Lesson 2: Condensed Phases

Take a quick look around. Most of the things you see, though and interact with are solids. Each is different, and all have distinct, characteristic properties.

The properties of solids make them the most useful of the three common phases of matter. For any particular purpose, you can choose a solid of the appropriate hardness, strength, electrical conductivity, transparency, thermal conductivity, appearance, shape and so on.

In this lesson we will be interested in only a few of the properties of solids some of which all solids share, and some which vary from one solid to another. We will also be interested in the properties of the other “condensed” phase of matter, liquids.

Solids | Liquids | Intermolecular Attractions

Solids

All solids have some properties in common.

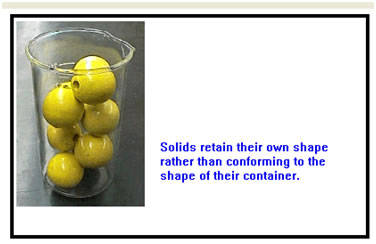

They have a (more or less) permanent shape. Unlike liquids and gases, solids do not assume the shape of their container. |

|

Of course, it is easier to change the shape of some solids than it is others. Soft solids can be bent, metals can often be pressed, pounded, or drawn into specific shapes, and many solids can be drawn into specific shapes, and many solids can be cut or otherwise shaped. But if you have a sample of a solid material, that sample has a definite shape.

Even powders have this characteristic - each individual grain has a shape which it maintains unless it is acted upon by some external force.

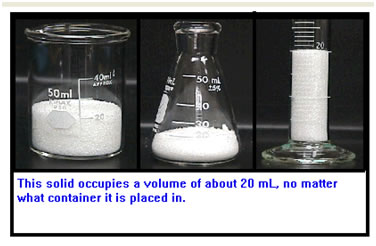

All solids have a definite volume. While a gas expands to fill its container, a solid’s volume is the same no matter what container, if any, it’s in. |

|

We don’t mean, of course, that a particular kind of solid has a particular volume (or shape) associated with it. There is no characteristic volume for iron, for example.

The point is that for any given sample of a solid, the volume of that sample does not depend on the container that it is in. The point is that for any given sample of a solid, the volume of that sample does not depend on the container that it is in. And while it can change with such things as temperature, even those changes are relatively small.

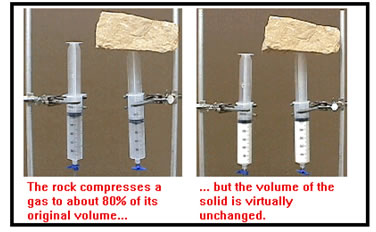

Solids are also very difficult to compress. It’s easy to squeeze a gas into a smaller volume, but it takes enormous pressure to make even a small difference in the volume of a solid. |

|

There are some solids that seem to be easily compressible. Foam rubber, for example, the stuff of which Nerf balls are made, and sponge, are two materials that are easy to squeeze into a smaller volume, but such solids consist of a latticework of solid material surrounding many small air cells. When you squeeze a Nerf ball of a sponge, you are basically squeezing out the air. Other solids that seem compressible – a rubber eraser, for example, are in fact, not being compressed, they are just being deformed.

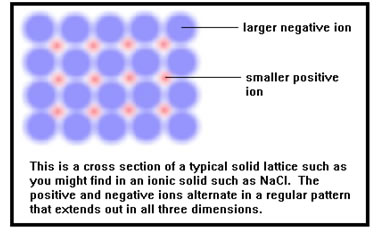

Solids consist of atoms (or ions or molecules) bonded close together in a regular array. Solids are incompressible because there is almost no empty space between their atoms. They have a fixed shape and volume because the atoms are held tightly together in the solid array. |

|

There are a few solids in which the atoms or molecules, while still bonded to one another, are not in a regular array. In glass for example, the silicon and oxygen atoms are irregularly arranged with no long range order to their structure. Even so, because the atoms are all bonded tightly to neighboring atoms, glasses have the same general properties as other solids do.

Liquids

The common properties of liquids are intermediate between those of solids and gases.

Liquids are, in fact, a rather unusual form of matter. They only exist where there is significant external pressure. One way to think of a liquid is that it is a gas which has been compressed until the molecules (or atoms) are touching one another.

In fact, if the external pressure is low enough, heating a solid won’t cause it to melt. Instead, it will sublime – that is, it will change directly from a solid to a gas. Dry ice (solid carbon dioxide) is an example of a solid for which atmospheric pressure is not sufficient to cause it to form a liquid. Solid carbon dioxide, when heated, converts directly to a gas, hence the name “dry” ice.

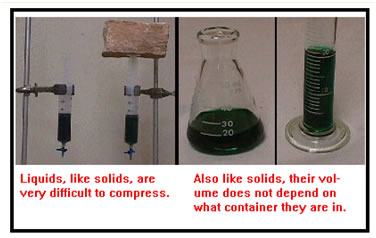

Like solid, liquids are very difficult to compress. And also like solids, liquids have a fixed volume – they don’t expand to fill their container. |

|

Because the molecules or atoms are essentially touching one another, compressing a liquid is very had to do.

Liquids do not expand to fill their container essentially because the pressure of the air acts like an internal “lid.” In fact, as we will see, some of the liquid molecules do escape – the “lid” is rather porous.

