Lesson 8: Equilibrium Constants

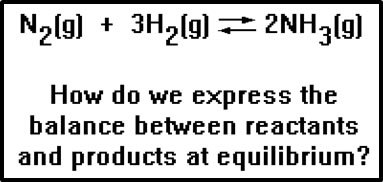

As its name suggests, “equilibrium” is a balance – a balance between the forward and reverse rates of a chemical reaction. But the balance exists also between the concentrations of the reactants and products.

We expect that for any given reaction, the concentrations of the reactants and the products at equilibrium will be related to one another, and that relationship will be determined by the intrinsic rates of the forward and reverse reactions. For a reaction with a fast forward rate and a slow reverse rate, for example, we expect that at equilibrium, the concentrations of the products will be high and that of the reactants will be low.

It’s much easier to measure concentrations than rates, and, as it turns out, it’s much easier to characterize the situation at equilibrium using concentrations. In fact, all you need is a balanced equation and measured values for the concentrations of reactants and products at equilibrium.

Given the balanced equation, all you need to know to determine the concentrations of the reactants and products at equilibrium is:

- How much of each reactant and product you started with; and

- The concentration of just one of the reactants or products at equilibrium.

Although that calculation is not difficult, we will always give all of the equilibrium concentrations.

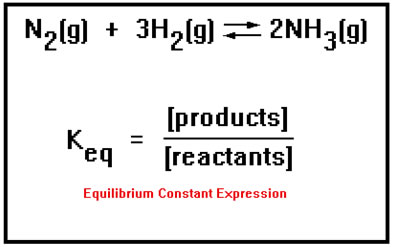

The position of equilibrium is described by a constant, Keq, called the equilibrium constant. It is equal to the ratio of product over reactant concentrations. The equation is called the equilibrium constant expression. The ratio is constructed in this way (products divided by reactants) so that the constant will be a large number if the concentrations of products are large (that is, the equilibrium favors the formation of products) and the constant will be small if the concentrations of products are small. In a sense, the equilibrium constant is a measure of the extent to which the reaction goes to completion. |

|

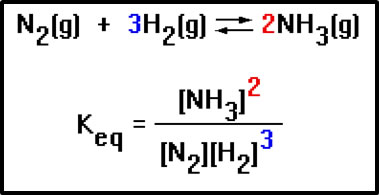

The exact expression is constructed by taking the concentration of each product and reactant, raising it to a power equal to its coefficient in the balanced equation, then placing the product concentrations on the top of the ratio and the reactant concentration on the bottom of the ratio. The brackets mean “concentration of,” so the notation [N2] means “concentration of N2” – usually given in moles per liter (molarity).

|

|

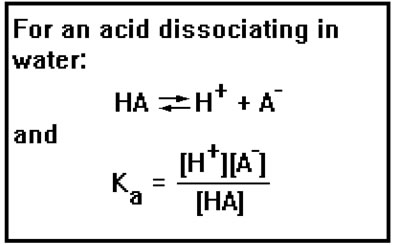

You may recall seeing an equation similar to this one in the last lesson where we discussed buffer solutions. That equation was just the equilibrium constant expression for the dissociation of an acid in water:

HAH+ + A-

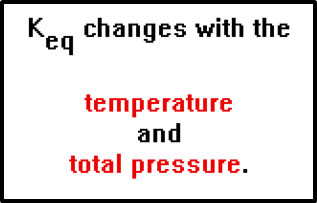

The equilibrium constant, Keq, has a value that is influenced by the temperature and by the total pressure. In this lesson, we will ignore the variation of Keq with T and P and assume in the calculations and problems that we do that these variables don’t change.

|

You already know that changing the temperature can shift the position of equilibrium and that raising or lowering the total pressure by decreasing or increasing the volume of the container can also shift the position of equilibrium, so it shouldn’t surprise you that Keq changes when these two parameters change. |

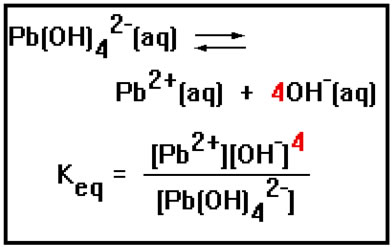

Here’s another example of an equilibrium constant expression. Notice again that the exponents in the expression are just the coefficients in the balanced equation.

