Lesson 8: Chemical Reactions at Equilibrium and LeChatelier's Principle

Reactions at Equilibrium | Le Chatelier's Principle

Reactions at Equilibrium

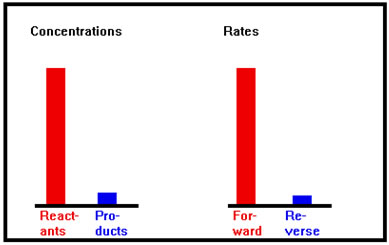

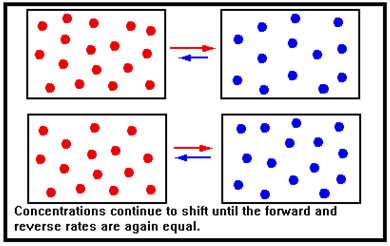

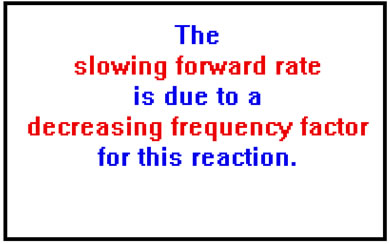

As a reversible reaction proceeds, the forward rate slows down while the rate of the reverse reaction speeds up. Let’s examine why this is so.

Initially, concentration of reactants is high and concentration of products is low; forward rate is much faster than reverse rate. |

|

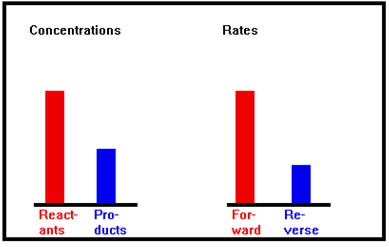

More product is forming; forward rate slows and reverse rate increases. |

|

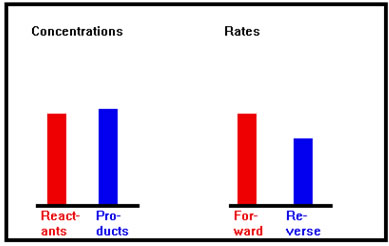

The forward rate continues to decrease as the reverse rate increases; the concentration of the reactants continues to decrease as the concentration of the products increases. |

|

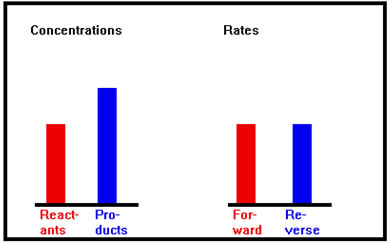

The forward rate is now equal to the reverse rate. When the two rates are equal there is no further change in the concentration of the reactants or products, although both reactions continue, and the system is said to have attained dynamic equilibrium. |

|

As a reaction proceeds, the concentration of the reactants falls. The lower concentration of reactant molecules results in fewer collisions per second and a lower forward reaction rate. If a reaction is very exothermic or endothermic, the temperature will also change. This complication does not affect the basic argument and so, for purposes of this discussion, we will assume that the temperature remains constant. |

|

By the same token, as the concentration of products increases, the number of collisions per second between product molecules increases as well. Since these are the collisions that lead to the reverse reaction, the rate of the reverse reaction speeds up. |

|

Every reaction can theoretically go in reverse simply by having the molecules and atoms reverse their paths. It is not unusual, however, for the reverse of an exothermic reaction to have such a high activation energy that, for all intents and purposes, its rate is zero even when the concentration of products is very high. Such reactions are called irreversible reactions and they not display the characteristics of a dynamic equilibrium.

When the concentrations of reactants and products are such that the two rates are equal, there is no further change in their concentrations and no further change in the rates. The system is in dynamic equilibrium.

|

Since the activation energies of the forward and reverse reactions are different and the probability factors differ as well, equilibrium almost never occurs when the concentrations of reactants and products are equal. If, for example, the forward reaction has a low activation energy while the reverse reaction has a high one, the concentrations of products will have to be much higher than the concentrations of reactants in order for the two rates to be equal. |

Le Chatelier's Principle

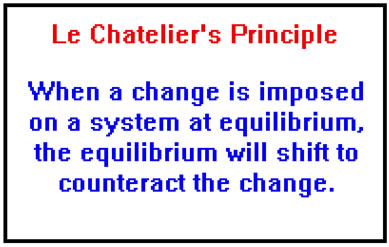

We learned in the previous lesson that Le Chatelier’s principle predicts that when a change is imposed upon a system at equilibrium, the equilibrium shifts in the direction that will counter the change. This principle is predicted nicely by the collision theory of reaction rates.

