Lesson 1: Gas Laws

In this section, we'll examine how n, V, T, and P are related to each other and how they affect each other. These gas laws will form the basis for the Ideal Gas Law, which we'll study in the next section.

P & n | Boyle's Law (P & V) | P & T | Avogadro's Law (n & V) | Charles' Law (V & T) | Why use Kelvins for T?

P & n

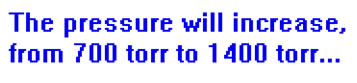

Imagine a container of fixed volume and insulated so that the temperature inside stays constant. Imagine it contains 2 moles of gas and the pressure is 700 torr. What do you think would happen to the pressure if we added another 2 moles of gas?

Since pressure is due to collisions with the walls of the container, you should think about how doubling the number of gas particles from 2 to 4 moles will affect the number and force of the collisions in the container. How will doubling the number of gas particles change the number of collisions that occur each second? How will doubling the number of gas particles change the force with which the average particle collides with the wall?

The Kinetic Molecular Theory (KMT) says that the pressure is due to collisions with the walls of the container and depends on how many gas particles there are and how violent the collisions are. Since the energy depends only on the temperature, which doesn’t change, the collisions won’t be harder but adding gas will increase the number of collisions, thus increasing the pressure.

Doubling the number of gas particles has no effect on how hard they strike the walls of the container. That force is determined by the velocity and mass of the particles. Their mass obviously doesn’t change, and their velocity depends on the temperature, which does not change in this example either, so the force of the average collision will remain the same.

Doubling the number of gas particles does exactly double the number of times each second a particle strikes the wall of the container. Thus the pressure doubles as well. |

|

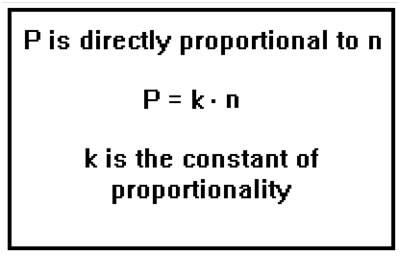

For an ideal gas, the pressure is directly proportional to the number of moles of gas present. In mathematical symbols, we say that P is equal to a constant times n. The value of the constant depends on the volume and the temperature. |

|

The fact that P and n are directly proportional means not just that when n increases so does P, it means that when n is doubled, so is P; when n is tripled, so is P; when n is cut by one fourth, so is P. In general, when n increases or decreases, the ratio of the new to the old values of n will be the same as the ratio of the new to the old values of P. The value of the constant k determines how large P is compared to n, but no matter what value k has, large or small, the correspondence between the ratio of the change in n and the ratio of the change in P will exist.

Boyle's Law (P & V)

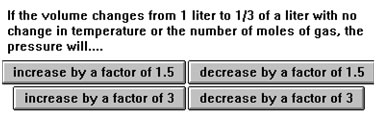

Now imagine a container whose volume can change. Suppose such a container has a volume of one liter and, without changing the amount of gas it contains or its temperature, we decrease its volume to 1/3 of a liter. What will happen to the pressure?

Again, consider how the number of collisions and the force of the average collision will be affected. Here’s a hint: although the number of gas particles has not changed, the total volume of their container has decreased, so each particle has less room to move around in. As before, since we have not changed the temperature, the force of the average collision will not change.

Again, because the temperature has not changed, the collisions will be no more or less violent, but the number of collisions will change. In one third the volume, each gas particle has, on the average, one third the distance to go before hitting the wall of the container, and will therefore do so three times as often, increasing the pressure by a factor of three.

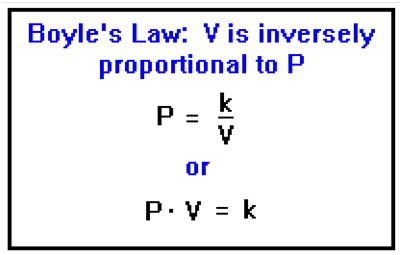

For an ideal gas, the pressure is inversely proportional to the volume of the container. Mathematically, we can express this by saying that the pressure is equal to a constant times one over the volume or that the pressure times the volume equals a constant. This time, the value of the constant depends on the temperature and the number of moles. This relationship is known as Boyle’s Law. |

|

Inverse proportionality works the same way that direct proportionality does, except that when two quantities are inversely proportional, when one goes up, the other goes down. The correspondence between ratios remains. When one goes up by a factor of two, the other goes down by a factor of two, and so on. Again, the constant determines the relative size of the two quantities. If the constant is close to 1, they will be close to the same size. If the constant is very large or very small, one will be much larger or much smaller than the other.

