F, and so molecules containing these halogens are usually not very polar. None of the other nonmetals is sufficiently electronegative to make a molecule polar.

In this section we'll look at how the different types of intermolecular bonds are related to a molecule's polarity. We'll examine how to determine the polarity of a molecule in a later section of the lesson.

Dipole-Dipole Bonding | Hydrogen Bonding | van der Waals Bonding

Dipole-Dipole Bonding

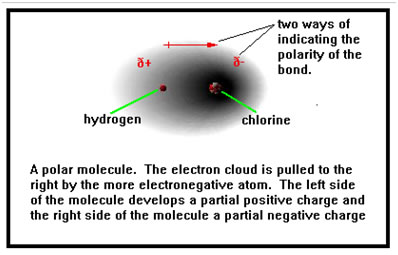

The figure shows the simplest of polar molecules: two atoms sharing electrons unequally. The more electronegative atom on the right has a greater share of the electrons and thus a denser electron cloud. The resulting dipole can be shown using plus and minus signs, or by an arrow.

Although we use plus and minus signs to show that the left side of this molecule is positively charged compared to the right side, the two atoms do not have full charges of +1 and -1 as they would if this were an ionic bond. The symbol d indicates that the positive and negative charges are fractions of a full charge. The closer together the two atoms are in electronegativity, the smaller the fraction of charge each atom has and the less polar the bond.

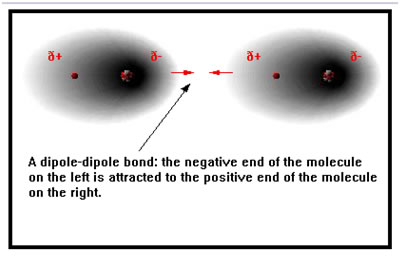

When two polar molecules get near each other, the positive end of one attracts the negative end of the other. This attraction between the two dipoles is known as a dipole-dipole bond.

It is precisely because the charges on the two atoms in a polar bond are not full +1 and -1 charges that a dipole-dipole bond is not nearly as strong as an ionic bond. This is particularly true when dipole-dipole bonds are compared to ionic bonds between ions that have charges greater than +1 or -1.

This brings up a very important point - none of the intermolecular bonds is as strong as an interatomic bond. In fact, it is perhaps unfortunate that they are called "bonds" at all; calling them intermolecular "attractions" would emphasize that they are much weaker than any of the interatomic bonds. However, the scientific community calls them intermolecular bonds and so you must remind yourself when you are studying this lesson that all intermolecular bonds are "attractions" between molecules, and weaker than the interatomic bonds.

Hydrogen Bonding

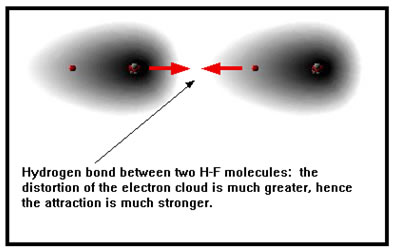

When the polarity of a molecule is caused by a bond between a hydrogen atom and either a nitrogen, an oxygen, or a fluorine atom, the resulting intermolecular bonds are unusually strong and so are given a special name: hydrogen bonds.

Hydrogen bonds are the strongest of dipole-dipole bonds. F, O, and N are the three most electronegative atoms in the periodic table and this is part of the reason why the bonds between hydrogen and F, O, or N are the most polar of covalent bonds. The strong polarity of these bonds results in strong dipole-dipole bonds between the molecules.

The only molecule that contains an H-F bond is HF. On the other hand, there are many molecules that contain H-O and/or H-N bonds are are therefore capable of intermolecular hydrogen bonding.

The hydrogen atom has only one electron, which it shares with the atom it is bonded to. When this electron is pulled strongly towards a highly electronegative N, O, or F, the positive hydrogen nucleus is highly exposed and is therefore much more strongly attracted to electrons on an atom of a neighboring molecule. |

|

In addition to “exposing” the hydrogen nucleus, N, O, and F have a relatively large fraction of a negative charge because they are so electronegative. Each of these atoms also has at least one lone pair of electrons that extends out from the atom. A hydrogen bond is the result of the attraction between a lone pair of electrons on a negatively charged F, O, or N and the exposed nucleus of a hydrogen bonded to another F, O, or N. |

|

van der Waals Bonding

This image shows the average location of the electrons in a nonpolar molecule. The electrons are shared equally, neither end of the molecule is positive or negative, so no dipole-dipole bonding is possible.

Nonpolar bonds like these are found when two atoms bonded to one another are either the same, or have similar electronegativies. The most common examples of atoms with very similar electronegativities are carbon and hydrogen, and chlorine and nitrogen. As a result, C-H and Cl-N bonds are almost completely non-polar. Bonds between carbon and chlorine, carbon and bromine, and carbon and iodine are also only very slightly polar. |

|

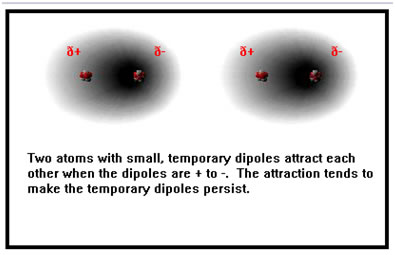

But electrons are in constant motion, and there are brief periods of time in which they are slightly to one side of the molecule or the other. During this time, the molecule has a very slight, temporary dipole. If another, similar, temporary dipole exists in a neighboring molecule, the weak mutual attraction causes the two dipoles to persist for slightly longer than they otherwise would, and the two molecules remain attracted for a short period of time.

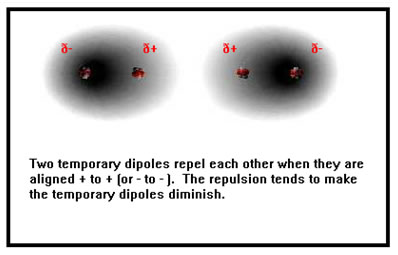

If, on the other hand, a temporary dipole of opposite polarity exists in a neighboring molecule, the two repel each other slightly, but this repulsion tends to remove the temporary dipoles more quickly than they otherwise would be.

The result is that the weak attractions last a bit longer than the weak repulsions, and the net effect is that there remains overall a very weak attraction between the two molecules. This very weak attraction is called a van der Waal’s bond.

|

|

Van der Waals bonds tend to be stronger when the atoms or molecules involved hold their electrons more loosely. The easier it is for the electron cloud to be distorted and form a temporary dipole, the stronger the van der Waals bonds will be. This property is called polarizability, and it is greater for larger atoms and molecules and for atoms with low electronegativity.

To summarize, there are three types of intermolecular bonds, all much weaker than interatomic bonds. The strongest are hydrogen bonds that form between molecules that contain an H-N, an H-O, or an H-F bond. Next are dipole-dipole bonds between polar molecules. The weakest are van der Waal’s bonds between nonpolar molecules.

It is sometimes confusing to students that hydrogen bonds, which are intermolecular bonds, only form between two molecules that include H-N, H-O, or H-F bonds among their interatomic bonds. It is the internal structure of a molecule that determines what kind of associations it can make externally, that is, to other molecules.

Similarly, it is the internal structure of a molecule that determines whether it is polar or nonpolar, and that, in turn, determines what kinds of external bonds (dipole-dipole or van der Waals) it can form with other molecules. Finally, we have only considered the kinds of intermolecular bonds that form between identical molecules. With one exception, namely ion-dipole bonds, we will not be concerned with the kinds of intermolecular bonds that form between dissimilar molecules.