Lesson 1: n, V, T, & P

moles (n) | volume (V) | temperature (T) | pressure (P) | density (D)

moles (n)

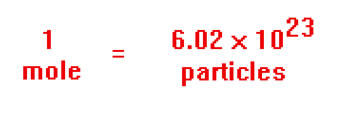

In the past, we have measured amounts of materials using mass. Many of the properties of an ideal gas, however, are determined by the number of gas particles present, not their mass; it makes more sense to use the number of moles to measure the amount of gas present since the number of moles measures the number of particles directly.

Recall that one more of a chemical substance contains 6.02 x 1023 atoms (or molecules) and its mass is just its atomic (or molecular) weight in grams.

If you know the number of moles of something you have, you know how many of them there are, even if you don’t know WHAT they are. For this reason, we can use moles of gas particles instead of the actual number of gas particles when we are dealing with the properties of gases.

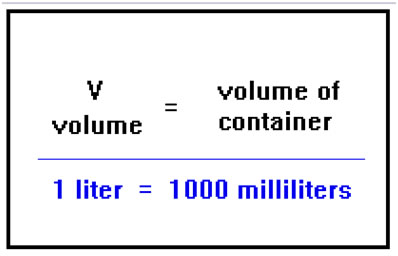

volume (V)

Because the particles travel independently of one another, they will occupy the entire volume of whatever container they are in. Therefore, the volume of a gas is actually nothing more than the volume of its container. This volume, of course, is mostly empty space. Volumes of gases are usually measure in liters (L) or milliliters (mL).

Other units of volume you might encounter are cm3 and cc’s (cubic centimeters), which are the same as mL. These are the most common units used in chemistry. It is a simple matter to convert between these and English units such as ounces, quarts, gallons, and so on, using conversion factors found in standard tables. If you need to, you can review the relevant lessons from Chemistry 104.

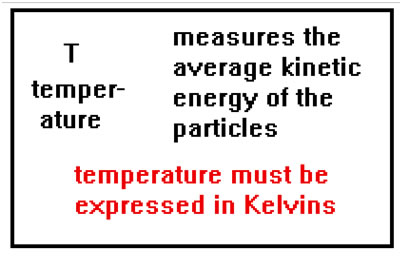

temperature (T)

Temperature is a measure of the average energy of motion – the kinetic energy – of atoms and molecules. Since this energy determines the force with which they strike the walls of their container, the properties of gases depend on their temperature. Temperature must be measured in Kelvins rather than the usual degrees Celsius. We’ll discuss why this is, and how to convert between the various temperature units, in the section on “Gas Laws.”

|

Temperature is a measure of the “concentration” of the heat (energy) in a substance and it is related to the average kinetic energy of the molecules. Heat would be the total amount of kinetic energy rather than the average. Kinetic energy is determined by both the speed of motion of a particle and its mass. If two particles have the same kinetic energy but different masses, the lighter particle must be traveling more rapidly than the heavier particle in order to have the same energy. |

pressure (P)

The pressure exerted by a gas is the force per unit area it exerts on the walls of its container. For example, we measure the pressure of the air in a tire in units that reflect this: psi, or pounds per square inch.

On the scale of ordinary objects, gravity has no effect on the particles of a gas, so that they tend to strike the top, sides, and bottom of their container all with the same average force. Therefore the pressure inside an ordinary size container is the same everywhere. If you had a container that was a container that was a thousand feet high, however, the effect of gravity would be noticeable and the pressure would be slightly higher at the bottom of the container. To make a really significant difference, the container would have to be about a mile or more high.

