Lesson 2: Intermolecular Bonds

In this final section of Lesson 2, we'll take a look at how the process of breaking bonds (or forming bonds) requires (or releases) heat. Then we'll take some time to examine how the strength of intermolecular bonds relates to some observable physical properties, such as viscosity and vapor pressure.

Chemical Bonds & Heat | Intermolecular Bonds & Physical Properties

Chemical Bonds & Heat

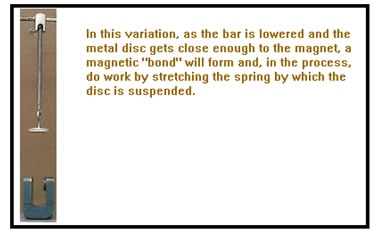

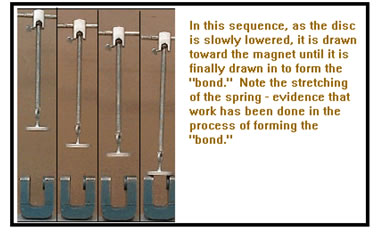

Forming a chemical bond releases energy. You can see this for yourself if you happen to have a strong magnet handy. Hold the magnet in one hand close to a piece of ferrous metal (or the opposite pole of a second magnet) in the other.

Ferrous metals are those containing iron. Most kinds of steel will work just fine, but stainless steel, such as is used to make kitchen utensils, won’t.

Take care if you do this at your computer. Magnets stong enough to be effective will erase data on computer disks if they get too close.

When the magnet and metal get close, they are attracted to one another and they actually pull your hands together. In sticking together – forming a bond – they do work on your hands that you can feel.

|

|

Magnetic force drops off rather quickly with distance, so you will have to get the magnet fairly close to the metal (or other magnet) to feel the effect, particularly if you have a weak magnet. However, if you are careful, you should be able to feel the effect.

There are magnets available in the lab if you would like to try this demonstration there. (See Ex. 3 in your workbook as you do this demonstration.)

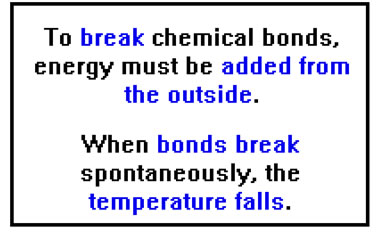

By the same token, breaking a bond requires that energy be added to the system. In the case of the magnets, breaking the “bond” between them requires that you add energy to the system in the form of work. |

|

If you found a reasonably strong magnet, it may seem that you have to do considerably more work to separate the magnets than they did on you in sticking together. Actually, the amount of work is identical. To see this, try to hold the magnets very close together without letting them from a “bond.”

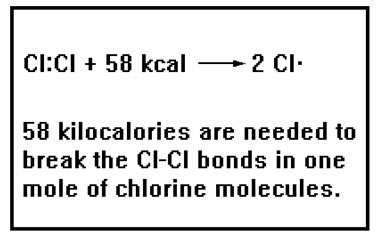

When, instead of magnetic bonds, chemical bonds are formed, energy is also released and it causes the molecules to move faster. This motion is what we call heat. What we observe is that the temperature of the material rises. |

|

Here is a rough analogy. Imagine two strong magnets close enough to attract one another. The attraction causes them to accelerate towards one another and stick together. As a result of the acceleration, the magnets are now moving faster than before and this additional kinetic energy is analogous to the heat released when chemical bonds form.

The amount of heat that is released when bonds form depends on the strength of those bonds - the stronger the bond, the more heat is released. In our analogy, the stronger the attraction of the two magnets, the more they accelerate towards one another and the great the resulting motion. In the case of the magnet, most of the energy would be lost to friction. At the molecular level, there is no friction. |

|

Similarly, if we want to break chemical bonds, we add energy also in the form of heat. The molecules speed up, the temperature rises, and the bond begin to break as a result of the more violent collisions between molecules. When chemical bonds break, energy is absorbed and the temperature falls. This is why, when water evaporates from your skin, it feels cool: the bonds holding the water molecules together, break and heat is absorbed from your skin. |

|

If you want to force bonds to break, however, you must add energy from an outside source. If you add it as heat, the temperature will rise, but some of the heat energy will be absorbed as the bonds break and so the temperature will not rise as much as if no bonds had broken.