You can experience this relationship yourself in the lab. In the area labeled Exercise 9 you will find a syringe filled with a gas. The opening has been closed off so that you can change the volume of the syringe without changing the amount of gas present. When you start, the pressure inside the syringe is the same as the pressure outside the syringe. See what happens as you decrease and increase the volume occupied by the gas inside the syringe. |

|

The pressure of the surrounding air does not seem like much. To get an idea of how strong it is, see how much work it takes to cut the volume of the syringe in half and hold it there. If you cut the volume of the syringe in half, you will double the pressure inside and the additional pressure you will be working against will be the difference between the pressure inside the syringe (2 atm) and outside the syringe (1 atm): just about one atmosphere.

If you increase the volume of the syringe by a factor of two, the pressure inside the syringe will drop to 0.5 atmosphere and the difference you will be working against will be only 0.5 atmosphere. See if it feels to you like it’s twice as hard to cut the volume of the syringe in half as it is to double its volume.

P & T

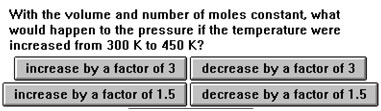

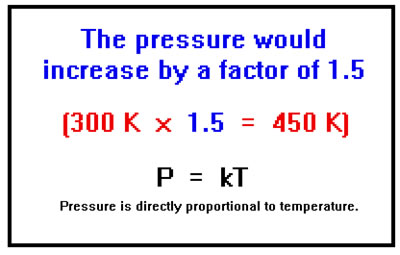

Imagine, now, that you have a closed container – the number of moles of gas doesn’t change, whose volume also does not change. What would happen to the pressure if you increased the temperature from 300 K to 450 K?

In this case, the number of gas particles and the volume that they occupy does not change.

Since the temperature does change, so does their speed. How would this affect the force of the average collision of a gas particle with the wall of the container? Would it also affect the number of collisions that occur each second?

Here, the collisions would become more violent and they would also become more frequent, in both cases because the gas particles would be moving more rapidly. It turns out that, as long as the temperature is expressed in Kelvins, the pressure is proportional to the temperature and since the temperature increased by a factor of 1.5, so would the pressure. It is not obvious why, if both the force of the collisions and their frequency increase, the increase in pressure would be proportional to the temperature.

A detailed discussion is beyond us here, but it does make sense in a way if you consider that both the pressure and the temperature are sensitive to the same thing: the amount of kinetic energy the atoms/molecules have as a result of their motion. When the temperature of a substance increases, it feels hotter to you because the molecules are hitting your skin both harder and more frequently, the same two factors that cause the pressure to increase.

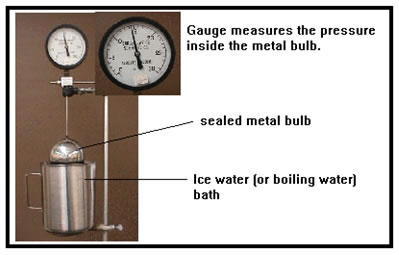

Exercise 10 in the lab will give you an opportunity to verify this for yourself. First note the pressure on the gauge, then dip the metal globe into ice water, then boiling water and note how the pressure changes. Enter the temperature and pressure values into the first two lines of Exercise 10 in your workbook. The gauge attached to the top of the metal globe is rather heavy. If you let go while the globe is in the liquid, the whole set-up will tip over. It will take a few minutes for all the gas inside the globe to come to the temperature of the water bath. Be patient and wait for the pressure gauge to stop changing. It will change rather slowly toward the end. |

|

Avogadro's Law (n & V)

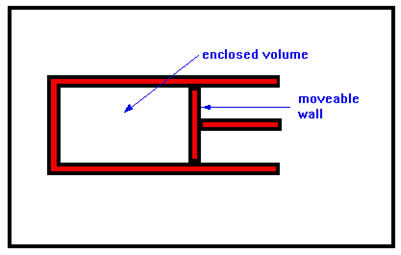

|

This drawing shows a constant pressure container. The wall on the right is moveable – like a piston. It will stay put as long as the pressures inside and outside the container are the same. If the pressure inside increases, the wall will begin to move out and the resulting increase in volume will lower the pressure inside the container. This will continue until the pressures inside and outside are once more equal. |

The syringe you used earlier in this section is just such a container. If the plunger of the syringe is allowed to move freely, the pressure inside the syringe will always be exactly the same as the pressure outside. Any difference would cause the plunger to move in or out until the pressures were once again equal.

This, of course, assumes that there is no leakage past the seal between the moveable wall and the interior wall of the container. As you noted when you worked with the syringe, the seal in that case was pretty good.

Suppose that we take such a container and increase the number of moles of gas it contains from 1 mole to 2 moles. What will happen to the volume?

