Lesson 2: Phase Changes

Changing the temperature of a material is not the only process that involves heat. In this section, we'll examine the process of changing phase; first we'll look at heating and cooling curves as a way to express the changes occuring with the addition (or removal) of heat from a material and then we'll do some calculations involving heat and phase changes.

Heating & Cooling Curves | Calculations Involving Phase Changes

Heating & Cooling Curves

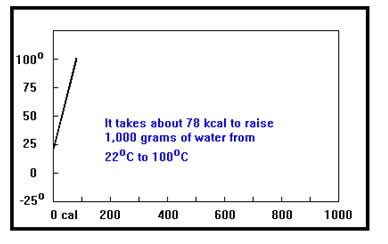

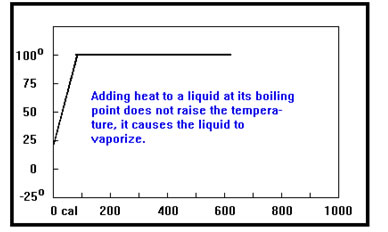

In the last section, we found that raising the temperature of 1,000 g of water from 22°C to 100°C requires 78,000 cal of heat. This process is shown in the graph on your screen. As we add heat the temperature slowly rises. What would happen to the temperature if, after reaching 100°C, we continue to add heat?

. |

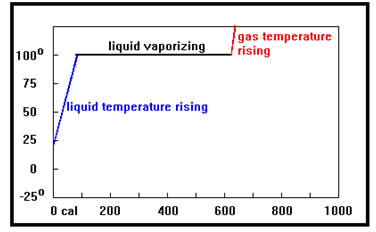

The graph is called a heating curve. It shows how the temperature changes as heat is added to a sample of material. The horizontal axis shows the amount of heat added, in the case in calories. Some heating curves show how the temperature changes with time as heat is added, so the horizontal axis shows time rather than the amount of heat. As long as heat is being added at a constant rate, the two kinds of heating curves are equivalent |

If you guessed that the temperature would no longer change, you’re right.

Once a liquid reaches its boiling point, any additional heat added causes liquid to change to gas but the temperature of the liquid remains at its boiling point. This is shown by the flat portion of the curve. The temperature at which the curve becomes flat is the boiling point. That does not change if the mass of the sample changes, but it does depend on what the liquid is. |

|

The length of the flat portion of the heating curve depends on the mass of the sample – more heat is required to vaporize a larger sample, so the length of the flat portion will be longer.

It also depends on the heat of vaporization. The heat of vaporization is the amount of heat required per gram to boil a liquid. A sample with a high heat of vaporization will require more calories per gram to boil, and thus the flat portion of the curve will be longer.

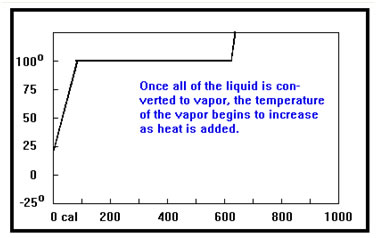

Once all of the liquid is converted to gas, adding more heat will cause the temperature of the gas to increase, and the curve resumes its upward climb. Notice that the temperature of the gas rises faster than the temperature of the liquid. This is because the specific heat of the gas is less than that of the liquid. It takes only 0.5 cal per gram to heat the gas by one degree, but 1.0 cal per gram – twice that of the gas – to heat the liquid by one degree. |

|

|

The slope of the curve as it climbs upward depends on the mass of the sample – it takes more heat to raise the temperature of a lager sample, so the curve will climb more slowly. It also depends on the specific heat of the sample. The specific heat measures the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one gram of material by one degree. The higher the specific heat, the more heat will be required to raise the temperature, and the more slowly the graph will climb. |

Since it takes more heat per gram to raise the temperature of the liquid, the curve rises more slowly when the sample is in the liquid phase than it does when the sample is in the gas phase.

Another way to say the same thing is that the slope of the liquid portion of the curve is less than the slope of the gas portion.

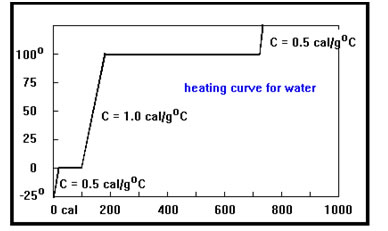

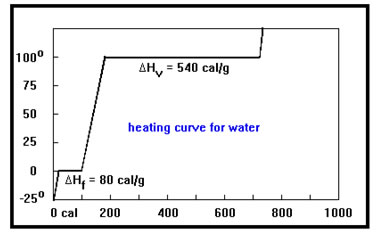

Here is a more complete heating curve for water with two flat portions, one at the melting point, where adding heat causes the solid to melt, and the other at the boiling point. The temperatures of the gas and the solid rise faster than the temperature of the liquid because of their specific heats are lower. |

|

Because the mass of the sample is the same though out the process of heating, differences in the slopes of the three portions of the curve that are rising are due entirely to the differences in the specific heats of the solid, the liquid, and the gas.