|

Because x1 = x, when the exponent is 1, we don’t write it, just as we don’t write the 1 when it is the coefficient in the balanced equation. |

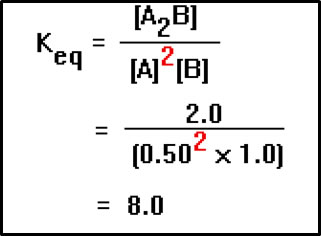

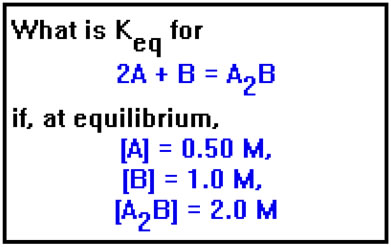

If we know the values of the concentrations at equilibrium, it’s easy to calculate the value of Keq. Suppose, for example, that for the hypothetical reaction shown, we measure the equilibrium concentrations of A, B, and A2B and find them to be 0.50 M, 1.0 M, and 2.0 M, respectively.

Try doing this problem on paper before you go on.

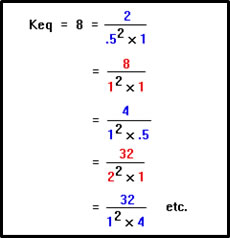

The equilibrium constant expression is [A2B] divided by the product of [A]2 times [B]. Substituting the values for the concentrations into this expression, we find that the value of Keq is 8.0. In most equilibrium constant calculations we ignore the units. In this example, units of Keq would be mol-2L2. But the units of Keq vary, depending on the relative numbers of moles of reactants and products in the balanced equation. Since there is no single, universally applicable set of units for the equilibrium constant, we normally do not include them at all. |

|

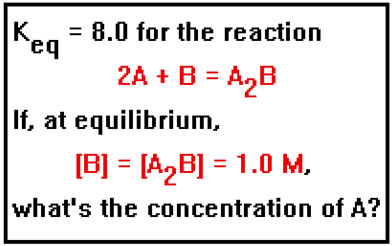

Here is a slightly different kind of problem. Suppose that we know the concentrations of all of the reactants and products at equilibrium but one, and we also know the value of the equilibrium constant. We can use the equilibrium constant expression to calculate the concentration of the unknown reactant or product.

|

Again, we will ignore the units of the equilibrium constant and assume them to be appropriate to the values of the concentrations expressed in moles per liter. |

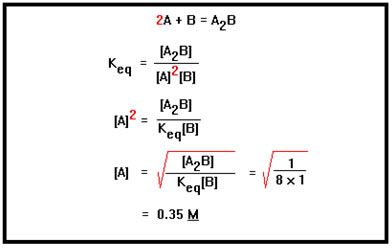

Again, we start with the equilibrium constant expression. We then solve it for the variable whose value we want: in this case, the concentration of A.

|

One way to check our calculations is to substitute the values of the concentrations back into the equilibrium constant expression to see if they give us the correct value for Keq: 1/(0.352 x 1) = 8.2. Pretty close. The discrepancy is due to our having rounded the answer to 2 digits – had we rounded [A] to three digits, we would have gotten 8.0. |

Notice that there are many, in fact an infinite number, of combinations of concentrations that satisfy the equilibrium constant expression. The expression for a given reaction tells us at equilibrium not what the concentrations are, but what the relationship between them must be. That relationship is determined by the relative rates of the forward and reverse reaction. In fact, it is equal to their ratio. |

|

Exercises 11 through 14 in your workbook provide you with some practice problems of these two types to try. If you can, stop now and work through these exercises before you continue. You’ll find the answers below.

Answers to Exercises 11-14:

11. Equilibrium Constant Expressions

a. Equilibrium constant expression for the reaction

N2(g) + 3 H2(g)![]() 2 NH3(g).