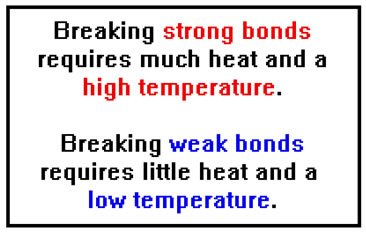

The amount of heat we must add to a system to break bonds also depends on the strength of the bonds. The stronger the bonds, the more heat energy we must add to break them and, consequently, the higher the temperature. |

|

In any collection of molecules, there are always some moving much faster than average and some moving much slower than average. Even at low temperatures some molecules will collide hard enough to break bonds and even at high temperatures some collisions will not be violent enough to break bonds. We say, however, that the temperature is sufficient to break bonds when the average collision is of sufficient energy to do so.

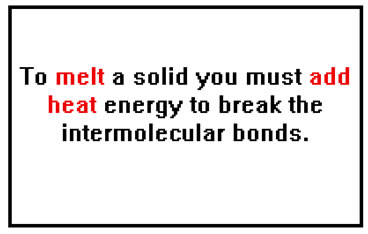

Melting a solid requires that we break some of the intermolecular bonds, so it makes sense that we must add heat, and raise the temperature, of a solid to melt it.

|

It may seem surprising that the melting point is so well defined. It seems to make more sense that the solid should soften and melt over a range of temperature rather than all of a sudden at a specific melting temperature. It turns out that the melting point is defined by the vapor pressures of the solid and the liquid. At the melting point they are equal. Above the melting point the vapor pressure of the liquid is lower and below the melting point the vapor pressure of the solid is lower.

|

Try to answer the questions in Ex. 4 before you move on; the answers are just below.

Answers to Ex. 4:

a. A

b. exothermic

c. release

d. B

e. endothermic

f. use

Intermolecular Bonds & Physical Properties

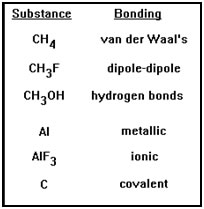

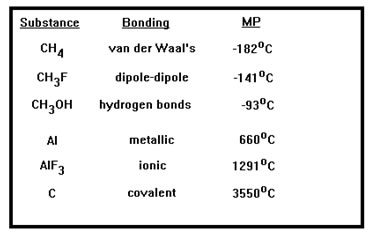

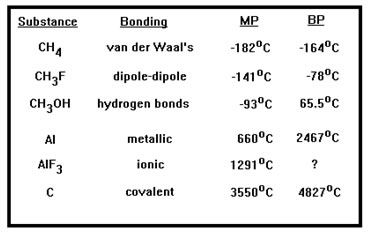

On your screen are six substances – with six different intermolecular bonding types – listed in order of bond strength. Which of these would you expect to have the highest and lowest melting points? |

|

Since melting a solid requires that some of the intermolecular bonds be broken, it makes sense that the stronger those bonds, the greater the energy – and the higher the temperature – that’s required.

|

Not only do the melting points reflect the order of the strength of the intermolecular bonds, they reflect the relative magnitudes as well. The three materials at the top of the list have relatively weak intermolecular bonds and also show quite low melting points. The three materials at the bottom of the list have relatively strong network bonding and also have much higher melting points. |

If you were to look at many compounds of all of these types, you would find considerable overlap: not all network covalent compounds have higher melting points than all ionic or even metallic materials, nor do all hydrogen bonded materials have higher melting points than all dipole-dipole or even van der Waals bonded materials. These are general trends that assume other factors, such as molecular size and shape, are similar.

Other factors also influence melting points, so the correlation is not perfect, but in general, the stronger the intermolecular bonds, the higher the melting point of a material. The same can be said of boiling points as well. |

|

For example, titanium, which is metallic, melts at 1675 oC while natural quartz, silicon dioxide, a network covalent material, melts at only 1610 oC.

Similarly, the alpha form of sulfur trioxide, a nonpolar compound, melts at around 62 oC while water, which is capable of hydrogen bonding, melts at 0 oC.

There are several other properties of solids and liquids that are related to the strength of intermolecular bonds. They include viscosity, surface tension, volatility, and vapor pressure.

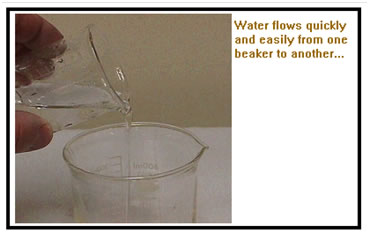

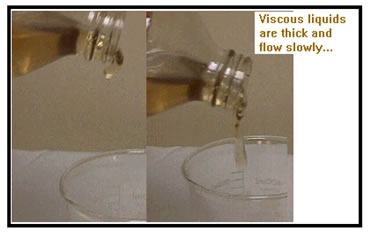

Viscosity is the resistance to flow. Liquids with low viscosity, like water, flow easily. Liquids with high viscosity, like motor oil or syrup, flow only slowly. The more strongly the molecules are attracted to one another, the more they resist flowing past one another, and the higher the viscosity.