Measuring Pressure:

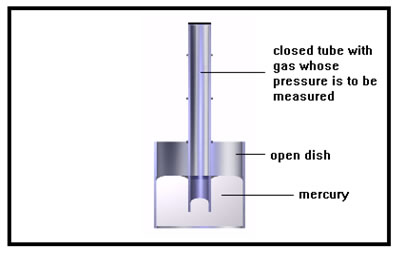

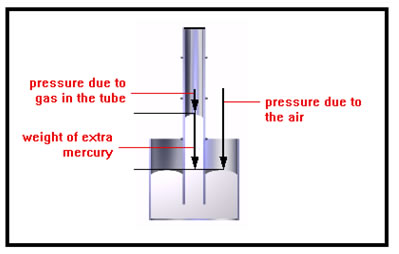

The drawing to the right shows a manometer, a simple device for measuring the pressure of a gas. The dish and tube are filled with a liquid, usually mercury, and the gas whose pressure we want to measure is inside the tube. This gas exerts pressure on the end of the mercury column inside the tube. In an actual manometer, there would be a valve for filling and emptying the tube with gas – the diagram is only a schematic to show how the device works. (Example 4 in your workbook shows another type of manometer, a J-tube manometer.) |

|

Mercury is often used because it is a very heavy liquid and does not evaporate easily. We will see what difference this makes shortly.

Like many pressure measuring devices, the manometer actually measures the difference between two pressures, that of the gas inside the tube and that of the air outside of the bulb.

It may not be obvious, but the diameter of the tube containing the mercury has no effect on the height of the mercury column. If we made the tube larger, the column of mercury would, indeed, be heavier, but because pressure is a force per unit area and the area of the mercury exposed to the gas would be greater, the total force of the gas pressing on the mercury would be greater as well and the height of the mercury column would remain just the same.

The open dish is exposed to the air, which is pushing on the surface of the mercury in the dish. Because the pressure of the gas inside the tube is greater, it pushes the mercury column down until the weight of the extra mercury in the dish plus the pressure of the air just equals the pressure of the gas inside the tube. |

|

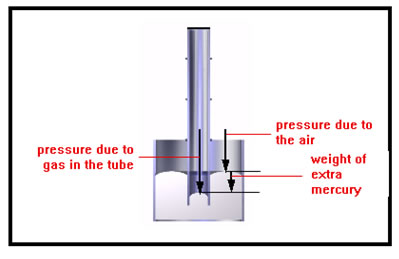

In this drawing, the pressure inside and the pressure outside are just equal, so the mercury levels are the same. Both the gas inside the tube and the outside air are pressing on the mercury with the same force per unit area, so the level of the mercury in the two sides of the tube are the same. The slightly curved surface of the mercury at the top is called the meniscus. Water has a meniscus that curves downward, but mercury has a meniscus that curves upward. |

|

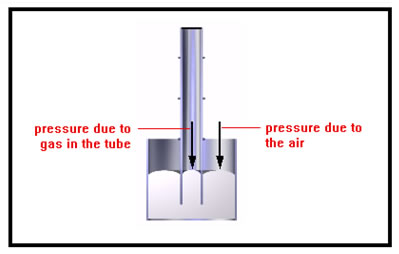

In this drawing, the pressure inside the tube is less than the pressure outside, so the mercury exposed to the air is pushed down until the weight of the extra mercury in the inside portion of the tube plus the pressure of the gas in the bulb just balance the external pressure. Strictly speaking, it is not the weight of the extra mercury that equals the difference in the two pressures, it is the weight of the mercury per unit area that is equal to the difference in pressures. This is because pressure is a force per unit area. |

|

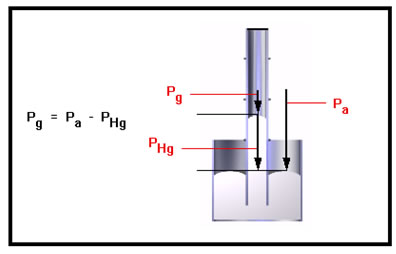

To compute the pressure of the gas in the tube, we subtract the weight (per square inch) of the extra mercury in the tube from atmospheric pressure. In the first illustration you saw, we would need to add the weight (per square inch) of the extra mercury to the pressure of the atmosphere. |

|

Atmospheric Pressure:

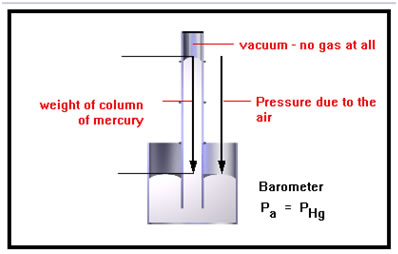

This device works just like the manometers you saw before, but there is no gas in the small volume in the tube above the mercury. In other words, there is no pressure being exerted on the top of the mercury column, so the weight (per square inch) of the column of mercury is just equal to the pressure exerted by the air. This device is called a barometer.