This is similar to the example in which we added gas to a container at constant volume and found that the pressure increased. Here, the volume will change in response to any change in pressure until the pressure returns to its original value. How must the volume change if we are to preserve the pressure unchanged?

Increasing the number of moles of gas would cause the pressure inside the container to increase. This would, in turn, move the piston out. To compensate for doubling the number of moles of gas, the container’s volume will have to increase by a factor of two. (In fact, the pressure will increase only enough to overcome the friction between the moveable wall and the interior walls of the container. Still, we can predict the final state of affairs by imagining that first the pressure increases to its maximum, then the container expands to return the pressure to its original value. Since we double the number of moles of gas, the pressure would double. Then, to put the pressure back in half, the volume would have to double.)

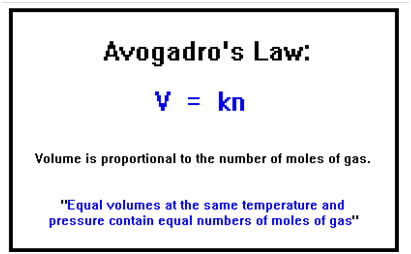

The volume of an ideal gas is proportional to the number of moles of gas. Mathematically, V equals a constant times n. This is sometimes known as Avogadro’s Law. This was a particularly important discovery, for it gas chemists their first means of measuring the number of atoms (or molecules) in a sample of material. Although they could not yet say exactly how many that was, they were able to measure relative amounts of atoms and molecules: how many were in this sample compared to how many were in that. |

|

Charles' Law (V & T)

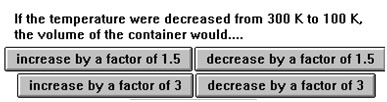

Now imagine our container with its original one mole of gas and suppose that we decrease the temperature from 300 to 100 K. Now what happens to the volume of the container?

Again, take the problem in two steps. First, let the pressure change according to how the temperature changes, then figure out what volume change would have to occur for the pressure to return to its original value.

Since decreasing the temperature by a factor of three would decrease the pressure by the same factor, the volume will also decrease by a factor of three in order to maintain equal pressures inside and outside the container.

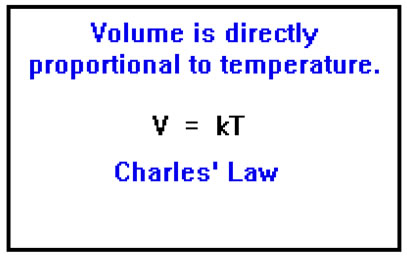

The volume of an ideal gas is proportional to it temperature. Mathematically, V=kT. This is known as Charles’ Law. |

|

Avogadro’s Law said that the volume was directly proportional to the number of moles of gas and the constant of proportionality – let’s call it k’ – depended on the temperature and the pressure: V=k’n.

Now Charles’ Law says that volume is directly proportional to temperature and the constant of proportionality – let’s call this one k” – depends on number of moles and pressure: V=k”T.

We can combine these two laws by saying that volume is proportional to both temperature and number of moles – and the constant, which we’ll call k, now depends only on the pressure: V=knT.

In the next section of the lesson, "The Ideal Gas Law," we'll see how we can combine all three gas laws to create one general law to describe the behaviors of ideal gases.

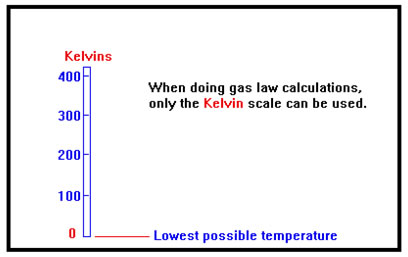

Why use Kelvins for T?

You might be wondering why temperatures must always be expressed in Kelvins when working with ideal gases, but we can use many different units of pressure (torr, atm, psi, etc.) or volume (mL, L, gallons, and so on).

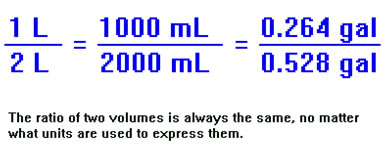

Volume, for example, is always inversely proportional to pressure, no matter what units of pressure and volume are used. Changing the units does change the value of the constant of proportionality, but the relationship PV=k still holds.

