Lesson 1: Molecular Weights and Mixtures of Gases

In this last section, we'll study how to determine the molecular weight of a gas and also look at one more gas law, Dalton's Law of Partial Pressures, which has to do with mixtures of gases. Finally, there are a few notes about this week's main lab experiment at the end of the section.

Molecular Weights of Gases | Dalton's Law of Partial Pressures | Lab Work

Molecular Weights of Gases

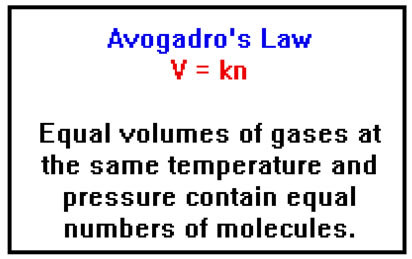

Avogadro’s Law originally stated the equal volumes of gas at the same temperature and pressure contained equal numbers of moles of gas. This meant that one could measure the number of moles of a gas simply by measuring its volume.

Actually, Avogadro didn’t determine the number of moles – or molecules – of gas in his samples. All he needed to do was to be able to compare the number of moles of gas in one sample to the number of moles in another. It was sufficient to know, for example, that molecules of hydrogen and oxygen gases combined in a two to one ratio to form water, and that for every two molecules of hydrogen that reacted, two molecules of water were formed. These “combining ratios” allowed Avogadro to determine the molecular formulas of hydrogen, oxygen, water, and many other gases.

|

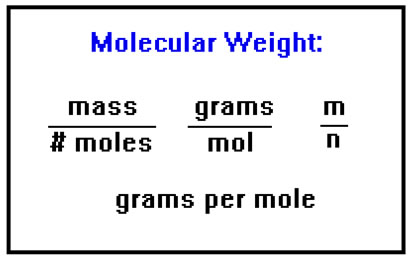

The discovery of Avogadro’s Law led to the first measurements of molecular weights, since if we know the mass of a sample of gas and the number of moles it contains, it’s a simple matter to calculate its molecular weight. The “combining weights” Avogadro determined are proportional to molecular weights. It was not yet possible to actually “count” atoms or molecules. (You might recall that we utilized this law in an experiment in CH 104.) |

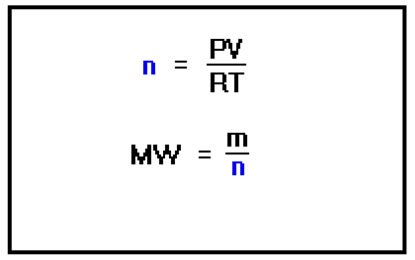

To determine the molecular weight of a gas, we measure the volume, temperature, and pressure of a known mass of a gas. We can use the Ideal Gas Law to calculate the number of moles of gas we have, and then divide this number into the mass to get the molecular weight. |

|

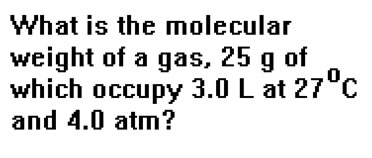

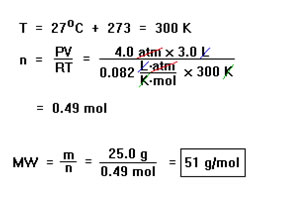

Suppose, for example, that 25.0 g of a gas occupies a volume of 3.0 liters at 27 oC and a pressure of 4.0 atm. What is the molecular weight of the gas? This is the first problem in Example 29b from your workbook. The first part of the solution, determining the number of moles of gas in the sample, is just another example of the first kind of Ideal Gas Law problem we described in the last section – a “one set of conditions” problem in which you calculate one quantity given values for the other three. |

|

First we change 27 oC to 300 K. Then, solving the Ideal Gas Law for n and substituting, we find that the number of moles of gas is 0.49 moles. Dividing this number into 25.0 g gives us the molecular weight, 51 g/mol. Since the pressure and volume both have two significant digits, our answer will be restricted to two significant digits. Notice how the units cancel to give the expected units for a molecular weight: grams per mole. |

