Lesson 1: The Ideal Gas Law

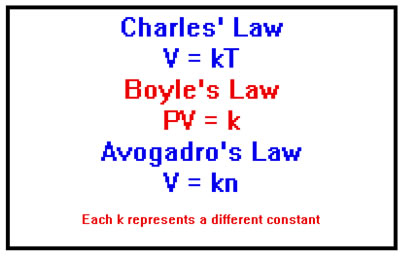

In the last section we saw that Charles’ Law relates the volume of a gas to its temperature; Boyle’s Law relates volume to pressure; and Avogadro’s Law relates volume to the number of moles of gas present, as well as a number of other relationships between P, V, n, and T.

In particular, we saw that volume is directly proportional to the temperature (in Kelvins!) and the number of moles of gas, and inversely proportional to pressure. In each case, there was a constant of proportionality whose value depending on the values of the quantities that were being held constant.

Rather than remember all of the possible relationships between P, V, n, and T, and have to deal with a host of different “constants,” it would be nice to have a single relationship with a constant of proportionality that was really constant; that is, one whose value did not depend on what the other parameters’ values were.

The Ideal Gas Law | Using the Ideal Gas Law

The Ideal Gas Law

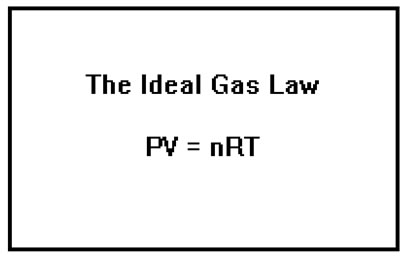

All of these relationships can be combined into a single law called the “Ideal Gas Law.” This law, which applies to gases whose behavior follows the assumptions of the kinetic molecular theory, relates pressure, volume, temperature, and number of moles of gas by the equation PV = nRT.

The Ideal Gas Law can easily be reduced to Charles’, Boyle’s, or Avogadro’s Law. For example, suppose that n and T are held constant. Then the product nRT is also a constant and we can give it the name, k. The Ideal Gas Law then becomes PV=k, which is just Boyle’s Law.

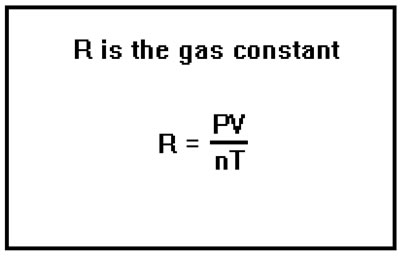

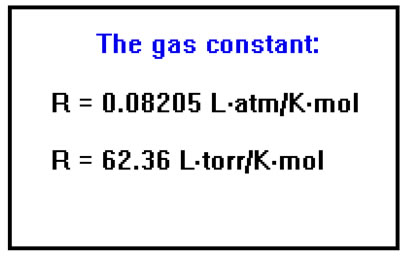

The symbol “R” in this equation is a constant called “the gas constant” and its value can be computed by measuring the temperature, volume, and pressure of a known quantity of an ideal gas and substituting these values into the Ideal Gas Law solved for R. In fact, this is the bases of the laboratory exercise for this lesson. In it, you will measure n, T, P, and V for a sample of hydrogen gas, then use these values to compute the value of the gas constant, R. The actual value of R will depend on the units that you use for P and V (n is always in moles and T in Kelvins). In practice, the units of V are almost always liters, while P is most often either in torr or in atmospheres. |

|

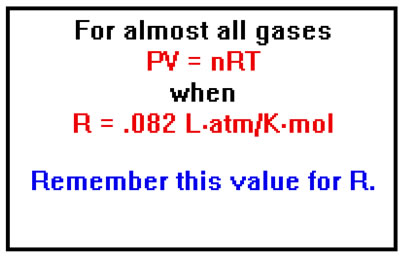

If P is measured in atmospheres, V in liters, and T in Kelvins, the value of the gas constant is found to be 0.08205 Latm/Kmole. If pressure is measured in torr, the value of R is 62.36 Ltorr/Kmol. It is not uncommon for important physical constants to have complex units like this. As you will see, the units in the constant will cancel units in P, V, n, and/or T so that the answer to any particular calculation will match the units you expect for the answer – provided, of course, that the problem has been solved correctly. |

|

While, strictly speaking, the Ideal Gas Law applies only to ideal gases, it works well enough for almost all gases if we use a less precise value for R: 0.082 Latm/Kmol.

