Lesson 8: Collision Theory

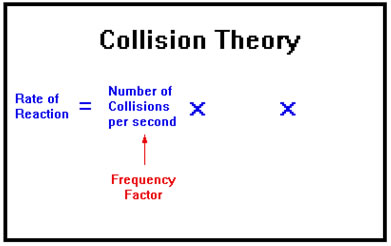

The collision theory of reaction rates identifies three factors that determine the rate at which a given chemical reaction will take place. It is based on the simple idea that reactions occur as a result of collisions between atoms and molecules.

This theory is based on simple physics. Its predictions, on the whole, have been remarkably accurate and today it is the generally accepted explanation for the variations we see in reaction rates.

Frequency Factor | Energy Factor | Probability Factor | Surface Area | Activation Energy | Catalysts

Frequency Factor

Since, in order to react, molecules must collide, the first factor that determines reaction rate is the number of collisions that occur per second. This is called the frequency factor. It is determined by how many molecules there are per unit volume – that is, their concentration – and the speed with which they are moving.

As the number of particles in a given volume increases, the number of times they bump into each other each second also increases. The speed of the particles also influences collision rate. The faster the particles are moving, the more often they collide. This corresponds with our common sense – when you drive, you’re more likely to collide with another car on a crowded street moving at high speed than you are in a nearly deserted parking lot traveling only a few miles per hour.

The frequency factor depends mostly on how many molecules are present in a given volume – their concentration. To a lesser extent it is influenced by the temperature, since the higher the temperature the faster the molecules move and the more frequently they collide.

|

A ten degree rise in temperature (from, say 20 to 30 oC) represents only about a 3.8% increase in kinetic energy and only about a 1.8% increase in the velocity of the particles. A modest increase in concentration, however, say from 0.1 molar to 0.2 molar of a single reactant, results in a 100% increase in the number of collisions per second and a doubling of the rate of reaction. |

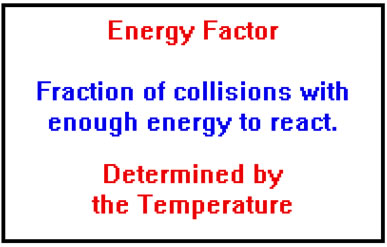

Energy Factor

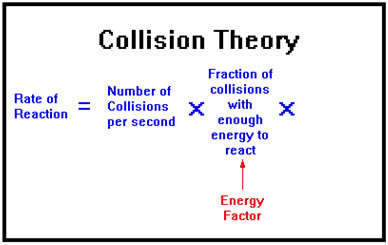

A second factor is based on the idea that in order for a reaction to take place, the collision must occur with sufficient force. Thus the second factor is the fraction of the collisions that have sufficient energy to cause a reaction.

This factor exists because in most reactions, before new bonds can form, old bonds must be at least partially broken. Breaking bonds requires energy, and one way to inject sufficient energy into a molecule to break a bond is to collide it with another molecule at high enough speed. The minimum speed required depends on the strength of the bond.

This factor, called the energy factor, changes with the temperature: higher temperature results in faster motion and, on the average, more violent collisions, so the fraction of collisions with the minimum energy needed to react also increases.

|

This factor is quite sensitive to temperature. For a reaction in which the minimum energy needed to cause a reaction is 12 kcal/mol, increasing the temperature from 20 to 30oC results in a 97% increase in the fraction of collisions with sufficient energy to react. In fact, a very rough general rule of thumb is that reaction rates double for every 10o rise in temperature. |

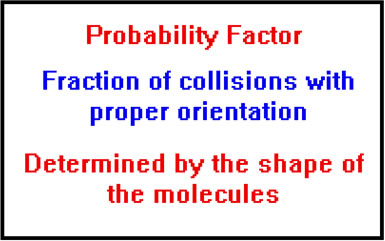

Probability Factor

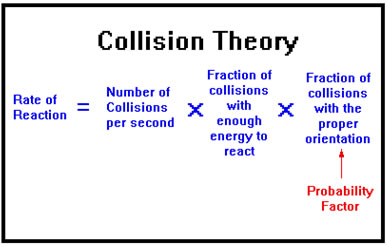

Often a reaction cannot take place unless the colliding molecules have the correct orientation, that is, they are turned in the right direction as they collide. The fraction of collisions that have the proper orientation is called the probability factor.

Suppose, for example, that the molecules in one liter are colliding 10,000,000 times per second, if half those collisions have sufficient energy have the proper orientation, then the number of reactions that occur per second will be 10,000,000 x ½ x ½ = 2,500,000 reactions per liter per second.

