Lesson 3: Homogeneous Mixtures

When dealing with solutions, we have to deal with both the condition of having different materials mixed so completely that they are homogeneous and the process by which they were mixed so thoroughly. In this section we will first deal with the generalities of mixing materials, then the more specific issues of mixing molecular materials and mixing ionic materials with water.

Mixing Materials | Mixing Molecular Materials | Mixing Ionic Materials with Water | Solubility Rules

Mixing Materials

What happens at the molecular level when materials mix together to form solutions? The ability of molecular materials to mix with one another depends, to a very great extent, on intermolecular bond types.

We will go into specifics soon, but first let's look at the basic idea of mixing as shown here. This "equation", if I can call it that, starts on the left with two materials, A and B, which have not yet been mixed. The right side of this "equation" shows the two materials after they have been mixed. What has happened to them in the process? The bonds holding the A's together were broken. The bonds holding the B's together were also broken. New bonds holding A and B together have been formed. |

|

In some ways this is like elements combining to form a compound, however it is not necessary for there to be a fixed ratio here. Also, we are not necessarily talking about covalent, ionic and metallic bonds, which we would be talking about if we were talking about making a new compound. In this case, there can be any number of A's mixed in with the B's. An example of this is shown in part B. The same thing is happening, it's just that the proportions are different. This process can be exothermic or endothermic depending on the strength of the bonds involved and whether more or less energy is released in making A-B bonds than is used in breaking A-A and B-B bonds.

In general, for mixing to occur, the bond strengths of A-A, B-B and A-B have to be comparable to one another. Otherwise, the materials will not mix very well. If, for example, the A-A bonds were much stronger than the B-B bonds, the A's would not separate from one another to let the B's in and no mixing would occur.

Next, we will apply these ideas first to the process of mixing molecular materials and then to mixing ionic materials with water.

Mixing Molecular Materials

Keep in mind that molecular materials come in two general categories: polar and nonpolar. Let's start this section by considering combinations of molecular materials that will give solutions.

There is an old rule of thumb, a generality, which goes like this: "Like dissolves like." A material which is made of polar molecules will dissolve in other materials which are made of polar molecules. Materials made of nonpolar molecules will dissolve in other things which are made of nonpolar molecules. "Like dissolves like."

Conversely, polar materials are generally insoluble in nonpolar materials and vice versa.

The reason for this is that all nonpolar molecular materials have van der Waals bonding, and thus all of the intermolecular bonding is of about the same strength. Polar molecular materials have stronger dipole-dipole bonds or hydrogen bonds. Different polar molecular materials will generally mix well with one another, but not with the nonpolar molecular materials. When you try to mix polar and nonpolar molecules together, they generally cluster together and stay bonded with their own type.

In this section we will first look at some examples and then consider the bond changes that take place when molecular materials dissolve in one another. (These examples are also set up for observation in the lab.)

Water and Carbon Tetrachloride

Water is a common example of a polar molecular material. Carbon tetrachloride is a common example of a nonpolar molecular material. If pictures of angular and tetrahedral molecules have not already sprung into your mind, perhaps I should refresh your memory. It might also be a good idea for you to stop and take a few minutes to draw the electron dot diagrams of these compounds and explain to yourself why they are such good examples of polar and nonpolar molecular materials. Ask for help if you need it. |

|

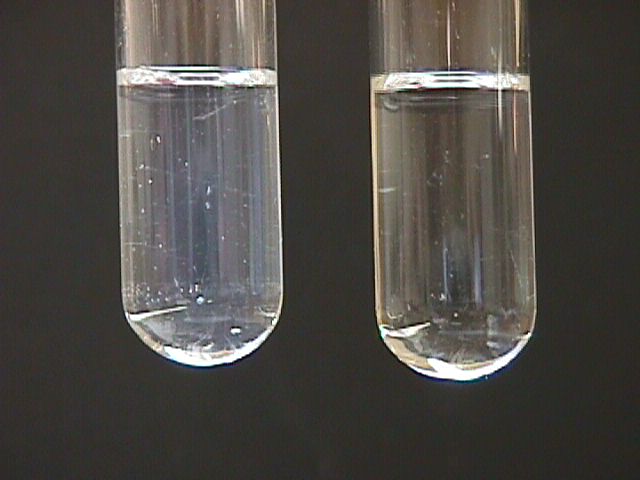

Let's test water and carbon tetrachloride to see if they are soluble or insoluble in one another. Write down your observations in exercise 4 in your workbook. I'll test them by putting about 1 mL of each into a test tube and then mixing them (left). If the two materials combine to form one homogeneous liquid, then they are soluble in one another. If they are insoluble in one another, then they will not combine to form one liquid, there will be two separate layers in the tube. As you can see, there are two layers (right). Polar water and nonpolar carbon tetrachloride are not soluble in one another. |

|

Next, let's test a few other things to see how soluble they are in water, and how soluble they are in carbon tetrachloride. Record your observations in exercise 5. You can base your observations on what you see here on the screen or by making your own observations in the lab when you are there.

