Lesson 8: Enthalpy

Most chemical reactions involve the absorption or the release of energy. When a candle burns, for example, energy is released in the form of heat and light.

Energy can also be released in other forms. The chemical reaction in a battery releases energy in the form of electricity. And some reactions absorb energy rather than release it. Chemicals on the surface of photographic firm, for example, absorb light energy as they react to produce the image on the film.

We will be concerned only with the release and absorption of heat.

Enthalpy | Heat of Reaction Calculations | Answers to Exercises 5 & 6

Enthalpy

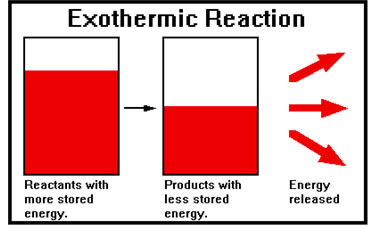

When energy is released in a reaction, the products of the reaction must end up with less stored energy than the reactants had. Such a reaction is called an “exothermic” reaction because heat “exits” the chemicals in the course of the reaction.

|

You can detect most exothermic reactions because the heat they release causes the temperature to increase. The most familiar exothermic reaction is probably combustion. When combustible materials combined with oxygen, heat is released and the temperature of the burning materials increases. Usually the heat is sufficient to cause the gaseous products to glow. These hot, glowing gases are what we perceive as a flame. |

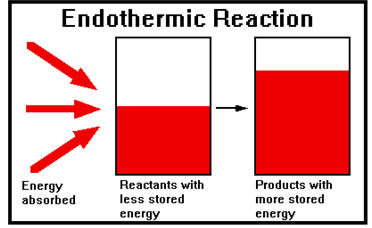

When energy is absorbed, the products end up with more stored energy than the reactants. This kind of reaction is called an “endothermic” reaction because heat energy “enters” the chemicals in the course of the reaction.

|

Endothermic reactions are less common than exothermic ones. One you may have seen occurs inside portable ice packs used in athletics. When the ice pack is activated, a chemical reaction occurs that absorbs energy, and the temperature of the chemicals falls, cooling the injury. Another endothermic reaction occurs when you charge a battery. Electrical energy is absorbed (and stored for later use) when a battery is connected to a charger. |

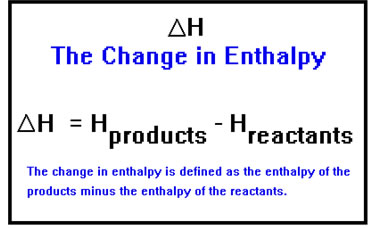

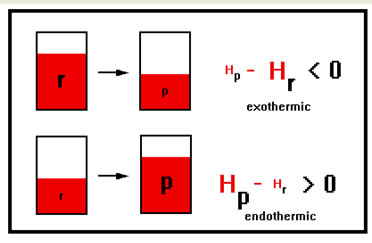

Energy that is stored in chemicals is called “enthalpy” and it’s given the symbol H. During the course of a reaction, the enthalpy content of the chemicals changes as the atoms and the molecules rearrange themselves from reactants into products. This change in enthalpy content is given the symbol ∆H.

Stored energy does not affect the temperature of a chemical. Only when the energy is converted from its stored form into heat does the temperature rise. And, of course, when energy is converted from heat into its stored form, the temperature falls. TNT (tri-nitro toluene) and nitroglycerine are examples of chemicals in which there is a great deal of stored energy. They are normally at room temperature, but when they react….

The exact definition of ∆H, the enthalpy of the products minus the enthalpy of the reactants, means that when energy is released, ∆H is a negative number and when energy is absorbed, ∆H is a positive number.

|

This definition means that what we have called ∆H reflects the change in energy content of the chemicals undergoing the reaction. When the chemicals lose energy (it is releases), ∆H is negative, that is, their energy content undergoes a negative change. We use the same convention talking about money: when we lose money (it's released?) we describe the loss as a negative cash flow. |