It’s not quite true that there is no gas in the top of the tube. A small amount of the mercury evaporates and this mercury vapor exerts a pressure on the top of the column of liquid. One of the reasons that mercury is used in these devices is that very little of it evaporates at ordinary temperatures and so the pressure exerted at the top of the column is very small – so small, in fact, that the error introduced is on the order of only 0.0002 percent.

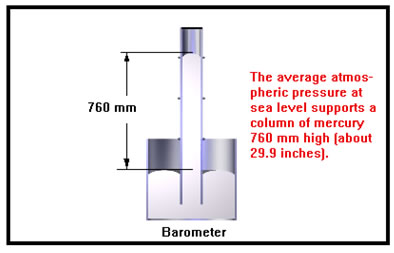

Manometers and barometers are the most accurate simple way we have to measure pressure. Because of this pressure is often specified by the height of a column of mercury it will support, usually in millimeters. This unit, mmHg (millimeters of mercury), has been given the name “torr.” The other major reason for using mercury is that it is very dense and a column of it heavy enough to balance the pressure of the atmosphere is only about 30 inches high. If we used water, for example, the column would have to be over 400 inches high and barometers would be quite unwieldy. |

|

The torr is named after Evangelista Torricelli, an Italian physicist. |

|

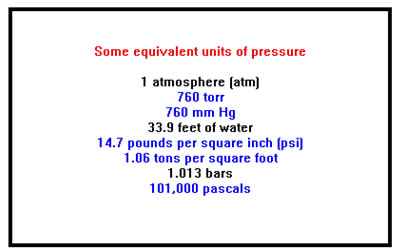

Another unit of pressure that is frequently used is the “atmosphere.” One atmosphere (1 atm) is about what normal air pressure is at sea level. Since this varies a bit with the weather, it has been defined precisely as 760 torr. The equivalent value in pounds per square inch is about 14.7 psi.

In the U.S., pressure is sometimes measured in inches of mercury instead of millimeters. You will encounter this unit most often in weather reports.

There are several other units of pressure that you are less likely to encounter – the bar and the pascal are two.

In this course, we will restrict ourselves for the most part to using just mmHg, torr, and atmospheres; you should memorize the relationships between those three units and be able to convert between them.

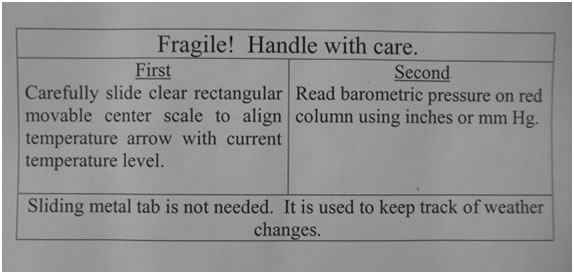

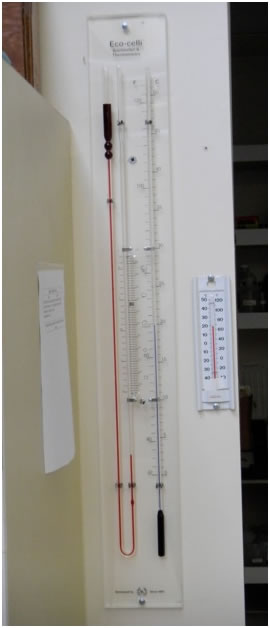

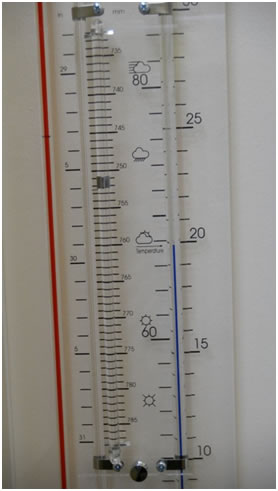

When you visit the lab to do your lab assignment for this lesson, examine the barometer there and practice taking a reading on it. Record your reading in your workbook (Ex. 6) and check it with the instructor. The barometer is located on the wall on the left side of the room as you walk in to the left of the door next to the blackboard.