But like gases, liquids flow and so they do assume the shape of their container. At least, they assume the shape of the bottom of their container. (Unlike gases, they don't expand to fill the whole container.) |

|

Like those of a solid, the molecules of a liquid are very close together – there is almost no empty space between them – that’s why liquids are incompressible and occupy a fixed volume. |

|

In most liquids, the molecules are slightly farther apart than they are in the solid. As a result, for most materials, the density of the solid is usually higher that the density of the liquid at the same temperature.

One unusual and notable exception is water. On the average, water molecules are closer together in liquid water at 0 than they are in solid ice at the same temperature, so ice is less dense than water. As a result, ice floats. If this were not so, lakes and streams and the arctic oceans would freeze from the bottom up and fish could not survive the winter.

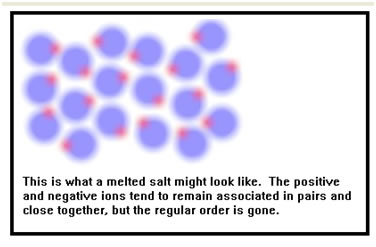

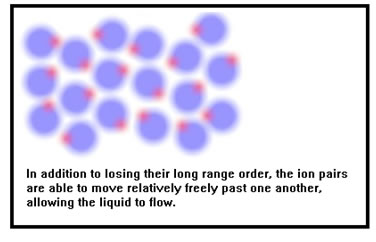

But the molecules of a liquid are energetic enough that they do not stick together. Like the molecules of a gas, they can move past each other a little like people in a very crowded room, so liquids flow. In a sense, liquids behave like very very fine powders whose “grains” contain on the order of eight to ten molecules. In fact, some very fine powders appear to flow just like liquids if the grains are not too “sticky.” Finely powdered Teflon, for example, looks very much like milk. |

|

Intermolecular Attractions

Virtually all of the rest of the properties of a liquid or a solid – including pressure and volume – depend on what the liquid or solid is and on the nature and strength of the attraction between the molecules. (This is significantly different from the behavior and properties of gases. Recall from Lesson 1 that the pressure and volume of a gas do not depend on the identity of the gas; according to the KMT, particles of an ideal gas behave independently of one another, with no attractions between the particle.)

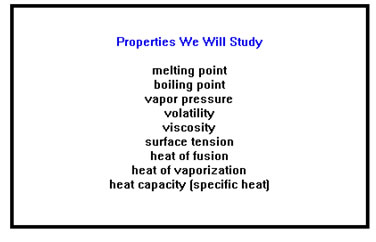

We are concerned here with physical properties like melting and boiling points, viscosity, vapor pressure, density, volatility, and so on. The chemical properties of all phases of matter depend on the atomic and molecular structure of the material. |

|

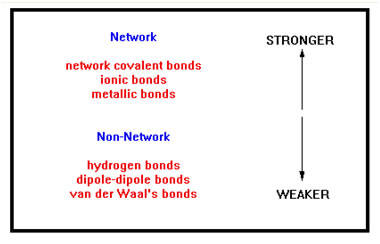

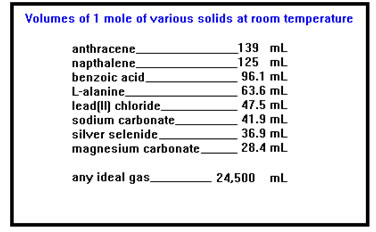

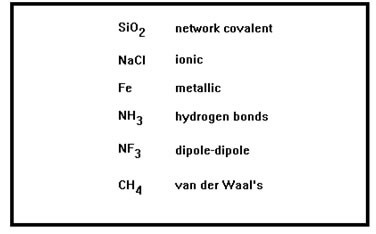

In Chemistry 104 you learned that there are a variety of different types of bonds, ranging from very strong network covalent bonds to very weak van der Waal’s bonds.

The first three types of bonds listed – network covalent, ionic, and metallic, tend to be rather strong. Materials in which these types of bonds are present tend to be solids at room temperature. The rest (hydrogen bonds, dipole-dipole bonds, and van der Waal’s bonds) tend to be much weaker and materials whose intermolecular bonds are of one of these types are usually liquids or gases at room temperature.

You also learned how to determine, from the structure of a compound, just what kinds of bonds are present.

|

To review very briefly, quartz (silicon dioxide) and pure carbon (diamond and graphite) have network covalent bonds. Compounds that consist of both metal and non-metal atoms have ionic bonding. Materials that consist of only metals have metallic bonding. Covalent compounds have one of the remaining three types of bonds. Compounds in which one or more hydrogen atoms are bonded to either a nitrogen, oxygen, or fluorine atom have hydrogen bonds. All other polar compounds have dipole-dipole bonds. Non-polar compounds have van der Waal’s bonds. |

In the next two sections of this lesson, we will study some of the properties of liquids and solids. We will also learn about heat and how to relate an amount of heat energy to an amount of a material whose temperature or phase changes.

Before going to the next lesson, it’s important that you have a clear picture in your mind of what solids, liquids, and gases look like on an atomic scale. If you have questions regarding these concepts ask them now by calling or e-mailing your instructor or by stopping into the lab to talk with the instructor on duty there.

Then, in the last part of this lesson, we will correlate the strength of the attraction between molecules or atoms in a liquid or a solid to the magnitude of some of the properties we have studied.

We will try to predict, for example, which of two materials has the higher boiling point, or the lower viscosity, or the higher vapor pressure, or the lower volatility, based on which of the two has the stronger (or the weaker) intermolecular bonding.

As we mentioned in the introduction, if you need to do so, you can review the lessons on intermolecular bonding from CH 104 online. (See Ex. 1 & 2 in your workbook for this lesson, as well.)