|

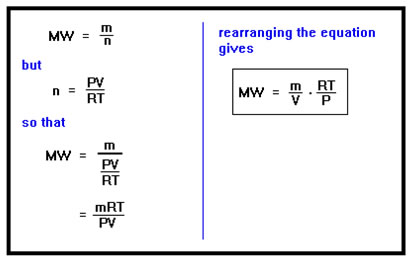

The molecular weight of a gas is its mass divided by the number of moles. The number of moles of a gas is just PV/RT. Making this substitution and rearranging gives the equation to the far right. With a little algebra, we can rearrange the equations to lead to a somewhat more convenient method of determining the molecular weight. We start with the definition of molecular weight, mass divided by the number of moles, and substitute for the number of moles using the Ideal Gas Law. The last step is just a simple rearrangement of the various terms in the expression to isolate the mass and volume terms. Do you recognize what these two terms now represent? |

|

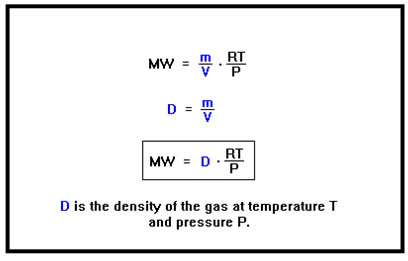

Notice that m/V is just the density, so that the molecular weight of a gas is related to its density. We can calculate the molecular weight of a gas given its density if we know the temperature and pressure at which the density was measured (and, of course, the value of the gas constant, R). Here, we simply substitute density for the ratio of mass to volume; that is, in place of m/V, we write D. Gases are quite compressible so that their density depends on the ratio of the temperature to the pressure. The RT/P term in the second equation takes these variables into account. |

|

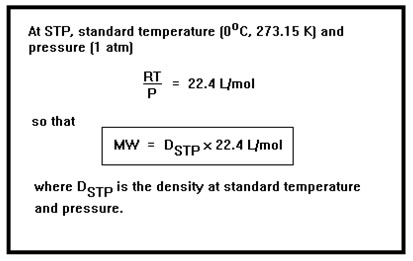

At STP (standard temperature and pressure), the value of RT/P is 22.4 L/mol. This, in fact, is the volume occupied by one mole of gas at STP. So the molecular weight of a gas is equal to 22.4 times its density at STP. The volume of an ideal gas is V = nRT/P. If we assume one mole of gas, then n=1 and this equation becomes V = RT/P, which is just the second half of the equation for the molecular weight. At STP, T=273.15K and P=1 atm, so that the volume is just 22.4 L. This is the volume of one mole of an ideal gas at STP. |

|

Example 29 in your workbook contains a sample of this kind of calculation. You should review this problem before you move on. Problem 2 in Example 29b asks you to compute the molecular weight of a gas based on its density, 5.00 g/L at STP. Try to work the problem on your own before looking for hints in your workbook.

Exercise 30 in your workbook contains some practice problems involving molecular weight for you to try. You will find the answers below. These problems are similar to the two problems in Example 29. You should be able to work them easily; if not, be sure to get some help from your instructor. (Don’t forget to think about significant digits when you get to the final answer for each problem.)

Answers to Exercise 30:

a. 48 g/mol

b. 49.5 g/mol

Dalton's Law of Partial Pressure

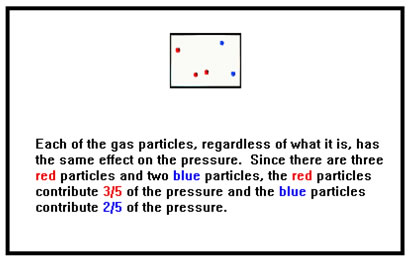

One of the assumptions of the Kinetic Molecular Theory is that gas particles simply bounce off of each other without interacting in any way. This means that the identity of the gas particles does not influence their PVT behavior.

Many gases are, like air, homogeneous mixtures of several gases. Because the gas particles do not interact in any way other than bouncing off each other, each gas particle has exactly the same influence on the gas law properties (P, V, T, and n) of the gas. One mole of nitrogen will exert the same pressure as a mixture of a tenth of a mole each of ten different gases under the same conditions of temperature and volume, assuming, of course, that the gases all behave like ideal gases. |

|

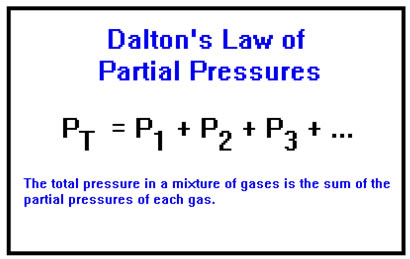

This led John Dalton to propose that, in a mixture of two or more gases, each one behaves just as if it were the only one in the container, exerting a pressure called its partial pressure. The total pressure in the container is then just the sum of these partial pressures. This is called Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures.