Viscosity is a sort of internal friction and is measured in a unit called a “poise.” Values of viscosity among ordinary liquids at room temperature range from about 15 poise for glycerin to about 0.002 poise for diethyl ether. Viscosities of other common liquids are as follows: 0.84 poise for olive oil, 0.012 poise for ethyl alcohol, and 0.010 poise for water.

Viscosity varies considerably with temperature as well. Water’s viscosity, for example, is 0.018 poise at its freezing point and 0.0028 at its boiling point – a sixfold difference. The viscosity of olive oil increases from 0.84 poise to 1.4 poise if the temperature falls a mere ten degrees.

Viscosity is also affected by the shapes of molecules. Molecules that are long and ‘stringy’ get tangled up and this also causes resistance to flow. This is one of the reasons that oil has high viscosity. The molecules consist of long chains of 15 or more carbon atoms.

A great deal of research has gone into designing motor oils that maintain a uniform viscosity over a broad range of temperatures. Modern “multi-grade” motor oils (with designations like 10W-30 or 20W-50 based on standards developed by the Society of Automotive Engineers, the SAE referred to on the label of oil bottles) are the result of that research.

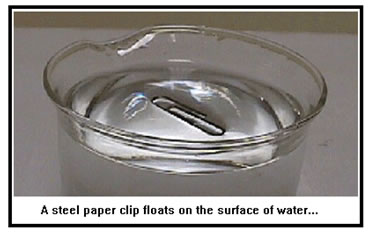

Surface tension is the resistance of the surface of a liquid to being broken. It is caused by the fact that the molecules on the surface of a liquid are not bonded to as many neighboring molecules as those beneath the surface. As with viscosity, the greater the attraction between molecules, the higher the surface tension.

|

Any action that breaks the surface of a liquid must first distort the surface and therefore increase the surface area. Because molecules on the surface of a liquid are bonded to fewer neighboring molecules (there are none above them), increasing the surface area necessarily involves breaking some intermolecular bonds. An object will break the surface of a liquid only if it exerts a force (due to gravity, momentum, etc.) that is greater than the force of the intermolecular bonds that must be broken. |

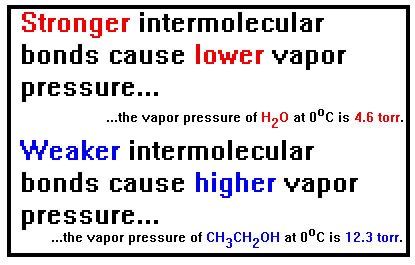

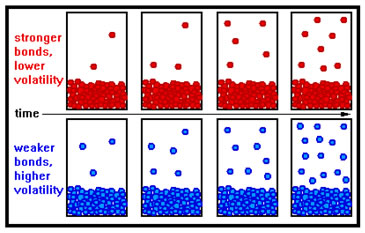

Volatility and vapor pressure really measure the same phenomenon. Volatility is the tendency of a liquid to evaporate and, as you might expect, the stronger the intermolecular bonds, the less the tendency to evaporate and the lower the volatility. |

|

Volatility and vapor pressure are two properties that increase in value as the strength of intermolecular bonds decreases. Most physical properties (boiling point, melting point, viscosity, and surface tension, for example) correlate directly to the strength of intermolecular bonds – increasing in value as the bond strength increases. It might be a good idea to commit that distinction to memory.

If a liquid is placed in a closed container, it will tend to evaporate. The more volatile it is, the more rapidly it will evaporate. It is also the case that raising the temperature of the liquid will cause it to evaporate more rapidly. |

|

At any given temperature the molecules in a liquid have a broad range of kinetic energies – some are very high, some are very low, but most are close to the average. To escape from the liquid, a surface molecule must have sufficient kinetic energy to overcome the intermolecular bonds holding it to its neighbors. The higher the temperature, the greater the fraction of surface molecules that will have this amount of energy and the greater the rate of evaporation. Further, at any given temperature, in a liquid whose molecules are held together by weak intermolecular bonds, a relatively larger fraction of the surface molecules will have sufficient kinetic energy to overcome those bonds than in a liquid whose molecules are held together by strong intermolecular bonds.