IodineThe first test is to add a crystal of iodine (I2) to water (left) and to carbon tetrachloride (right). Both have had the same amount of time and stirring and you can see that the purple iodine crystal remains undissolved in the water but has dissolved in the carbon tetrachloride. As you record your observations note that iodine molecules are nonpolar. |

|

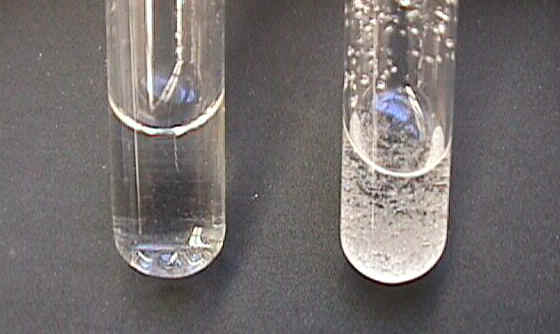

SugarHere [top] we have water (left tube) and carbon tetrachloride (right tube) with sugar. After [bottom] equal amounts of sugar have been added to both tubes and with the same amount of time and stirring, you can see that the sugar has dissolved in the water but has not dissolved in the carbon tetrachloride. As you record your observations, note that sugar molecules contain polar angular C-O-H groups. |

|

|

EthanolHere ethanol (ethyl alcohol) has been mixed with water (left tube) and with carbon tetrachloride (right tube). Note that ethanol mixes with both. Half of each ethanol molecule contains a polar C-O-H group and the other half contains essentially nonpolar C-H bonds. That gives ethanol molecules both polar and nonpolar characteristics. |

|

AcetoneAcetone is another molecular material with both polar and nonpolar characteristics. Here acetone has been added to water (left tube) and carbon tetrachloride (right tube). As you can see, it has mixed with both the polar water molecules and with the nonpolar carbontetrachloride molecules. |

|

More on IodineNext, let's extend our observations of iodine to include not only the solubility of iodine in water and carbon tetrachloride, but also in ethanol and acetone. From left to right the tubes contain water, ethanol, acetone and carbon tetrachloride. Approximately equal amounts of iodine were added to each tube and then stirred the same amount. You can see from the intensity of the colors that the amount of iodine that dissolves in each solvent varies. Nonpolar iodine is most soluble in nonpolar carbon tetrachloride and least soluble in polar water. |

|

|

The purpose of performing the tests above was to have you see that the "like dissolves like" rule of thumb is a crude approximation to things that actually happen. It is a valid rule, but not totally so. First of all, you cannot arbitrarily classify each and every material as being either nonpolar or polar. There are many degrees of polarity, all sorts of gradations in between the extremes of polar and nonpolar. You have seen that things such as ethanol and acetone are not only soluble in water, but also soluble in carbon tetrachloride. They are polar enough to dissolve in water, but not so polar that they won't dissolve in carbon tetrachloride. They are partly polar or slightly polar and they will dissolve in both.

When iodine was tested, you saw that it was very soluble in carbon tetrachloride and insoluble in water (very slighlty soluble if given a longer period of time). This is because iodine is nonpolar. You also saw that the iodine was less soluble in ethanol and acetone than it was in carbon tetrachloride. Ethanol and acetone are more polar than carbon tetrachloride. Iodine was more soluble in them than it was in water because they are less polar than water. In summary, the solubility of iodine decreased as the polarity of the solvent increased.

You should remember the phrase, "Like dissolves like," but also remember that it is an over-simplification of the way that chemicals actually interact with one another.

Before we go on to the next topic, let's go over the bond changes that took place in exercise 4 and 5.

First, in exercise 4 no bond changes occurred, because no mixing took place. Water molecules have hydrogen bonding between the molecules and carbon tetrachloride has van der Waals bonding between the molecules. The bonding between water molecules and carbon tetrachloride molecules would have to be van der Waals because that is all that carbon tetrachloride can do. If any mixing had happened, it would involve breaking van der Waals bonds in the carbon tetrachloride, breaking hydrogen bonds in the water, and forming van der Waals bonds in the mixture. Because that would involve breaking strong bonds to form weak ones, mixing does not happen.

When ethanol dissolves in water, things are a little different. In this case both ethanol and water have hydrogen bonding between molecules. Ethanol and water molecules can hydrogen bond to one another. Mixing, in this case, involves breaking hydrogen bonds between water molecules, breaking hydrogen bonds between ethanol molecules, and making hydrogen bonds between water and ethanol molecules. Since the bonds formed are about the same as the bonds broken, mixing does occur.

I would like you to go through the rest of those chemicals, those combinations you just worked with, and decide, in each case, what kinds of bonds would be broken and what kinds of bonds would be formed. Once you have done that, check you answers below to make sure that you are properly identifying the bond types that are involved in the mixing or non-mixing as it occurred in each sample.

Answers

Note that in the following answers, the answers in quotes are the bonds that would have formed if mixing had occurred. It would also be correct to say that bonds were neither broken nor formed because no mixing occurred.

- Iodine in water: Break van der Waals and hydrogen, "form van der Waals."

- Iodine in ethanol: Break van der Waals and hydrogen, "form van der Waals."