The partial pressure of a gas is the pressure it would exert if it were the only gas in the container; and, in fact, this is the pressure that it does exert. This is a behavior of gases which obey the Ideal Gas Law. As long as the assumptions of the Kinetic Molecular Theory are valid, Dalton’s Law describes the behavior of mixtures of gases.

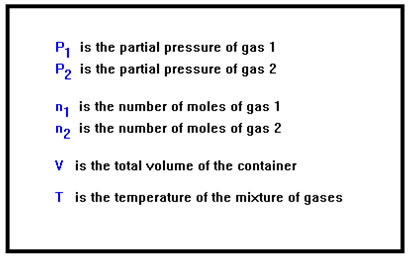

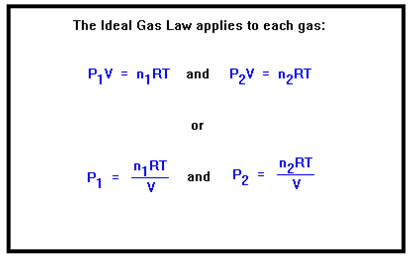

Each gas in a mixture obeys the Ideal Gas Law just as if it were the only gas in the container. For example, in a mixture of two gases, gas 1 and gas 2, P1 and P2 are their partial pressures, and n1 and n2 are the numbers of moles of the two gases, respectively. Since they are mixed together, each one occupies the entire volume of the container, V, and they both must be at the same temperature, T. Each gas can occupy the entire volume of the container only if the other gas molecules take up no room at all. This, if you remember, is one of the assumptions of the Kinetic Molecular Theory. Dalton’s Law would also not be valid if the molecules of one gas bound to or reacted with those of another gas in the mixture; but this, too, would violate one of the assumptions of the Kinetic Molecular Theory. |

|

We can write the Ideal Gas Law for each gas separately. That is, each gas in a mixture obeys the Ideal Gas Law. Its volume is the entire volume of the container, which is the same for every gas in the mixture. Its temperature is the same as the temperature of all the other gases. The pressure and the number of moles, however, are the values that apply only to that gas, and so have subscripts in the Ideal Gas Law indication which gas we mean. |

|

Example 36a in your workbook shows a simple problem involving Dalton’s Law. Take a look at that problem now and be sure you understand it before you continue. This is similar to the simple “one set of conditions” Ideal Gas Law problems we saw before. You are given values for all the variables in Dalton’s Law but one and are asked the value of the one you are not given. The solution uses the same approach: solve the equation for the unknown quantity, substitute in the values of the variables you know, and compute the answer.

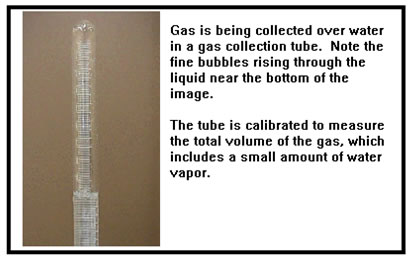

Another common situation that requires Dalton’s Law is shown in Example 36b of you workbook. A sample of gas – in this case oxygen – is collected over water. The gas actually contains a mixture of oxygen gas and water vapor. We can easily measure the total volume and total pressure of the mixture, but since we are interested in the oxygen, for pressure what we really want to know is the partial pressure of the oxygen alone.

Collecting gas over a liquid is a convenient way to collect the gas without mixing it with air. A container is filled with liquid, often water, and turned upside down. Then, the gas to be collected is allowed to bubble up through the liquid and displaces it at the top of the container, where no air can get in. The only disadvantage is that there will be a small amount of evaporated liquid mixed in with the gas. If the liquid is water, the amount of water vapor is small but significant – about 3.5% of the total. If the liquid is mercury, the amount of mercury vapor is practically zero. (Of course, there are other practical concerns about using mercury as the liquid, not the least of which is its toxicity and difficulty in disposing of it in an environmentally conscious manner.) |

|

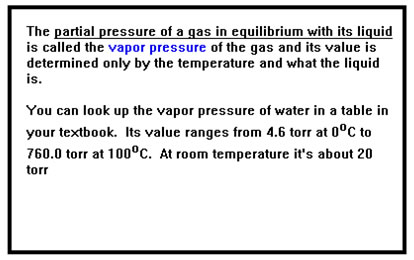

Because the water vapor present is in equilibrium with liquid water, the partial pressure of the water vapor is fixed and depends only on the temperature. We can look up its value in tables found in reference books and textbooks (and on the internet, though you must consider the source before placing confidence in values found online). At 27 oC, the vapor pressure of water is 26.7 torr. The water vapor evaporates from and recondenses onto the surface of the water. The rate of evaporation is determined by the temperature while the rate of condensation is determined by the partial pressure of the water vapor. The vapor pressure of the water is the partial pressure that makes the rate of condensation equal to the rate of evaporation. It will be different for each value of the temperature. |