2 NH3(g).

Keq = |

Where [ ] represents equilibrium concentrations. Notice that substances on right of equation go on top of the expression and coefficients in equations become exponents. Concentrations are multiplied together.

b. Write the equilibrium constant expression for:

2 A + B2![]() A2B + B

A2B + B

Keq = |

|

12. Calculating Equilibrium Constant Values

a. Calculation of Keq for reaction 2 A + B

A2B if at equilibrium:

[A] = 0.50 M [B] = 1.0 M [A2B] = 2.0 M

| Keq = |

|

= |

|

= 8.0 |

b. Calculate the numerical value of Keq for the reaction

X + 3 Y ![]() XY3

XY3

if at equilibrium [X]=0.1 M, [Y]=2.0 M, and [XY3]=0.4 M.

| Keq = |

|

= |

|

= 0.5 |

14. Practice with equilibrium constants:

a. Write the equilibrium constant equation and calculate the value of the equilibrium constant for this reaction:

Ag+ + 2 NH3 ![]() Ag(NH3)2+

Ag(NH3)2+

[Ag+] = 3.0 x 10-11 M

[NH3] = 1.0 M

[Ag(NH3)2+] = 5.0 x 10-4 M

| Keq = |

|

= |

|

= 1.7x107 |

b. For the reaction A + B

C, which of the following cases is not at equilibrium (given that only one is not)?

Case I: [A] = 5 [B] = 2 [C] = 1

Case II: [A] = 2 [B] = 5 [C] = 1

Case III: [A] = 4 [B] = 5 [C] = 2

*Case IV: [A] = 1 [B] = 5 [C] = 2

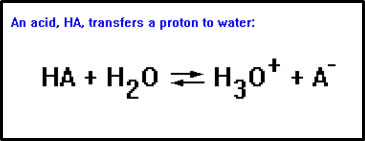

Equilibrium constants are often given special subscripts and names to indicate the type of reaction they are associated with. You might remember that in the last lesson we used an equilibrium constant expression for the dissociation of an acid. In that expression, we gave the equilibrium constant the symbol Ka and called it the acid dissociation constant.

|

We used Ka in our discussion of buffer solutions. In fact, we used it to compute the [H+] from the concentrations of acid, HA, and conjugate base A- in the buffer, a problem similar to the one we just solved – we computed the concentration of one reactant from the concentrations of the others and the value of the equilibrium constant. |

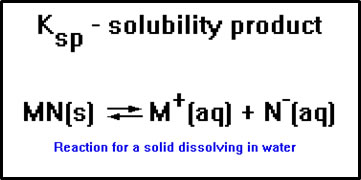

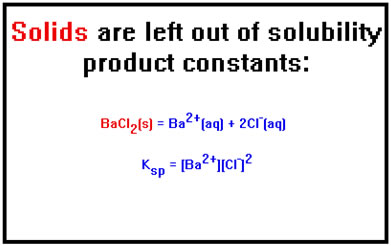

Another is Ksp, where the “sp” stands for solubility product. This equilibrium constant is associated with reactions in which a solid dissolves in water.

|

In this equation, M+ represents a metal ion and N- a nonmetal ion. Some specific examples of this type of reaction are: |

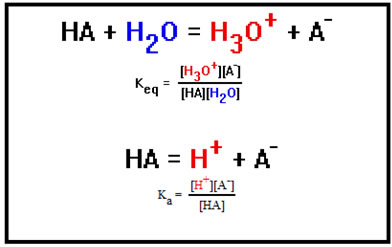

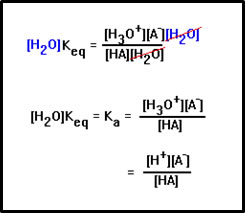

When we discussed acids, we said that what actually happens when an acid dissociates is that it transfers an H+ ion to a water molecule according to the reaction shown.

The H3O+ ion, you’ll recall, is called the hydronium ion. When we talk about the H+(aq) ion, we are actually talking about the hydronium ion. It’s just easier to write it as H+ than H3O+.