This means that most gases behave ideally to about two significant digits. In practice, gases whose behavior deviates from the ideal gas law by more than about 1% are typically those with large, multi-atom molecules (say, ten atoms or more) or medium-sized molecules capable of hydrogen bonding. All of the gases we will deal with in this lesson obey the ideal gas law with errors no larger than about 1% and in most cases much less than this.

Using the Ideal Gas Law

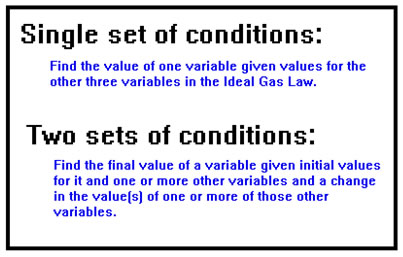

The two most common problems you will be asked to solve using the Ideal Gas Law are problems involving a single set of conditions and problems involving a set of initial conditions and a change in one or more of the variables.

An example of a problem of the first type might be: “What is the pressure of an ideal gas if 2.5 mol occupy a volume of 15.0 L at a temperature of 25 oC?” An example of the second type of problem might be: “A sample of gas exerts a pressure of 1.0 atm at a temperature of 250 K in a 250 mL container. What will the pressure become if the gas is heated to 350 K and the volume is increased to 500 mL?” |

|

Using the Ideal Gas Law: One Set of Conditions

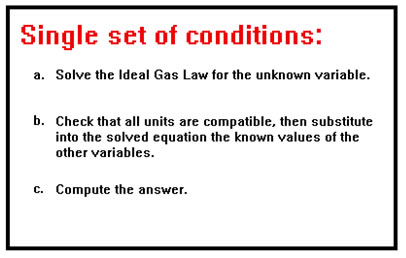

For problems of the first type, all you need to do is to solve the Ideal Gas Law for the variable whose value you are trying to find, then substitute values for the other known variables and compute the answer.

|

This will require a bit of simple algebra. If you’re a little rusty, it might be a good idea to review the techniques used to solve simple algebraic equations. The two operations you will most often use are multiplying both sides of an equation by some quantity and dividing both sides of an equation by some quantity in order to solve it. At times you may also need to add or subtract quantities from both sides of an equation. |

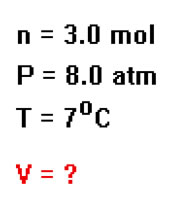

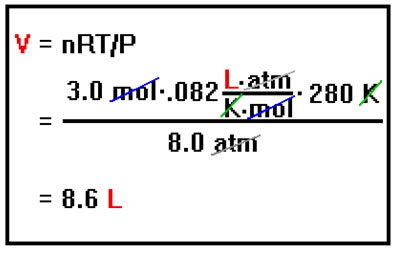

Here is an example: What is the volume of 3.0 mole of gas at a pressure of 8.0 atm and a temperature of 7 oC? In this problem you are given n, P, and T and asked for the value of V. Hopefully you have already memorized the value of R: R= 0.082 Latm/Kmol. |

|

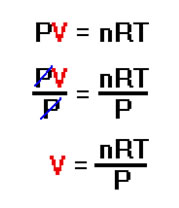

First, solving the ideal gas law for V involves a little basic algebra. Simply divide both sides by P and the equation becomes V = nRT/P. You know to divide both sides by P because you want to isolate V on one side of the equation (solve for V). Dividing through by P will cancel P on the left, leaving V by itself. |

