Lesson 3: Solubility Limits

So far in this lesson we have described materials as being soluble, slightly soluble, or insoluble in water. Let's get into more precision by considering the degree of solubility in both specific (quantitative) and relative terms (saturation). Then we'll consider ways in which those limits can be exceeded and the concept of dynamic equilibrium.

Degree of Solubility | Saturation | Exceeding the Limits | Dynamic Equilibrium

Degree of Solubility

Degree of Solubility

If you were to look up a chemical in the "Handbook of Chemistry and Physics" to find out whether it was soluble or not, you might find that it says that the material is soluble, or that it's insoluble, or that it's slightly soluble; or you might find a number. |

|

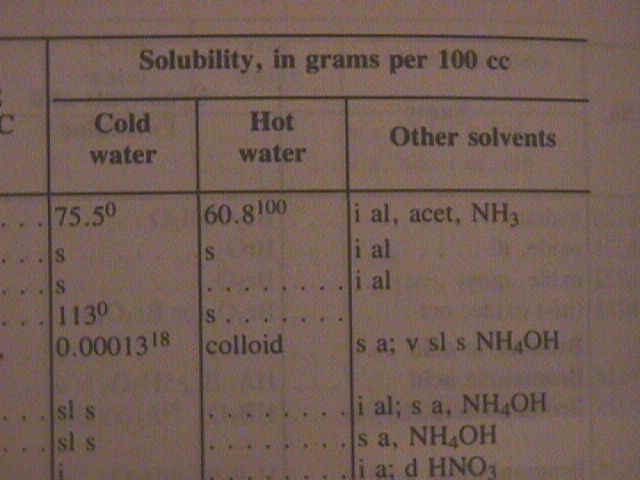

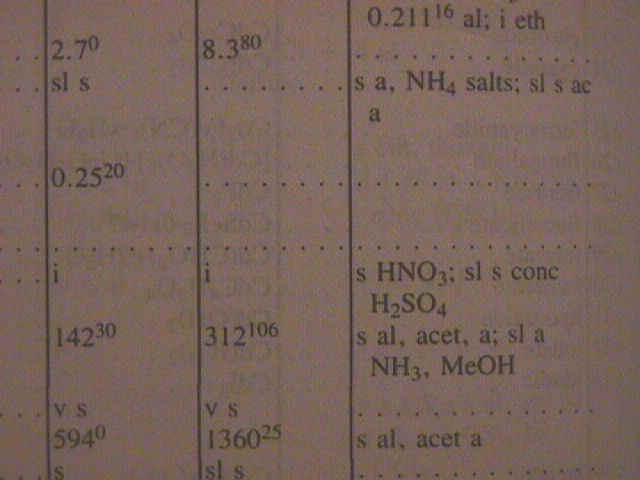

In those cases where a number is given, it is the number of grams of the material that will dissolve in 100 cubic centimeters of water. The degree of solubility of a chemical is often expressed in grams per 100 cc, that is, grams of the material that will dissolve in 100 cc (or ml) of water. |

|

The temperature does influence the degree of solubility. You can see that values are given for solubility in both cold water and hot water. Sometimes the actual temperature at which the measurement was made is given as a superscript. Notice that for the first compound the solubility decreases when the temperature goes up. More often the solubility will increase when the temperature goes up. |

|

Saturation

These values for degree of solubility (usually just referred to as solubility) refer to the limit of how much solute will dissolve in a certain amount of water at a certain temperature.

A solution which is below that limit is called an unsaturated solution. Most of the solutions that we deal with are unsaturated solutions.

When a solution is at its limit, we call the solution saturated. Any more solute put into the water will not dissolve.

There are ways of exceeding the solubility, but that won't happen just by adding more solute. A solution which has exceeded its solubility limit is called a supersaturated solution. We will look at that phenomenon in the next section, Exceeding the Limits.

Exceeding the Limits

The limits of solubility can be exceeded in two ways that we will explore in this lesson. The first is to adjust the temperature of the solution while it is being prepared to achieve supersaturation. The second is to mix separate solutions together to achieve precipitation. Eventually, both of these methods result in the formation of a solid that crystallizes from the solution. When and how that happens is different for each, but why it happens is the same. In each case the concentration of the ions in the solution have been temporarily pushed past what the solution can hold.

Supersaturated Solutions

Supersaturated solutions are, to me, absolutely fascinating. They are fascinating because they exceed the solubility limit. In a sense they violate the definition of a saturated solution. When people talk about saturated solutions, there is always a temptation to say - "there is an absolute limit as to how much solute will go into the solution and you can't put any more than that in" - but you can, if you do it right.