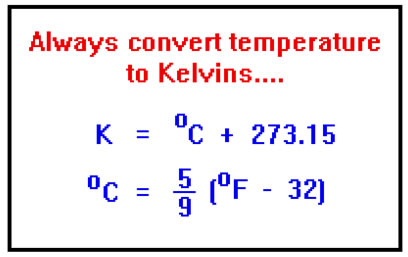

For temperature, V=kT is only true when the temperature is expressed in Kelvins. There is a relationship between volume and temperature in degrees Celsius, but the two are not directly proportional. The actual relationship is: V=k(T+273.15)

Suppose we increase, say, a volume from 1 liter to 2 liters, doubling the value. In milliliters, the volume went up from 1000 mL to 2000 mL, it doubled. In gallons, the volume went from 0.264 gal to 0.528 gal – it doubled. No matter what units we use, the volume doubles. This is true because converting from one set of volume units to another always involves multiplying by some conversion factor. If you multiply a doubled volume by a conversion factor, you get a doubled answer. This is true of pressure as well. |

|

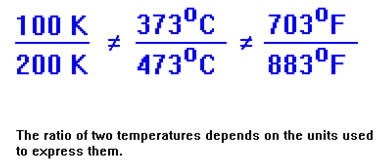

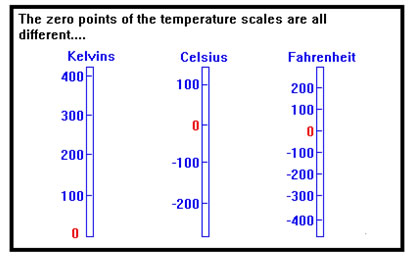

Now let’s try temperature. Doubling 100K gives us 200K. But in degrees Celsius, the temperature went from 373 to 473, and the ratio is only 1:1.27 not double. In degrees Fahrenheit, the temperature changed from 703 to 883, a ratio of 1:1.26. So, unlike converting volumes or pressures, to convert from one temperature to another, you may or may not have to multiply, but you always have to add a constant: K = oC + 273.15 Doubling the temperature in oC does not double the temperature in oF or K. |

|

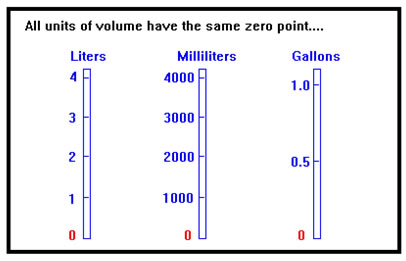

In dealing with volume, the zero point is defined naturally as “no volume at all,” and this is the same no matter what units of volume we use, so that 0 liters and 0 gallons (and 0 cubic feet and 0 of any other unit of volume) all refer to the same thing. In other words, the only difference between units of volume, (and pressure, mass, force, energy, density, speed, and almost any other property of physical objects you can think of) is their size. They all have the same starting point; that is, they all have the same definition of zero. |

|

But 0 oC is arbitrarily defined as the freezing point of water, which is 32 oF and also corresponds to 273.15 K, so the zero points of the temperature scales are not all the same. The reason that the Celsius scale was based on the freezing and boiling points of pure water (0 oC and 100 oC, respectively) was that these were easy to reproduce in any laboratory. That meant that temperatures measured in one laboratory could be accurately compared with temperatures measured in any other. |

|

In fact, only the Kelvin scale assigns 0 to its “natural” value: the lowest possible temperature, the absence of all heat. For this reason, only the Kelvin scale can be used for calculations involving gases. When the temperature scales were first developed, the idea of a lowest possible temperature had not yet occurred to anyone. The zero points were defined from convenience rather than from any understanding of what temperature corresponded to physically. For convenience, the Kelvin scale was designed to have graduations the same size as degrees Celsius (that’s why you don’t have to multiply when converting), but the zero point was changed to the lowest possible temperature – the point where all molecular (or atomic) motion stops, or the absence of all kinetic energy. |

The website "Physics 2000" has a great interactive animation about gas particles and Kelvin temperatures. I recommend following the link and taking a peek! |

Here are some temperature conversion problems for you to try. If you need help, be sure to contact your instructor.

The formula for converting between Kelvins and oC is: K = oC + 273.15. For convenience, we usually ignore the .15 and just use the 273. This is generally precise enough for our purposes. By the way, have you noticed that we refer to "degrees Celsius" and "degrees Fahrenheit" but not "degrees" Kelvin? The temperature unit K is correctly written without the degree sign and is referred to as "Kelvins" (not "degrees Kelvin").

1. Convert 34 oC to Kelvins.

2. Now convert 34 oF to Kelvins. (You will need to convert from oF to oC first, using the formula: oC = 5/9 x (oF – 32). Then use the formula to convert from oC to K. You do not need to memorize the conversion between oF to oC, but you should memorize the conversion for oC to K.)

You should have determined the answers to be 307 K and 274 K, respectively. There are some more temperature conversion practice problems in Example 21 in your workbook. You can check your answers below.

answers to Example 21:

a. 273K 298 K 373 K 243 K 115 K

b. -273 oC -248 oC -93 oC 25 oC 77 oC