|

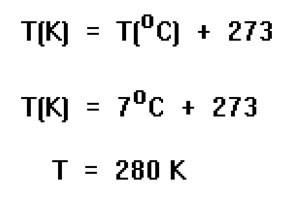

Before substituting in the values of n, T, and P, we must change the units of temperature to Kelvins. P and n are already in the right units: atmospheres and moles, respectively. The appropriate units will be determined by the units of the gas constant, R. Since we use the value (0.082) for this constant in Latm/Kmol, we will need to express the pressure in atmospheres, the temperature in Kelvins, and the amount of gas in moles. Our answer will be in units of liters because those are the volume units for this value of the gas constant. |

|

Now, substituting the values of n, R, T, and P into the solved equation, we find that the volume is 8.6 liters. Note how the units cancel to give the units of the answer, liters. Checking to make sure that the units cancel properly to give the appropriate units for the answer (in this case, liters for a volume) is a good way to check that you’ve done the algebra correctly and a valuable habit to get into. Always include the units in your calculations so that you can easily perform this check. |

|

You will find a similar problem worked out for you in Example 27b of your workbook. Be sure you understand these examples before you move on.

Also, be sure to pay attention to the number of significant digits. Since the value of R that we use has only two significant digits, your answers, in general, will have only two. This is consistent with our assumption that the real gases we are dealing with obey the ideal gas law to within about 1%. If you have reason to use a more precise value for R, its value to four significant digits is R=0.08205 Latm/Kmol.

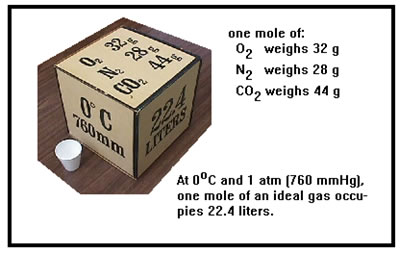

The phrase “standard temperature and pressure,” often abbreviated STP, is a shorthand way of referring to a pressure of one atmosphere (1 atm, or 760 torr) and a temperature of 0 oC (273 K). You should remember this phrase and what it means. It is often useful to compare the properties of two or more gases. Because gases are sensitive to changes in temperature and pressure, they must always be compared at the same values of T and P. Establishing “standard” values for these two variables therefore makes it easier to compare gases. |

|

Exercise 28 in your workbook contains three practice problems of this same type for you to work out. Take some time now to do these problems. You’ll find the answers below.

For all the practice problems, an answer to two significant digits will suffice, though you could get the answer to problem b. to three significant digits and the answer to problem c. to more than that if you wanted to.

Answers to Exercise 28:

a. 48 atm

b. 249 K or -24 oC

c. 22.4 L

Using the Ideal Gas Law: Two Sets of Conditions

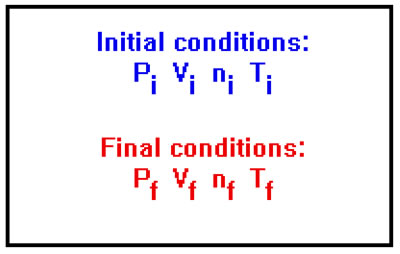

Another common type of problem involves two sets of conditions: an initial set of values for P, V, n, and T, and a change in one or more of them to give a final set of values, one of which you are asked to calculate.

You will often find in this type of problem, that one or more of the variables are ignored. This doesn’t prevent you from working the problem as long as you assume that the values of variables for which no information is given do not change.

For example, the sample of this type of problem you saw stated that “A sample of gas occupies 250.0 mL at a pressure of 1.0 atm and a temperature of 250 K.” It then asked, “What will the pressure become if the gas is heated to 350 K and allowed to expand into a volume of 500 mL?” Notice that you have no idea how many moles of gas are involved. This presents no difficulty as long as we assume that the number of moles of gas does not change.