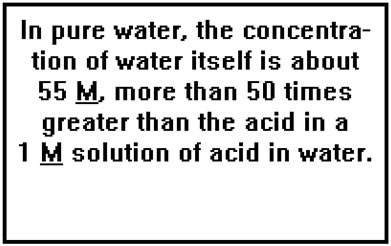

The equilibrium constant expression for this reaction includes the concentration of water. Comparing this to the acid dissociation constant expression we wrote before, you can see that [H+] is just another way of writing [H3O+], but that the concentration of water is missing from the earlier expression.

As you will see, both expressions are correct, although the top one is just slightly more accurate.

In an aqueous solution of acid, unless the concentration of acid is very high, the amount of water present is much, much greater than the amounts of the other reactants and products. In the course of the reaction, its concentration changes very little. One liter of water, 1,000 milliliters, weighs 1,000 grams. In 1,000 grams of water there are (1,000 g)/(18 g/mol)= 55.5 moles. Thus the concentration of water in pure water is about 55.5 mol/L. |

|

If we assume that the concentration of water is essentially constant, we can multiply both sides of the equilibrium constant expression by this concentration and Keq[H2O] will still be a constant, which we call Ka, the acid dissociation constant.

|

|

This, of course, introduces a slight error into our calculations, and the size of the error increases as the concentration of acid increases. In general, the error is less than 1% as long as the concentration of the acid stays below about 0.5 M. |

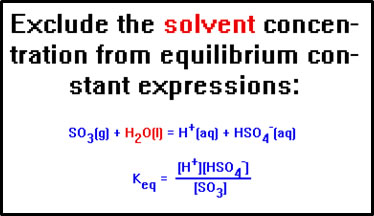

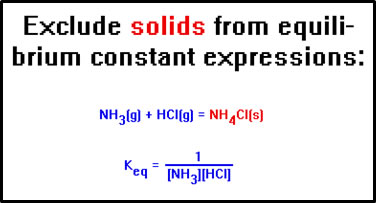

Since it is true, in general, that in solutions the concentration of the solvent is very large compared to the concentrations of the other species in solution, the concentration of the solvent is never included in the equilibrium constant expression.

How do we know that water is the solvent in this equation? The ions carry the notation (aq), aqueous, which means “dissolved in water.”

And this is done not just for aqueous solutions, but for any solution, no matter what the solvent.

For a slightly different reason, the same rule applies to solids. Since the solid phase is not dispersed throughout the volume of the solution, its concentration does not change as it dissolves. Therefore, in writing solubility products for a solid dissolving, the concentration of the solid is also left out of the expression.

|

Consider, for example, a hypothetical solid, one mole of which occupies a cube whose total volume is one liter. Its concentration is therefore 1 mol/1L, or 1M. If we now dissolve half the solid, what remains is 0.5 mol and half the cube, whose size has therefore shrunk to 0.5 L. The concentration of the solid is 0.5 mol/0.5 L, still 1 M. |

This, also, is more generally applicable. In any reaction, the concentrations of any solids involved are omitted from the equilibrium constant expression.

|

This also introduces a small error into the calculation. The rate of the reaction is influenced not so much by the concentration of the solid, but by its available surface area, and this does change slightly as the reaction proceeds. In general, however, the error is small and we can ignore it. |

Exercise 15 in your workbook provides some additional practice with equilibrium constant problems. Be sure to try these problems on your own and then check your answers below.

Answers to Exercise 15:

15. Practice problems: Equilibrium concentrations

a. For the reaction A(g) + B(g)

AB(g), Keq = 3.5.

If at equilibrium [A] = .1 M and [B] = 2 M, calculate [AB].

[AB] = 0.7 M

b. The Ksp for AgCl is 1.6 x 10-10. If Ag+ and Cl- are both in solution and in equilibrium with AgCl. What is [Ag+] if [Cl-] = 0.0050 M?

[Ag+] = 3.2x10-8 M

c. For the reaction PCl5

Cl2 + PCl3, the equilibrium constant value at a particular temperature is 9.0 x 10-2. What is the concentration of PCl5 if [Cl2]=0.020 M and [PCl3]=0.30 M?

[PCl5] = 0.067 M

d. In the same reaction, and at the same temperature, calculate what concentration PCl5 would have to be if the concentrations of both Cl2 and PCl3 were doubled.

[PCl5] = 0.27 M