Study the curve for a moment and see if you can tell whether the specific heat of the gas is more or less than the solids…

The two slopes are actually identical. Both the solid and the gas have specific heats of close to 0.5 cal/g°C.

Notice also that the line for melting is shorter than the line for vaporizing – it takes less heat to melt the solid than it does to vaporize the liquid.

Again, since the mass of the sample does not change, the only difference between the two flat portions of the curve is that it takes more heat to vaporize a gram of liquid water at its boiling point than it does to melt a gram of solid ice at its melting point.

Like heat capacities, these two quantities are among the characteristics of a material that define its physical properties.

Exercise 8 in your workbook gives you some practice drawing heating curves like the ones we just looked at, and cooling curves. A cooling curve is just like a heating curve, except that the heat is being removed, so the temperature goes down.

In fact, a cooling curve will be the mirror image of the corresponding heating curve. The curve slopes down and to the right, with the slopes of the lines equal to be opposite in sign to those of the corresponding portions of the heating curve.

Where a heating curve slopes up sharply and to the right, the cooling curve slopes up sharply and to right, the cooling curve slopes down sharply and to the right.

The flat portions of the two curves are identical, but occur in reverse order, since as you heat a solid, it first forms a liquid (melts) then a gas (vaporizes), whereas cooling a gas forms first a liquid (the opposite of vaporizing) then a solid (the opposite of melting).

Answers to Exercise 8:

a. (The slopes of the lines are arbitrary. The y-axis is labeled in degrees Celsius; the x-axis could be labeled in either "time" or "heat added.")

b. (The slope of the first line should

be about half that of the second.The y-axis is labeled in degrees Celsius; the x-axis could be labeled in either "time" or "heat removed.")

Calculations Involving Phase Changes

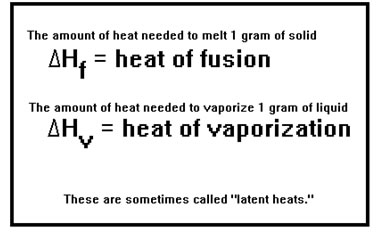

The heat required to melt one gram of solid is called the Heat of Fusion and is given the symbol ∆Hf. The heat required to vaporize a gram of liquid is called the Heat of Vaporization and has the symbol ∆Hv.

|

|

Since changing phase (solid to liquid or liquid to gas) involves no change in temperature, the units of heat of vaporization and the heat of fusion are calories per gram: cal/g.

Compare these units with those of the heat capacity: cal/g°C. Since heat capacity is a property associated with changing the temperature, units of temperature must be included.

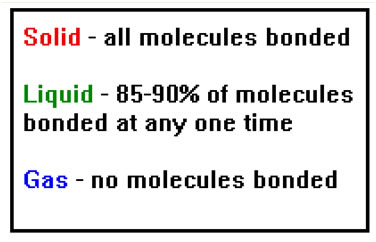

Heat of Fusion are typically much less than Heat of Vaporization because only 10-15% of the bonds in a solid must be broken at any one time for it to become a liquid, but all of the bonds must be broken for the liquid to change to a gas.

In a sense, a liquid is like a very fine powder made of particles with on the order of 10-20 molecules each. However, unlike a fine powder, the particles are constantly trading molecules as bonds break and reform throughout the liquid.

Another analogy is that a liquid is a gas whose molecules are held in close proximity by the external pressure – the pressure of the air. And in fact, the boiling point of a liquid and the melting point of a solid both depend on the external pressure. There are no liquids in a vacuum.

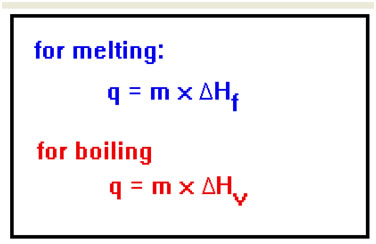

The total amount of heat required to melt a solid, once it has reached its melting point, is equal to its Heat of Fusion multiplied by the mass of material to be melted. Similarly, the amount of heat required to vaporize a liquid at its boiling point is its mass times its Heat of Vaporization. Note how the units work out: multiply a mass (g) by a heat of fusion (cal/g), and the answer is in units of heat: calories – the units of mass cancel. |

|

Heats of fusion and vaporization are also sometimes given in units of Joules per gram or even calories or Joules (or kilocalories or kilojoules) per mole.

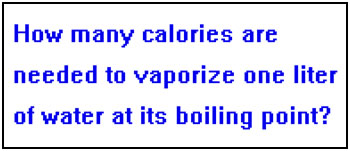

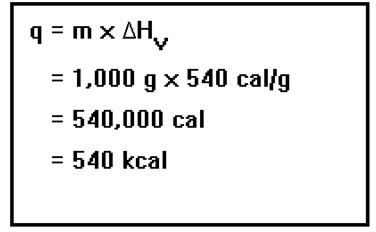

We found that 78,000 cal of heat were required to raise the temperature of a liter of water from room temperature to its boiling point. How let’s see how much heat would be require do vaporize that same liter of water once it’s at 100°C.

Recall from the heating curves that changing phase – in this case from liquid to gas – involves no change in temperature. Of course, the change can only occur at the boiling point, but it is not necessary to know what that temperature is.