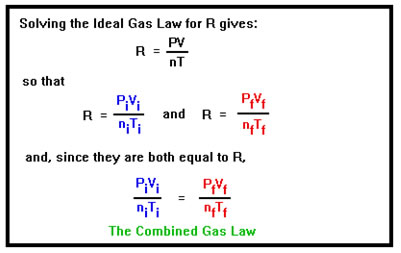

To solve this type of problem we take advantage of the fact that while P, V, n, and T can change, R does not: it’s a constant. Solving the ideal gas law for R give R= PV/nT, which must be true for both the initial and final conditions, so that the initial value of PV/nT must be equal to the final value of PV/nT since they are both equal to R. This is called the Combined Gas Law. This is nothing new. Mathematically, it is just another way of writing the Ideal Gas Law. We will see how it not only simplifies solving this type of problem, it also makes it easy to deal with the fact that we don’t always know all of the values for P, V, n, and T. |

|

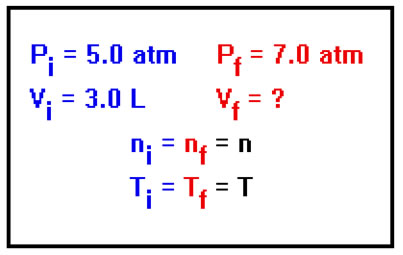

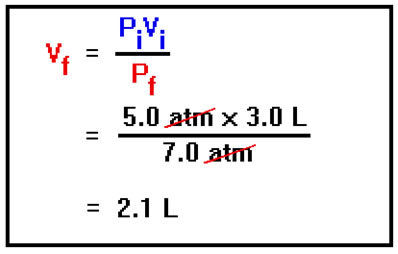

Here’s an example: Calculate the volume of a gas at P=7.0 atm if the gas occupies 3.0L at 5.0 atm, assuming n and T don’t change. In this problem we are not told either the number of moles of gas present or the temperature. The problem tells us to assume that neither n nor T change, but we would have to do so anyway even if it didn’t. We can’t solve the problem otherwise. |

|

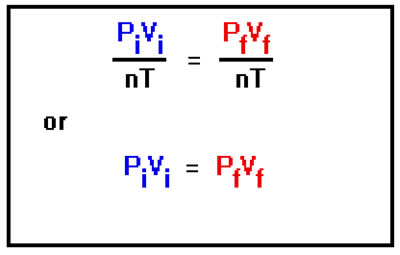

Since the initial and final values of the number of moles are the same, we’ll call them both n, and we’ll call both the initial and final values of temperature T, since T doesn’t change either. The result is that these variables cancel out, and disappear from the Combined Gas Law. In the future, you needn’t go through this procedure. In general, you can just leave out of the Combined Gas Law those variables whose values don’t change in the problem. Basically this amounts to extracting the various particular laws – Charles’ Law, Boyle’s Law, etc. – from the Ideal Gas Law. In this case, we have taken Boyle’s Law out of the Ideal Gas Law for this problem |

|

We now solve this simplified equation for the final value of the volume and substitute in the initial and final values of the pressure and the initial value of the volume. We simply divide both sides of the equation by Pf, then plug in the values for the initial and final pressure and the initial volume.

|

|

Notice that the final volume is just the initial volume multiplied by a “correction factor” – the ratio of the two pressures. Since the pressure has increased, the volume must decrease and this is reflected in the fact that the ratio of pressures is the smaller value divided by the larger.

In fact, you could have solved this problem using just that logic without having to go through solving the Combined Gas Law. To find the final value of any variable, simply multiply its initial value by one correction factor for each other variable that changes. In this case, since only the pressure changed, there was only one “correction factor.”

Example 32 in your workbook shows this problem and another sample problem. Make sure you understand how these two problems are solved before you move on.

If you like, try solving the second problem using both the Combined Gas Law and the correction factor approach. Make sure they give you the same answers. If you become good at using this latter method, it will save you considerable time. (Example 33 will walk you through some problems using the correction factor approach.)

Exercise 34 in your workbook gives two sample problems of this type for you to try. Be sure to try them on your own. You’ll find the answers below.

Answers to Exercise 34:

a. 1172 torr or 1.54 atm

b. 220 K or -53 oC

The next section of this lesson will discuss Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures (which you will need to understand in order to do the lab exercise for this lesson) and one final kind of problem: determining the molecular weight of an ideal gas.