Lesson 2: Heat Capacity

Energy is the ability to do work. Kinetic energy is energy an object has because it is moving. The amount of kinetic energy depends on the speed and the mass of the moving object.

More precisely, the kinetic energy of a moving object is equal to one half of its mass times its velocity squared. (KE = 1/2mv2.) Therefore doubling a moving object’s mass doubles its kinetic energy but doubling its velocity increases its kinetic energy by a factor of four.

Other kinds of energy that you may be familiar with include electrical energy – which is due to the motion of charged particles, usually electrons – and light energy – an electromagnetic wave that propagates through space at about 300 million meters per second.

In this section of the lesson, we'll examine one important form of energy, heat, and see how it relates to (but is not the same as) temperature. We'll also learn about a property of materials called heat capacity and do some calculations with heat capacity.

Heat vs. Temperature | Heat Capacity | Heat Capacity Calculations

Heat vs. Temperature

Heat is also a form of kinetic energy. A material feels hot because the atoms of molecules of which it is made are moving. The faster they move, the hotter the material feels.

There are three ways in which molecules can move. They can move from one place to another, motion that is called “translation.” This is what happens when you throw a ball or drop a heavy weight. Molecules can also turn over in place. This is called rotational motion. Finally, molecules can vibrate.

The molecules in a solid are held in place by bonds to neighboring molecules, so they cannot translate or rotate. The only motion they are capable of is vibrational motion. In a liquid, translation is severely hindered due to the close proximity of other molecules. Rotation is possible but it, too, is hindered, and most of the kinetic energy of a liquid is due to the vibrational motion of the molecules. Only in gases do translation and rotation make a significant contribution to the kinetic energy. Even so, a gas must be much hotter than the boiling point before the energies of translational and rotational motion begin to rival the energy of vibrational motion.

When the fast moving molecules of a hot material collide with the slow moving molecules of a cold material, they cause the slower moving molecules to speed up, while they, in turn, slow down. The cold material heats up, the hot material cools down, and we say that heat has been transferred.

The ability of materials to conduct and to transfer heat varies widely. Metals conduct and transfer heat very efficiently, so a cold piece of metal feels quite cold to the touch – the metal conducts heat away from your finger very rapidly. But an equally cold piece of wood doesn’t feel as cold as the metal because the wood doesn’t conduct heat away from your finger as rapidly.

Temperature measures the average heat energy of the molecules of a material. When a hot material contacts a cold material the temperature of the cold material rises and that of the hot material falls.

More precisely, the temperature measures the average kinetic energy of the molecules of a material, but this is what we familiarly call heat. If two gases are at the same temperature, their molecules will have the same average kinetic energy. This means that in the gas with the heavier molecules, those molecules must be moving more slowly than the molecules of the lighter gas.

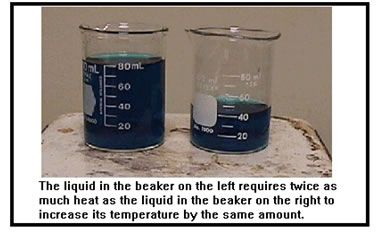

But temperature does not measure the total amount of heat energy a material contains. 2 kilograms of a material at 100°C has twice as much energy as 1 kilogram of the same material at 100°C because there are twice as many molecules with the same average kinetic energy.

Therefore, to relate the amount of heat energy required to cause a particular temperature change to the magnitude of that change, we will have to take into account the mass of the material being heated or cooled.

Heat Capacity

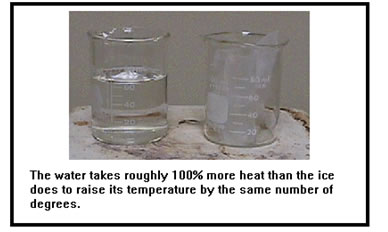

Similarly, different materials have different capacities for storing energy as heat. For example, it takes twice as much heat to raise the temperature of 1 gram of liquid water by 1°C as it does to raise the temperature of 1 gram of solid ice by 1°C.

The differences in the abilities of various materials to “store” energy as heat are related partly to the complexity of their molecules which determines the number of different ways they can vibrate.

A complex molecule has many different “modes” of vibration and it takes more heat to increase the energy of each of the many modes of vibration in a complex molecule that it does to increase the energy of each of a relatively few modes in a less complex molecule, all to the same average level of kinetic energy.

Another factor is the strength of the bonds involved. It takes more energy to get atoms bonded together strongly to vibrate than it does to get weakly bonded atoms to vibrate.

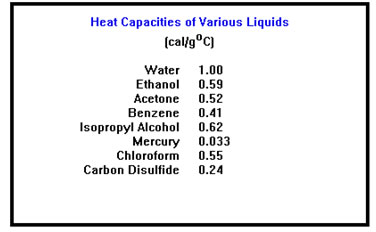

We describe this by saying that different materials have different heat capacities, that is, different capacities for storing heat. (Another, more precise, term that is used for heat capacity is specific heat.)

|

There is, unfortunately, not universal agreement on what the terms “heat capacity” and “specific heat” mean. However, for our purposes, you can assume that both refer to the number of calories of heat required to raise the temperature of one gram of a substance by one degree Celsius. |

One major point, however, is that the heat capacity and specific heat both measure the ability of a substance to store energy as heat. A material with a high heat capacity is one to which you must add a great deal of heat energy to cause a particular temperature change. A smaller amount of heat would be required to cause the same temperature change in an equal mass of a material with a smaller heat capacity.