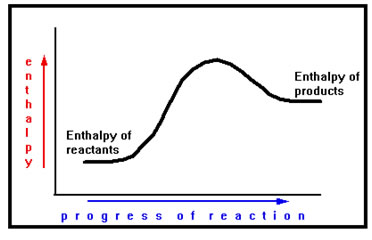

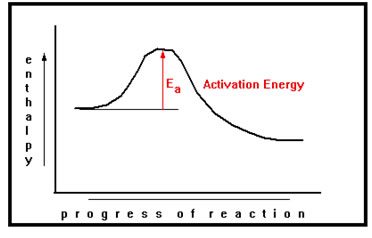

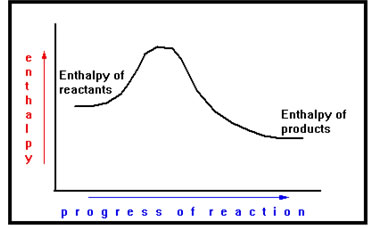

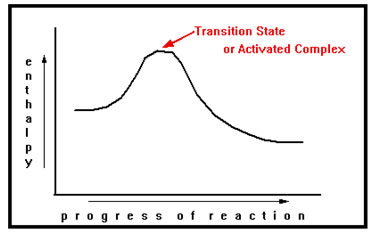

We can represent the energy changes associated with a reaction with a “reaction diagram.” This diagram shows that change in stored energy, that is, how the enthalpy changes, as the reaction progresses.

|

Reaction diagrams are rarely labeled. They are qualitative rather than quantitative. In other words, they show whether energy is being released or absorbed without showing exactly how much. As we see, they nevertheless give a significant amount of useful information about the reaction. |

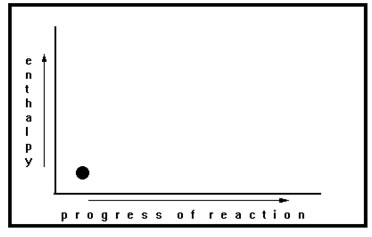

The horizontal axis represents the course of the reaction. Reactants are located on the left end of the axis while products are on the right. The vertical axis slows the amount of stored energy they have. The dot on this graph represents reactants with relatively low enthalpy. The single dot represents all of the reactants and the total amount of energy they have stored. Its position on the left hand side of the graph indicates that the reaction has not yet begun. Its position toward the bottom of the graph indicates that the reactants have a relatively low amount of stored energy. |

|

As the reaction proceeds, the dot moves to the right. When it reaches the right side of the graph, it represents the products. Its movement from left to right represents the reactant atoms and the molecules in the process of rearranging themselves – reacting – to become products.

This is obviously an oversimplified representation of most reactions. But since all we are interested in is the difference in enthalpy between the reactants and the products, we need not specify the nature of the chemicals involved at all.

Rather than a moving dot, we use a line to indicate the path the reaction takes. In this reaction, the products have a greater enthalpy content that the reactants did. This reaction is therefore endothermic and its ∆H is positive.

The atoms involved in this reaction have more stored energy when they are in the form of products than they did when they were in the form of reactants – their enthalpy content has increased.

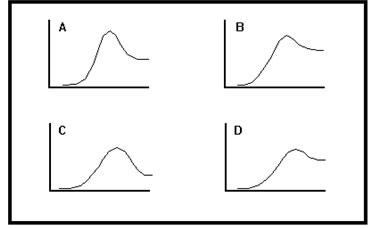

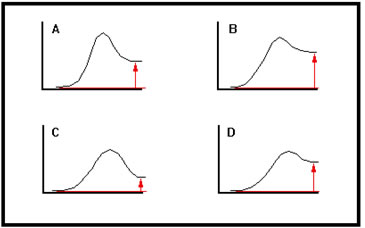

Here are reaction diagrams for several endothermic reactions. The amount of heat absorbed is equal to the difference in height between products and reactants. Which of these reactions is the most endothermic? Which is the least endothermic?

|

|

|

|

Here is a diagram for an exothermic reaction. In this case, the enthalpy of the products is less that that of the reactants. The resulting change enthalpy is negative.

|

In this reaction, energy is released. The atoms have more stored when they are arranged in the form of reactants than they do when they are in the form of products. |

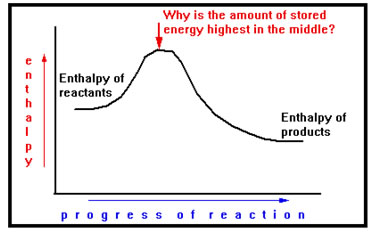

Each of the reactions diagrams we have seen has a high spot in the middle where the stored energy is greater than either reactants or products. To understand why, we need to know how energy is stored in chemicals.

|

What the hump in this diagram implies is that before energy can be released in this reaction, first a small amount of energy must be absorbed. An illustration of that is a common match. It burns and releases energy, but not spontaneously, first you must supply a little energy – in this case, the heat generated by the friction of rubbing it against the striker on the matchbook. |

When the atoms in a reaction “rearrange” in going from reactants to products, they break existing chemical bonds and form new ones.