|

|

|

|

||

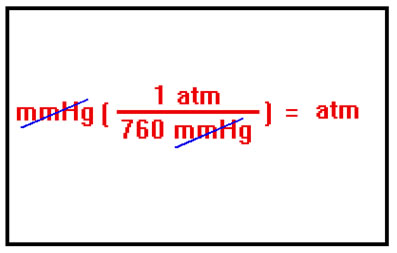

Converting Between Pressure Units:

It will sometimes be necessary to convert from one set of pressure units to another. This is done using the same, simple conversion factor method you use to convert between units of mass or length. Recall that: |

|

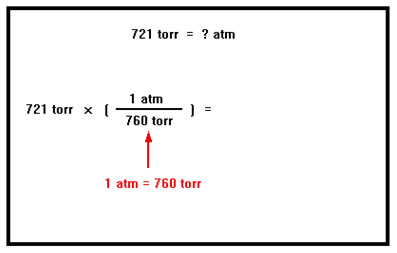

For example, to convert 721 torr to atm, we construct a conversion factor with 760 torr in the denominator and 1 atm in the numerator. Recall that torr is just another name for mmHg. The numbers 1 atm and 760 torr are defined numbers and so do not limit the precision of the conversion. The answer will have three significant digits. |

|

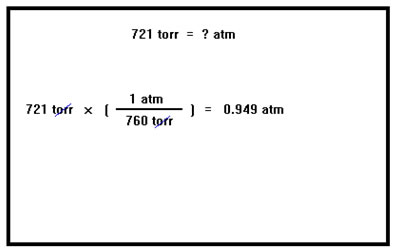

Carrying out the multiplication and division gives us 0.949 atm. Other conversions are done in the same way. As you might suspect, converting between inches of mercury and millimeters of mercury is done using the conversion factor between inches and millimeters: 1 inch = 25.4 mm |

|

Here’s a problem to try on your own.

The air pressure in an automobile tire is found to be 36.2 psi. What is this pressure in torr? (1 atm = 760 torr = 14.7 psi).

You will need to multiply 36.7 psi by a conversion factor that changes psi to torr. That factor should have units of psi on the bottom and units of torr on the top. The numbers that go into the conversion factor are the numbers of psi and torr that are the same pressure: 14.7 psi and 760 torr.

While 760 torr is a defined number, 14.7 psi is not, and so has only three significant digits.

You should find that the answer is 1870 torr, or 1.87 x 103 torr.

To get some practice doing these kinds of pressure conversion problems, try those in Exercise 8 in your workbook. The problems in Exercise 8 are very similar to those you just saw. In each case, you can construct a single conversion factor that relates the original units to those you are trying to convert to. You may, if you choose, do some of the conversions in two steps if you find that easier. For example, in the last problem of Ex. 8, you might convert inches of mercury to mmHg, then convert mmHg to atm. To check your work, you can find the answers below.

Exercise 8 answers:

a. 0.395 atm

b. 400 torr

c. 844 torr

d. 0.997 atm

e. 0.983 atm

Density of Gases:

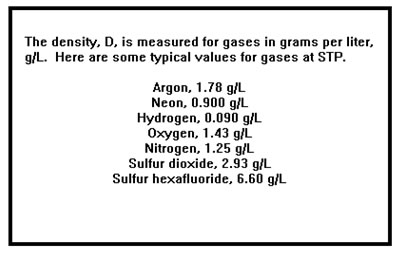

One more measurement that we will use occasionally in this lesson on gases is density, D. It is one you are already familiar with, the mass divided by the volume. Because gases are so much lighter than liquids and solids, however, the unit usually used for the density of gases is grams per liter, g/L, rather than grams per milliliter.

We will eventually use measurements of the density of a gas to compute its molecular weight, both of which are properties of a gas that depend on what the gas is.

It should make sense that density can be used to find molecular weight, since the specific property of the gas they both depend on is its mass: density relates mass to volume, and molecular weight relates mass to number of moles.

In the next section, "Gas Laws," we'll look at how the properties of gases are related to and affect each other.