This factor is determined by the nature of the reaction and the shapes of the molecules involved. It does not change when external conditions such as concentration and temperature change. For this reason we will be less interested in the probability factor than in the frequency and energy factors.

|

In very simple terms, bonds break when they are set to vibrating too violently. To cause bonds to vibrate, collisions must be “head on.” A sidelong collision will cause a molecule to rotate, but not to vibrate. |

We have seen how increasing the concentration increases the rate of a reaction by increasing the number of collisions per second, and how increasing the temperature increases the rate of a reaction mostly by increasing the fraction of collisions that have sufficient energy to react.

We’ll now use the collision theory to explain the effects of several other factors on the rates of reaction, namely the available surface area of a solid reactant, the activation energy, and the presence of a catalyst.

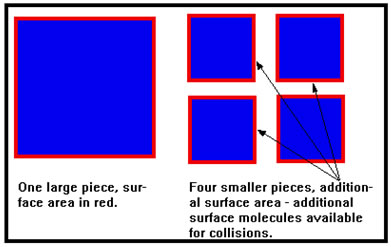

Surface Area

When a solid reactant is broken into smaller and smaller pieces, the rate at which it reacts increases. Since only the molecules on the surface of the solid can collide with other molecules, the greater the surface area, the more collisions can take place per second, and the faster the reaction.

|

Occasionally this is dramatically (and tragically) illustrated in grain elevators, where very small particles of grain dust or flour offer such a large surface area that combustion, if allowed to occur, can do so at an explosive rate. Grain elevator explosions were unfortunately common before strict safety regulations were imposed. |

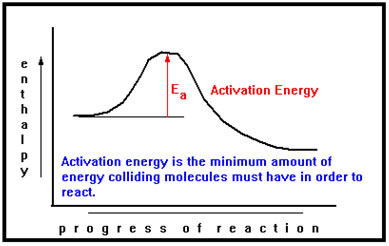

Activation Energy

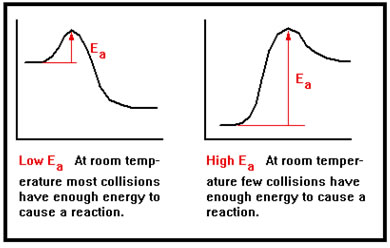

Activation energy, which you should recall from the reaction diagrams we did in the previous section, measures the minimum energy needed for a reaction to occur.

|

This minimum energy is determined by the strength of the bonds that must be broken, by the strength of any bonds formed at the same time, and by the relative timing of the two events. It is rare that one bond must be completely broken before a new bond can start to form. The energy released as the new bond forms provides some of the energy needed to break the old bond, lowering the amount of energy that the collision needs to provide, and thus the activation energy. |

If the activation energy is low, a larger fraction of collisions will have sufficient energy to react than if the needed activation energy is high. Thus, higher activation energies are associated with slower reactions and lower activation energies with faster reactions. |

|

While, in general, exothermic reactions tend to have low activation energies and endothermic reactions high ones, this is, fortunately, not always the case. If it were, gasoline, for example, would spontaneously burst into flame on contact with the air. Instead, a significant amount of activation energy is required (and supplied at precisely the right moment by a spark plug to make the internal combustion engine work properly). Once the activation energy is supplied, however, the energy released by the reaction of one molecule can supply the activation energy required for additional molecules to react, and the reaction continues without further input of energy from the outside.

Catalysts

A catalyst is a substance that increases the rate of a reaction without itself being consumed in the process.

Catalysts are used extensively in chemical manufacturing but are little known outside the industry. One exception is the catalytic converter used in automobile exhaust systems. Normally exhaust gases break down very slowly, but when they come in contact with the catalyst in the converter, they react very rapidly to form much less toxic and harmful gases that do less damage to the environment. The demise of lead in gasoline was due in large part to the fact that it reacted with the catalysts in the catalytic converters and dramatically reduced their ability to function.

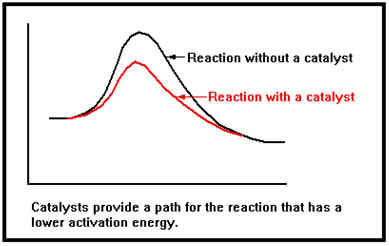

Catalysts work by providing an alternate mechanism, or path, for the reaction that has a lower activation energy than the original path. In a sense, catalysts provide an easier way to get from reactants to products and the lower activation energy results in a faster reaction. |

|

As catalysts are not used up in the reaction, a relatively small amount of catalyst can be quite effective in increasing the overall rate of a reaction because they can be used over and over again by subsequent reactant molecules. Thus they are not only an effective way of speeding up reactions, they are a cost-effective way as well.

Experiment 7 in your workbook illustrates the effects of these various factors on the rate of the reaction between magnesium metal and hydrochloric acid. This is the first part of a two-part lab for this lesson.

Since there is no known catalyst for this reaction, we can’t illustrate the effect of catalysts. However, we do explore the effects of concentration, temperature, and the surface area of the solid on the rate of the reaction.