{Not every reaction involves both breaking old bonds and making new ones. A few involve only one of these. However, we will talk about the most general – and most common – case, reactions in which both bond making and bond breaking occur.}

Breaking a chemical bond requires energy. When energy is absorbed in a chemical reaction, this is where it goes. By the same token, the formation of a chemical bond releases energy. In an exothermic reaction, this is where the released energy comes from.

|

It shouldn’t be surprising that breaking a bond, of any kind, requires an input of energy. Imagine the bond between two strong magnets, for example: you have to work pretty hard to get them apart. What is less obvious is that forming a bond releases energy. Think of the magnets again. If they are close enough to attract each other, they will pull your hands together as they bond – doing work (another form of energy) on you in the process. |

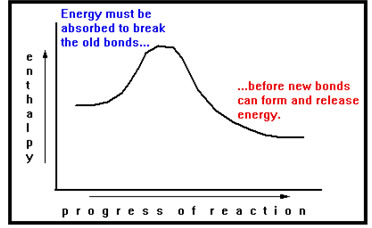

Before the atoms in a chemical reaction can form new bonds, they must first break their existing bonds. Thus, a chemical reaction must start with the absorption of energy.

|

Actually, the old bonds do not have to be completely broken before new bonds can start forming. It is true, however, that the old bond must start breaking before the new bonds can start forming. Energy is therefore being absorbed and released at the same time. The balance between these two processes determines the exact path of the reaction diagram. |

The exact arrangement of the atoms, somewhere between reactants and products, at which the amount of stored energy is a maximum, is called the transition state of activated complex.

|

The structure of the activated complex is often difficult to determine because the atoms adopt this arrangement only in passing. Often we must guess as to the exact arrangement, but is typically involves old bonds which are partially broken and new bonds which are partially formed. On the other hand, it is relatively easy to measure experimentally the energy of the transition state. |

The amount of energy that must first be absorbed to reach the activated complex is called the activation energy, Ea. As we will see, the value of the activation energy plays a major role in determining how fast the reaction goes.

|

We’ll deal with the factors affecting reaction rates in the next page of this lesson. To anticipate a bit, however, it should not surprise you that the more energy that must first be absorbed, the slower the reaction.

Heat of Reaction Calculations

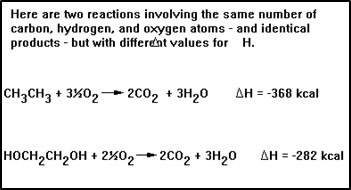

The exact amount of heat absorbed or released in a reaction depends, of course, on what the reaction is. Some reactions are more or less endothermic – or more or less exothermic – than others.

The exact value of ∆H depends on the relative strength of the bonds that are broken and the bonds that are made. Exothermic reactions typically involve breaking weaker bonds and forming stronger ones. Endothermic reactions involve breaking stronger bonds and forming weaker ones. Another factor that enters into the mix is the number of bonds being formed compared to the number being broken. Often it is possible to calculate the enthalpy change for a reaction from knowledge of the kind and number of bonds broken and formed.

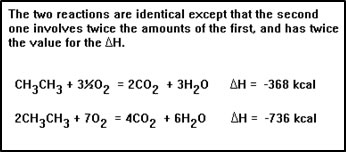

For a given reaction, the amount of heat involved depends on the amounts of chemicals. In fact, it is directly proportional to the amounts of reactants and products present. Therefore we can calculate the amount of heat absorbed or released in a reaction just like we can calculate amounts of reactants used and products formed.

|

Notice that doubling the amounts of reactants and the products also doubled the amount of heat released. Since we have to maintain a balanced equation, all reactants and products must increase (or decrease) by the same factor. Increasing (or decreasing) the value of ∆H by this factor preserves the balance between the amounts of chemicals and the amount of heat. |

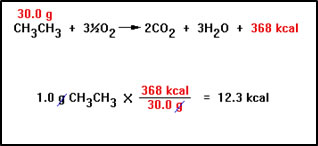

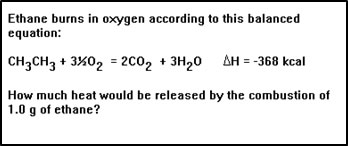

Problems involving enthalpy changes can be worked in exactly the same way that we worked stoichiometry problems. Suppose, for example, that we want to know the amount of heat that would be produced by burning 1.0 g of ethane in oxygen.