When you have a solution at its limit of solublity and you add more solute, it doesn't dissolve. That is true. But you can make it dissolve by changing the conditions. Quite often, if you heat up the solution, the solubility of the solute will increase. By heating up the solution more solute can dissolve.

Once you get the "extra" solute into solution then you can cool the solution back down and sometimes keep that extra amount of solute in solution. When that does happen, you have a very unstable situation. The extra solute, the solute that "should not" have dissolved, can crystallize out of solution quite easily. If you add just a little bit of crystal, then the excess solute will crystallize out of the solution. Sometimes, all you have to do is scratch the inside of the test tube or the container that the solution is in, and it will crystalize on the scratch. I'd like to have you become familiar with this unusual kind of solution by doing the experiment with a supersaturated solution that is described in exercise 10 in your workbook when you come to the lab.

Precipitation

Living in the Northwest, we have lots of experience with "precipitation," mostly as rain, sometimes as hail or snow. But to a chemist, "precipitation" means something quite different. Just as you had to start thinking about the word "significant" a bit differently (when you learned about significant digits in CH 104), you will have to get used to thinking about the term "precipitation" differently.

As you have seen earlier in this lesson, solubility rules can be used to figure out whether a certain combination of ions will come apart and dissolve in water. Some will and some won't.

Solubility rules can also be used to figure out whether ions that are already in solution will remain apart or come together.

For example, the rule for hydroxide says that sodium hydroxide is soluble. That means that if you start with solid sodium hydroxide, sodium ions and hydroxide ions will separate and go into solution. It also means that if you start with dissolved sodium chloride, the ions will not come together out of solution to form a solid material. As another example, the rule for chlorides says that lead(II) chloride is insoluble. That means that if you start with solid lead(II) chloride, the ions will not separate and go into solution. That also means that if you start with lead(II) ions and chloride ions already in solution, they will come together to form a solid material that we say precipitates out of solution.

Predicting Precipitates

In exercise 9 you will use the solubility rules to figure out whether certain combinations of ions will remain in solution when they are mixed or come together and form insoluble precipitates.

A complicating factor in figuring this out is that each ionic solution contains both positive ions and negative ions. Consequently, there are two combinations that must be considered. For example, when barium nitrate is mixed with copper(II) sulfate, one possible combination is copper(II) nitrate and the other is barium sulfate. According to the nitrate rule, all nitrates, including copper(II) nitrate, are soluble. According to the sulfate rule, barium sulfate is insoluble. Therefore this combination of ions will form a precipitate and that precipitate will be barium sulfate. We can test that prediction by mixing the solutions and seeing what happens.

We will discuss predicting precipitates in more depth in a later section in this lesson.

Dynamic Equilibrium

The previous sections on this page have provided you with a lot of information about solutions, but only a little about the process by which they are made.

You've seen that if you take something like salt, and put it into water, the solid material breaks down, disappears and goes into solution. We call that process "solution," "dissolution," or "dissolving."

You have also seen, in the supersaturation demonstration, how material can crystallize, that is, come out of solution and form crystals.

Because you've seen ionic materials dissolve and you've also seen ionic materials crystallize, you know that the process is not a one-way process. It can go in either direction.

Let's go over the process step by step.

- When you put an ionic material into water and watch it dissolve, you can see that the solid is getting smaller. You know that the ionic material is breaking up and going into solution.

- You also know that you can add so much of that solid that it will not all dissolve. That is, you can have a saturated solution.

- When you have reached the saturation point, the dissolving process does not really stop. But what happens is that the crystallization process is occurring at the same rate that the dissolution process is occurring.

- At the saturation point, there is a balance between the amount of material that is dissolving, and the amount of material that is crystallizing at the same time.

The amount of material in each condition (or state) remains the same but the process of change from one state to the other continues. Solid material continues to dissolve, and material that is in solution continues to crystallize. Dissolution and crystallization are occurring at the same rate. There is a balance between those two opposite reactions, and we call that kind of balance a dynamic equilibrium -- "equilibrium" because there is a balance, "dynamic" because there are changes taking place.

A saturated solution is considered to be in dynamic equilibrium because there is molecular change that is occurring in opposite directions at the same rate, such that there is no net observable change. All you can see is that there is a certain amount of solid and a certain amount of solution, you cannot see that one is changing into the other. Thus, a saturated solution in contact with undissolved solute is an example of a dynamic equilibrium.

Shifting Equilibrium

We can alter this situation in a number of ways and doing so will cause a shift in the equilibrium balance.

Let's look first at what would happen if we added more water or solvent. The concentration of the solute would be less than it was and it would no longer be saturated. More of the solute would be able to dissolve.

On the other hand, if we evaporated away some of the water or solvent, the solute would become more concentrated and if it was already saturated, some of the solute would have to crystallize out of the solution. Or perhaps it would become a supersaturated solution.