Collision Theory also explains why, when the equilibrium shifts to undo the change, it can never quite completely succeed. It also makes clear when there will be no response of the system to an externally imposed change.

Concentration Changes

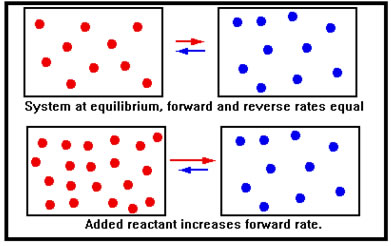

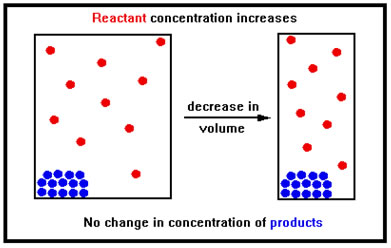

When additional reactant is added to a system at equilibrium, the immediate effect is to increase the concentration of reactant molecules. According to the collision theory, this increases the number of collisions per second of reactant molecules and therefore the rate of the forward reaction.

|

By the same token, there has been no initial change in the concentration of product molecules. Their collision frequency is therefore unchanged and the rate of the reverse reaction if unaffected. In this illustration, we show the reactants and products as if they were in different containers – in reality, of course, they are all mixed together in the same reaction vessel. |

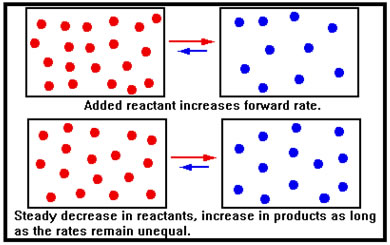

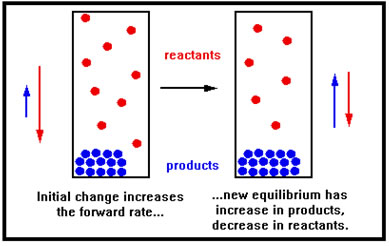

The increase in the forward rate means that the system is no longer in equilibrium and, because the forward rate is now greater than the reverse rate, the concentration of reactants decreases, while that of products increases. In the last lesson, we described this situation by saying that the equilibrium shifted to the right. |

|

As the concentrations change, the forward rate falls, the reverse rate rises, and eventually the two rates become equal – equilibrium is reestablished with some of the added reactant having been converted to product. Because the reverse rate started out at its original value and then climbed as more product molecules formed, the reverse rate at the new equilibrium is higher than the reverse rate at the old equilibrium. This means that the new forward rate must also be higher than its original value, which requires a greater reactant concentration than the original. Thus, though the reaction shifted to remove the added reactant, not all of it was removed. |

|

Temperature Changes

To explain how Collision Theory predicts the effects of temperature changes, there are two additional points we must make first.

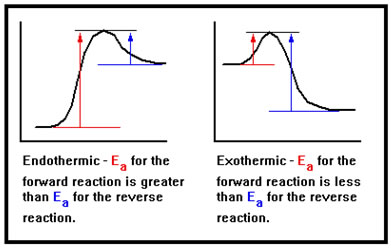

The first is that for an endothermic reaction, the activation energy of the forward reaction must be greater than the activation energy of the reverse reaction. The opposite is true of an exothermic reaction.

|

This comes simply from the requirement that the paths of the forward and reverse reactions are exactly the same, they are just followed in the opposite directions from each other, and the definitions of endothermic and exothermic reactions. |

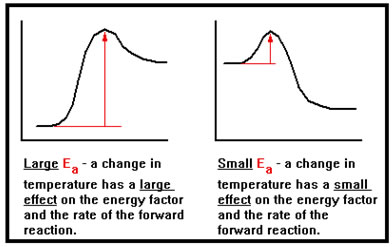

The second is that increasing the temperature has a greater effect on reaction rate for a reaction with a higher activation energy.

|

For example, raising the temperature from 20 to 30 oC for a reaction with an activation energy of 12 kcal/mole increases the fraction of collisions with enough energy to react by 97%. The same increase in temperature for a reaction with an activation energy of only 10 kcal/mol produces only a 75% increase in the fraction of collisions with enough energy to react. |

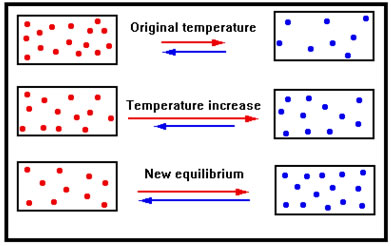

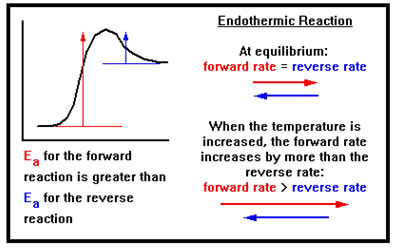

Suppose, now, that we have an endothermic reaction in dynamic equilibrium and we increase the temperature. Because we’ve increased the temperature of both reactants and products, both the forward and reverse reactions speed up.