|

As with stoichiometry problems, there are many possible variations. For example, we might have asked how much heat is released when 2.5 g of CO2 are formed: or how many grams of ethane would have to be burned to supply 100 kcal of heat. We might even have asked a limiting reagent question: how much heat is released when 5.0 g of ethane react with 15.0 g of oxygen? |

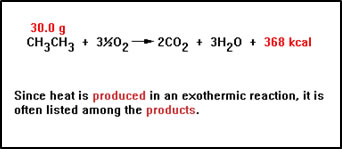

The balanced equation tells us that burning 1 mole of ethane releases 368 kcal of heat. Since the molecular weight of ethane is 30.0 g/mol, the balanced equation also tells us that burning 30.0 g of ethane produces 368 kcal of heat. |

|

|

It may help to keep things clear if you list the energy released in an exothermic reaction among the products (because heat is produced) and the energy absorbed in an endothermic reaction among the reactants (because the heat is “used up”). |

As before, we use the relationship the balanced equation gives us between the mass of ethane burned and the heat produced to construct a “conversion factor” that gives the amount of heat produced for any mass of ethane burned.

|

In a sense, “kcal” is just another product in the reaction and the 368 is its coefficient in the balanced equation. In the end, this is just another stoichiometry problem with heat as a product. |

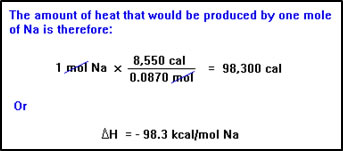

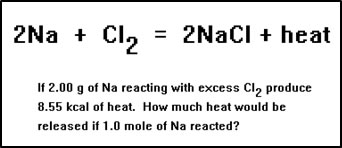

Here’s another example. Suppose that when 2.00 g of Na react with excess Cl2, 8,550 cal of heat are released. How many kcal would be reacted when 1.0 mol of Na reacts?

|

The “heat of reaction” is the amount of heat absorbed or release when the amounts of reactants in the balanced equation (usually one mole of the main reactant) react. In this problem, we are being asked for the heat of reaction of sodium and chlorine, expressed in kcal per mole of sodium. |

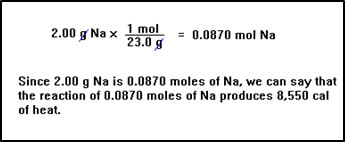

Since we know that 2.00 g of Na produce 8,550 cal of heat, we can use this as our relationship between the amount of sodium that reacts and the amount of heat produced. But since the problem refers to one mole of sodium, we must first convert from grams to moles. |

|

|

We might also have simply reworded the problem to ask how much heat is released when 23.0 g (the mass of one mole) of sodium reacts. |

We can now set up the problem just like a stoichiometry problem. We add the negative sign to the final answer because we know the process is exothermic – heat is released.

|

Several additional examples of this type of problem are given in exercise 4 in your workbook. In each case, two different methods are shown, depending on whether you know the ∆H per mole of Na, or the amount of heat involved in the balanced equation (which includes two moles of Na).

Exercises 5 and 6 in your workbook provide some practice problems for you to try. Be sure to work these before you move on to the next part of the lesson.

Answers to Exercise 5 & 6

5. Calculate DH for each of the following reactions. Be sure to show sign (positive or negative) and per mole of which chemical.

a. When 0.070 mole Al is oxidized 28 kcal of heat is released.

DH = - 400 kcal/mole of Al

b. When 20.0 g of MgCl2 is converted to Mg and Cl2, 32.2 kcal of heat is required.

DH = +153 kcal/mole of MgCl2

c. When 0.335 g of K reacts with excess Cl2 to make KCl, enough heat is released to change the temperature of 360 g of water from 18.0 oC to 19.3 oC.

DH = - 54.6 kcal/mole of K

6. Use the information in Example 2a to answer the following questions.

a. How much heat is released when 6.0 mole CH4 is burned?

1300 kcal (1278 kcal)

b. How much heat is released when 4.2 g CH4 is burned?

56 kcal

c. How much CH4 must be burned to provide 55 kcal of heat?

0.26 moles of CH4

d. A person wants to heat the water in a hot tub (320 kg) from 70°F (21°C) to 100°F (38°C) using a natural gas (mostly CH4) burner. Assuming all the heat from the reaction goes into the water, how much CO2 will be put into the atmosphere?

26 moles of CO2 (you determine the number of kcal released in the reaction by using the q = m x c x DT equation from lesson 2)