We already determined that the mass of the water is 1,000 g. The heat of vaporization of water is 540 cal/g. Therefore, the heat needed is 1,000 g multiplied by 540 cal/g. This is equal to 540,000, or 540 kcal. |

|

Heats of vaporization can be looked up in a variety of sources. Most texts have short tables of these properties and much more extensive listing can be found in books such as CRC’s Handbook of Chemistry and Physics or Lange’s Handbook of Chemisty.

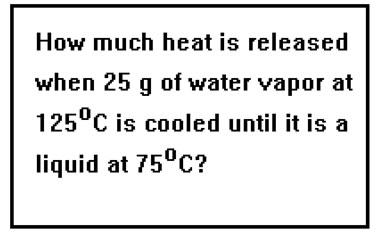

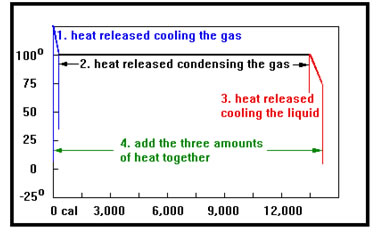

Some problems require you to use both the equations that apply to temperature changes and those that apply to phase changes. For example, let’s determine the amount of heat that would be released when 25 g of water vapor at 125°C until it is a liquid at 75°C.

In this problem we will need to know the boiling point of water: not to determine the heat released when it condenses, but to determine the heat released cooling it from 125°C to its boiling point. To know what change in temperature is involved, we need to know to what temperature the water is cooling.

We will also need to know the boiling point to determine the heat released when the water cools from its boiling point to 75°C.

We solve this problem in four steps. First we calculate the heat released when the gas cools from 125°C to the boiling point, 100°C. Then we determine the heat released when the 100° gas condenses to a liquid. Next, we find the heat released when the 100° water cools down to 75°C. Finally, we add the three heats together to find the total amount of heat released. |

|

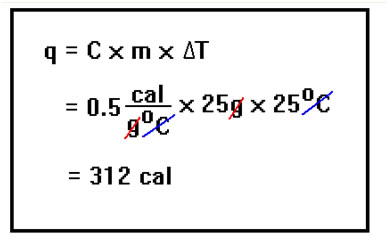

To do this we will need three additional pieces of information about water: the heat capacity of the gas, the heat of vaporization, and the heat capacity of the liquid.

The energy released when a substance is cooled is exactly the same as the energy needed to heat it that same number of degrees. The specific heat of water vapor is 0.5 cal/g°C, we are cooling the water by 25°, and its mass is 25 g. The amount of heat released is 312 cal. |

|

|

|

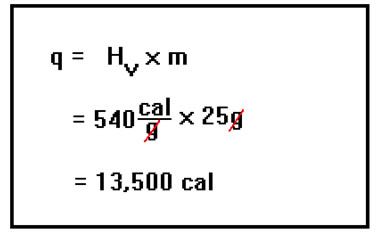

The energy released when a gas condenses to a liquid is exactly the same as the energy needed to vaporize the same mass of liquid to a gas. The heat of vaporization of water is 540 cal/g and we have 25 g of water vapor, so the energy released will be 540 times 25, or 13,500 cal. |

|

|

|

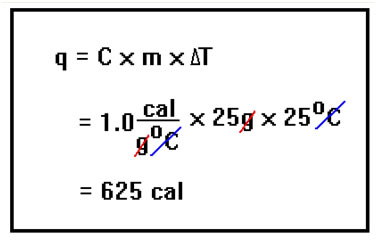

The specific heat of liquid water is 1.0 cal/g°C, so the heat released when the liquid cools the 25°C from 100°C down to 75°C is 625 cal. |

|

|

|

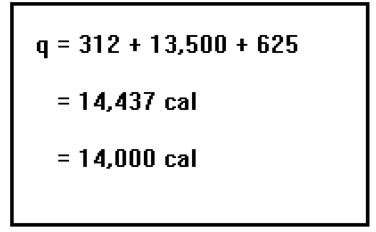

The total amount of heat release is just the sum of these three amounts, which, rounded to two significant digits, is 14,000 cal. |

|

Note that well over 90% of the heat released is released during the condensation of the gas it a liquid. This is the heat released as a result of forming the intermolecular hydrogen bonds between the water molecules – another demonstration of the unusual strength of hydrogen bonding.

Exercises 15 and 16 in your workbook contain some practice problems of this type. Be sure to try them before you continue with the last section of this lesson. You’ll find the answers below.

As you work these problems, be sure to think about whether the problem involves a temperature change, a phase change, or both – and use the appropriate equation or equations. You can find any heat capacities, heat of fusion or heat of vaporization you need in your text.

Answers to Exercise 15:

a. 80 cal/g

b. -80 cal/g

c. 9,600 cal

d. 2,800 cal

e. 600 g

Answers to Exercise 16:

a. 3,900 cal (2 sig. dig.; don't round the individual heats for each step, wait until the final result of 3925.77 cal and then round to 2 s.d.)

b. 240 g of water at 22 oC