The temperature change must be applied to both reactants and products – they are mixed together in the same reaction vessel.

Because the reaction is endothermic, however, the forward reaction has a greater Ea than the reverse reaction, so the forward reaction rate increases by more than the reverse reaction rate does.

|

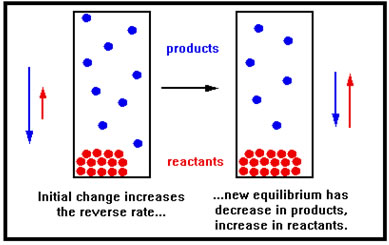

By the same token, if the reaction were exothermic, the activation energy of the reverse reaction would be greater than the activation energy of the forward reaction, and the rate of the reverse reaction would increase more than the rate of the forward reaction would. |

The greater increase in the rate of the forward reaction causes a net formation of products, and a net loss of reactants. These changes in concentration cause the rate of the forward reaction to fall and the rate of the reverse reaction to rise until the two rates are again equal.

As a corollary, because the reaction shifts to the right, and because it is an endothermic reaction, heat is absorbed and the shift therefore causes a decrease in temperature to counteract the initial increase in temperature that was imposed, just as Le Chatelier’s principle predicts.

The bottom line is that you can think of heat as merely another reactant (if the reaction is endothermic) or as another product (if the reaction is exothermic). Raising and lowering the temperature results from adding or removing heat. If you add heat, and endothermic reaction attempts to remove it by shifting to the right, while an exothermic reaction attempts to remove it by shifting to the left.

Pressure Changes

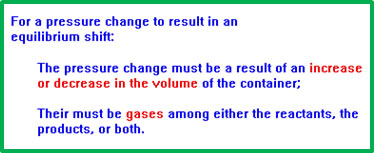

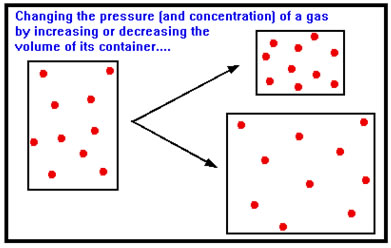

The effect of a change in pressure is subtler still, because whether changing the pressure affects the position of equilibrium or not depends on how we change the pressure.

In particular, if we change the pressure by adding a gas that does not participate in the reaction, there will be no shift. This actually makes sense if you think in terms of ideal gases. In such a mixture, each gas behaves as though it were the only one in the container. Adding an inert gas to an equilibrium has no effect on the concentrations or partial pressures of the gases in the reaction, so it has no effect on the rates of the forward or reverse reaction.

In general, there will be an effect only if we change the pressure by changing the volume of the container and then only if the equilibrium includes gaseous reactants and/or products.

|

Because liquids and solids are highly incompressible, they do not change their volume and therefore they do not change their concentration when the size of the container or the external pressure changes. Thus, if there are no gaseous reactants or products, a change in pressure has no effect on the reaction rates. |

If both of these conditions are met, then reducing the volume squeezes the gaseous reactants and products into a smaller volume, increasing their concentration; while increasing the volume allows them to expand into a larger volume, decreasing their concentration.

|

Again, only reactants and products are affected. Thus, as you might suspect, the eventual effect of changing the volume depends on whether the gases are reactants, products, or both. |