|

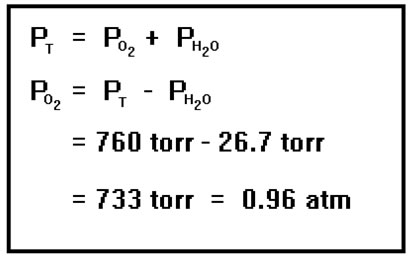

The total pressure is 760 torr, and since this is the sum of the partial pressure of the water vapor (26.7 torr) and the partial pressure of the oxygen, the oxygen’s partial pressure must be the difference between the total pressure and the partial pressure of the water vapor, 733 torr. Remember the manometers? If the level inside the vessel that contains the gas is the same as the level of the liquid outside, then the pressure inside and the pressure outside will be the same, about one atmosphere. (We can measure it exactly with a barometer.) For this reason, before you read the volume of a gas inside a gas collection tube, make sure that the water levels inside and outside the tube are the same. This way, it’s easy to determine the total pressure inside the tube. |

|

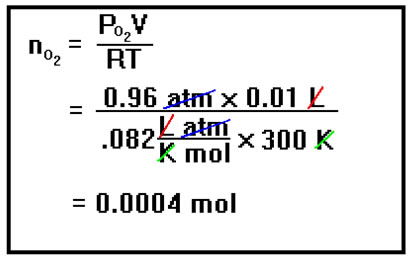

The number of moles of oxygen can now be calculated from the Ideal Gas Law using the partial pressure of the oxygen and the volume and the temperature given in the problem. Recall that the Ideal Gas Law applies separately to each gas in a mixture. As long as we are careful to use the pressure due to the oxygen alone, the Ideal Gas Law will give us the number of moles of oxygen alone. If you used the total pressure in the tube, the n that you calculate would be the number of moles of oxygen and water vapor combined. |

|

Exercise 37 in your workbook contains some practice problems involving Dalton’s Law for you to try. You will find the answers below. In the first of these problems, 37a, the “pressure of the collected gas is 740 torr.” This is the total pressure of the hydrogen and water vapor together. To solve this problem, you will need to look up the vapor pressure of water at 25 oC. You can look it up in one of the reference books in the lab, or look here. (You do have a question in your problem set for which you should look up the vapor pressure of water in the lab reference books. The vapor pressure tables in the "CRC Handbook for Chemistry and Physics" reference books have more data for temperatures measured to tenths of degrees, which is what you'll need for the problem set question.)

Answers to Exercise 37:

a. 716 torr

b. 13 torr or 0.017 atm

Lab Work

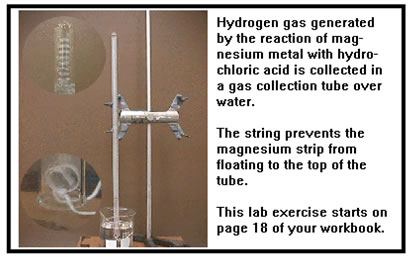

The laboratory exercise for this lesson involves measuring the gas constant, R. In this exercise you will collect hydrogen gas over water, so you will need to use Dalton’s Law to determine the partial pressure of hydrogen. Complete instructions are included in your workbook.

This experiment can give quite accurate results if done carefully. Be sure to follow the procedures exactly. Some common sources of error include failing to clean the magnesium ribbon thoroughly, allowing air to enter the gas collection tube or allowing hydrogen to escape, and not waiting long enough for the temperature of the gases inside the tube to come to room temperature.

Also, remember that you will calculate n from the mass of magnesium you used, not from the Ideal Gas Law. If you use the Ideal Gas Law to determine n, you will essentially have used R to determine R … but then you won’t have an “experimentally” determined R since you used the known (accepted) value in your calculations.

You will type a lab report about this experiment; if you need to review the lab report format, check with your instructor.

Also, be sure to complete and turn in the problem set for this lesson. You should also try the self quiz. You will find the answers for the self quiz on the Wrap Up page of this lesson.