- Iodine in acetone: Break van der Waals and dipole-dipole, "form van der Waals."

- Iodine in carbon tetrachloride: Break van der Waals, form van der Waals.

- Sugar in water: Break hydrogen, form hydrogen.

- Sugar in carbon tetrachloride: Break hydrogen and van der Waals, "form van der Waals."

- Ethanol in carbon tetrachloride: Break hydrogen and van der Waals, "form van der Waals."

- Acetone in water: Break dipole-dipole and hydrogen, form dipole-dipole.

- Acetone in carbon tetrachloride: Break dipole-dipole and van der Waals, form van der Waals.

Mixing Ionic Materials with Water

Solubility of Ionic Compounds in Water

Next, let's test the solubility of three calcium compounds in water by mixing a small amount of each with about 1 ml of water. Record the results of the solubility tests shown below (or you can test them yourself in the lab) in exercise 6 in your workbook.

|

|

|

|

|

The purpose of doing this particular experiment is to give you some firsthand experience in realizing that some ionic compounds are soluble in water and some are not.

Mixing Ionic Materials with Water

As you know, table salt (as well as calcium nitrate and calcium chloride) will dissolve in water. Since salt is not a polar molecular material, there must be more to solubility and mixing than matching intermolecular bonds.

This should help you to picture what happens to salt as it dissolves in water. Salt is made up of sodium and chloride ions held together by ionic bonds. |

|

When sodium chloride breaks up, ionic bonds are broken. As the sodium and chloride ions move between the water molecules, the hydrogen bonds holding the water molecules together must also be broken. Because water molecules are polar, they have a positive end (H) and a negative end (O). |

|

The positive ends of the water molecules are attracted to the negative chloride ions and the negative ends of the water molecules are attracted to the positive sodium ions. These attractions between ions and polar molecules are called ion-dipole bonds. They are comparable in strength to hydrogen bonds or maybe even a bit stronger. When an ionic material, like salt, dissolves in water, both ionic bonds and hydrogen bonds are broken and ion-dipole bonds are formed. |

|

"Table salt" (sodium chloride) is soluble in water. However, not all ionic compounds are soluble in water. Many are, many are not. How soluble an ionic compound is in water depends on the strength of the ionic bonds that have to be broken and on the number and strength of the ion-dipole bonds that are formed. Later we will deal with some of the consequences of these bond changes.

How to Determine Solubility

How can you tell whether or not an ionic material is going to be soluble in water? With ionic compounds, the most direct way to tell whether or not the material is soluble is to try it. We don't have a single rule such as "like dissolves like" for ionic compounds. If you want to find out if calcium nitrate is soluble in water, you get some calcium nitrate and put it in water and you see if it dissolves.

Another way is to realize that someone else has probably already tested that compound and written down the results in the "Handbook of Chemistry and Physics" or some other books. So you can look up that particular compound to see whether it is soluble in water.

A third way, one that you need to become familiar with, involves the use of solubility rules, which are presented on the next part of this section.

Solubility Rules

Solubility Rules for Ionic Compounds

You will be responsible for being able to use the solubility rules, but you will not be responsible for memorizing the solubility rules. A table of solubility rules is in your workbook as example 7. If you would like a brief explanation of what is contained in the table, read on. If the table is self-explanatory to you try your hand at exercise 8 in your workbook (also shown below) and then check your answers at the bottom of this page.

Explanation of the Solubility Rules Table

The first column lists the "type of compound" and the next two columns list which of those substances are soluble and which are insoluble or slightly soluble.

Nitrates (i.e. ionic compounds containing nitrate ions), it says, are all soluble. Chlorides, it says, are all soluble except for some that are listed as copper(I), lead(II), mercury(I) and silver.

All sulfates are soluble except those listed under the insoluble category.

With hydroxides the pattern turns around. The previous pattern was that most compounds were soluble with some exceptions. With hydroxides it is the other way around. There is a short list of those that are soluble: NaOH, KOH, NH4OH, Ca(OH)2, Sr(OH)2, Ba(OH)2. The rest of them are insoluble.

For sulfides, again there is a short list of soluble ones while the rest are insoluble. Again with carbonates and phosphates we have a short list of soluble ions with these polyatomic ions and all the rest are insoluble. Perhaps you noticed that the group 1-A metals (Na+ and K+) and ammonium ion were always listed as being soluble. So that can be another rule, and it is shown on the last line. |

SolubilityRules for Ionic Compounds: (Also shown in example 7 in your workbook.)

|

Practice Using the Solubility Rules

Now you should use these solubility rules to decide whether or not some compounds are soluble. So take some time now to determine whether the following compounds are soluble or insoluble. (These are also listed in exercise 8 in your workbook.) After you have done that, check your answers below.

| NaOH | Fe2S3 | MgSO4 | PbCl2 | Ba(NO3)2 | MgCO3 |

Answers

| NaOH | Fe2S3 | MgSO4 | PbCl2 | Ba(NO3)2 | MgCO3 |

| soluble | insoluble | soluble | insoluble | soluble | insoluble |

Note that Fe2S3 is a sulfide rather than a sulfate.