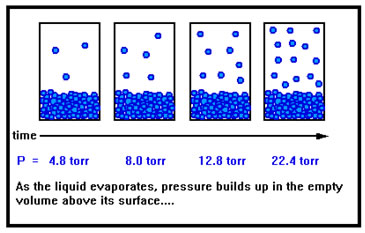

As the liquid evaporates, gas begins to accumulate in the empty volume above the liquid, and this gas exerts a pressure against the walls of the container. As more liquid evaporates, the pressure increases. |

|

Recall from the ideal gas law that the pressure is determined by the volume, temperature, and number of moles of gas present. As the liquid slowly evaporates, the volume of the space above the liquid remains the same as does the temperature. But the number of moles of gas slowly increases, increasing the pressure.

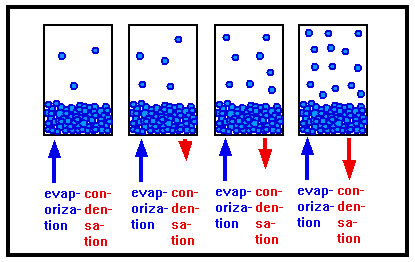

The gas above the liquid can condense back into the liquid. The rate at which this happens depends on how much gas there is – in other words, the more gas, and the higher the pressure, the greater the rate at which the gas condenses back to the liquid phase. |

|

The molecules now in the gas phase above the liquid are in constant motion and strike each other, the walls of the container, and the surface of the liquid. Those that strike the surface of the liquid often “stick,” attracted by the intermolecular forces that held them in the liquid in the first place, and recondense into the liquid phase. The rate at which this happens depends mostly on how many such collisions take place, which in turn depends on the number of gas molecules there are above the liquid. This number also determines the pressure the gas exerts, hence, the rate of condensation increases as the pressure increases.

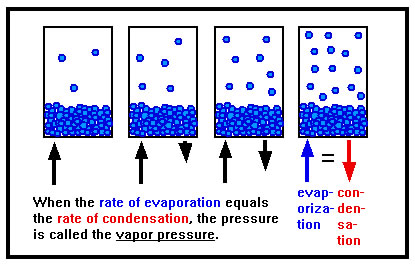

As liquid evaporates, and the amount of gas present increases, the rate of condensation also increases. Eventually, the rate at which the gas condenses is the same as the rate at which the liquid evaporates. When this happens, the pressure of the gas stops changing. This constant pressure is called the vapor pressure of the liquid. |

|

This situation is an example of what is known as “dynamic equilibrium.” The overall state of affairs doesn’t change: the amount of gas above the liquid and therefore the pressure it exerts remain constant. But this equilibrium is dynamic because it results from two ongoing but opposing actions that happen to exactly balance each other out.

It is the same idea as if you were running 10 miles per hour on top of a long train of flat cars moving north at 10 miles per hour. You would, in effect, be stationary, even though you were moving.

What determines the vapor pressure of a particular liquid? One factor is its volatility. A more volatile liquid evaporates more rapidly, so more gas must be present above the liquid, exerting a greater vapor pressure, for the rates of evaporation and condensation to be the same. (At this point we are, of course, describing the same factors that influence volatility.) |

|

As we have seen, the weaker the intermolecular bonds, the greater the volatility and, consequently, the greater the vapor pressure.

At room temperature, the vapor pressure of water, for example, is just little over 20 torr, not very high. Yet, if water is left in an open container, where the pressure cannot build up, the rate of condensation will never equal the rate of evaporation and the water will eventually all evaporate.

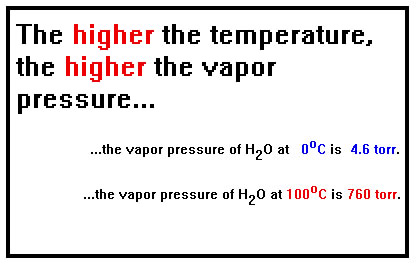

The other factor is the temperature. The higher the temperature, the faster a liquid will evaporate and therefore the higher the pressure must be for the rate of condensation to equal the rate of evaporation. Raising the temperature of water, for example, by just ten degrees (Celsius) nearly doubles the vapor pressure. And, of course, if the water is in an open container, it will evaporate nearly twice as fast. |

|

This is the end of Lesson 2. Be sure that you complete and hand in the Problem Set and the Experiment for this lesson. Answers for the Self Quiz can be found on the Wrap Up page.