Suppose, for example, that the only gases present are reactants. Decreasing the volume increases the reactant concentration, increasing the rate of the forward reaction, but it has no immediate effect on the rate of the reverse reaction because none of the product concentrations have changed. Since none of the products are gases, decreasing the volume does not change their concentrations appreciably. Because the products are either solids or liquids they are already condensed and they cannot easily be compressed into a smaller volume. And since their concentrations don’t change, neither does the reverse rate. |

|

This increase in the forward rate only causes a net loss of reactant, which slows the forward rate back down, and a net gain in the concentration of product, which increases the reverse rate, until the two rates are once again equal. The shift to the right uses up the gaseous reactant. With fewer moles of gas in the vessel, the pressure falls, countering the initial increase in pressure that resulted from the decrease in volume, just as Le Chatelier’s principle predicts. |

|

If the only gases present are products, then the reverse is true. Increasing the pressure by reducing the volume will cause a shift to the left. And this shift, because it causes a net reduction in the amount of gas in the container, causes the pressure to fall, in accordance with Le Chatelier’s principle. |

|

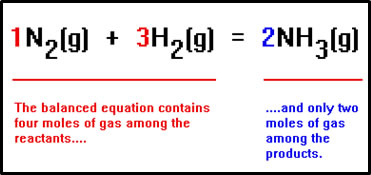

If both reactants and products include gases, the direction of the shift will depend on the relative amounts. In this reaction, since there are more moles of gaseous reactants than gaseous products, reducing the volume will cause the equilibrium to shift to the right.

|

In general, a change in pressure caused by a change in volume has a greater effect on reaction rate than if the number of moles of gas is greater. In this reaction, 4 moles of gas (one mole of N2 and three moles of H2) become 2 moles of gas. Shifting to the right reduces the amount of gas in the vessel, lowering the pressure, and countering the increase in pressure caused by reducing the volume. |

But if we increase the pressure by adding some other gas, one not involved in the reaction, the equilibrium will not shift at all because neither the reactants nor the products will have changed concentration.

|

This assumes, of course, that the other gas does not react with any of the chemicals that are involved in the reaction. If it does, then that will cause a decrease in the concentration of the chemical the other gas reacts with, and this will cause a shift in the position of equilibrium. |

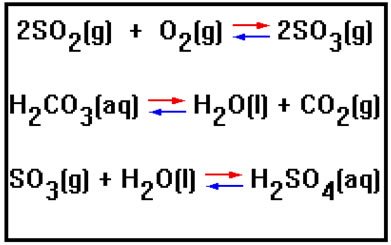

For each reaction shown, decide which direction the equilibrium will shift when the pressure is increased by reducing the volume of the reaction vessel.

(If neither reactants nor products contain any gases, or if the number of moles of gaseous reactants is the same as the number of moles of gaseous products, changing the pressure by changing the volume will have no effect on the position of equilibrium.)

You should have determined the following equilibrium shifts:

First equation: to the right. (There are 3 moles of gas on the reactant side and only two moles of gas on the product side. Shifting to the right will reduce the number of moles of gas, reducing the pressure – counteracting the increase in pressure that was imposed by the reduction in volume.)

Second equation: to the left. (The only gas is among the products. Shifting to the left will reduce the number of moles of gas, and therefore the pressure, counteracting the increase in pressure that was imposed when the volume was reduced.)

Third equation: to the right. (The only gas is among the reactants. Shifting to the right will decrease the number of moles of gas, reducing the pressure, which counteracts the increase in pressure that was imposed when the volume was decreased.)

Side Reactions

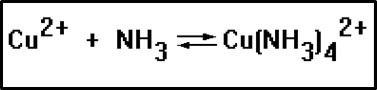

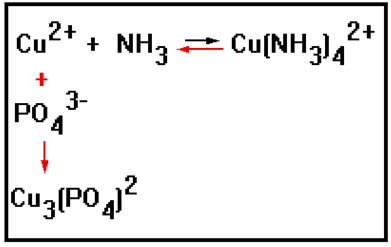

Side reactions can also cause the position of equilibrium to shift. For this reaction, for example, adding a little sodium phosphate, Na2PO4, causes the equilibrium to shift to the left.

The copper-ammonia complex is deep blue in color. When phosphate salts such as sodium phosphate are added to the reaction mixture, the color fades, indicating a reduction in the concentration of the blue complex and therefore a shift to the left.

This is caused by a side reaction. The phosphate ion reacts with the copper(II) ion to form insoluble copper(II) phosphate. The resulting reduction in the concentration of copper ions causes the forward rate to fall, and there is a net shift to the left that results.

You’ll find another example of side reactions in the second lab exercise for this lesson. As in this example, one of the products in the reaction you will study is strongly colored, so that you can follow the shifts in equilibrium by following the increase or decrease in color intensity as you change various conditions.

In the next page of the lesson, you’ll learn how to calculate the concentration of reactants and products that occur when reactions attain equilibrium.

At this point you should be able to do all but the last problem in the problem set for this lesson. Before moving on, it might be good to try them.