Heat Capacity Calculations

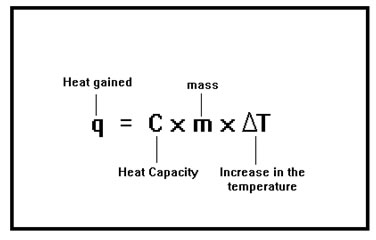

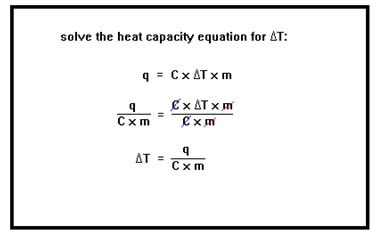

Mathematically, the amount of heat, q, required to raise the temperature of a material is equal to the heat capacity of the material times the mass times the change in temperature.

The other words, the amount of heat needed is the amount needed to change one gram by one degree, multiplied by the number of grams and multiplied again by the number of degrees. Examine the units of the heat capacity, cal/g°C to see that performing these multiplications gives you an answer in calories, units of heat. (Strictly speaking, the value of the heat capacity changes as the temperature changes, but the change is so small that, for our purposes, we can ignore it.) |

|

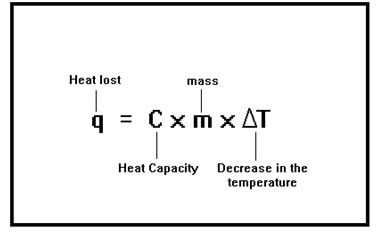

This equation also describes the amount of heat lost by a material when its temperature goes down. In this case, q and ∆T will be negative numbers because heat is lost and the temperature decreases. |

|

The triangle in front of T, the symbol for temperature, is a Greek letter: capital delta. It stands for “change in…” So the symbol “delta T” represents “change in temperature.”

The convention for computing the change in a quantity is to subtract its initial value from its final value, so that a decrease results in a negative number and an increase results in a positive number.

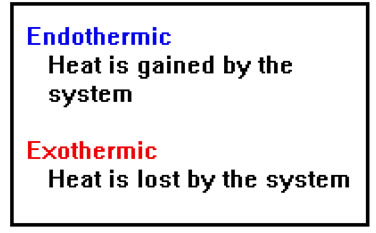

Any process in which the system – that is, the material we are interested in – loses heat is called an exothermic process. In an exothermic process, q is negative. Any process in which the system gains heat is called an endothermic process. In an endothermic process q is positive. |

|

We are free to choose whatever we want to be the “system.” In practice, we choose it from convenience. Since here we are considering temperature and phase changes, we choose the system to be the particular sample of material whose temperature and/or phase is changing.

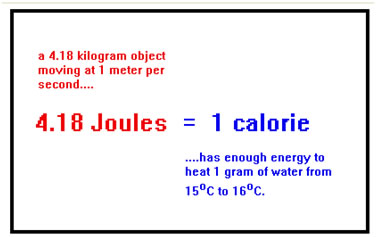

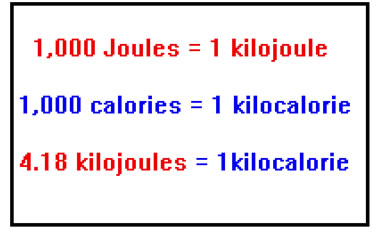

We measure heat energy in units of joules or calories.

A joule is the kinetic energy of a 1 kilogram object traveling at 1 meter per second. A calorie, which is about 4.18 joules, is defined as the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 gram of water from 15°C to 16°C. |

|

|

|

You might also see units of kilojoules (1,000 J) or kilocalories (1,000 cal). A kilocalorie is the amount of energy in a food Calorie (spelled with a capital “C”). |

|

|

|

In solving problems using the heat capacity equation, make sure that the units of mass and temperature that you use match the units of mass and temperature in the value of the heat capacity. Heat capacities are almost always given in calories per gram per degree Celsius, so the value of m you use must be in grams and the value of the temperature change should be in units of °C. However, since the size of a Kelvin is the same as the size a degree Celsius, the value of a change in temperature will be the same whether it’s in Kelvin or °C.

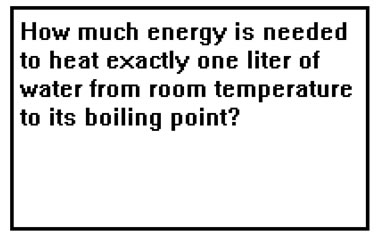

Let’s use the information we have so far to calculate the amount of heat it would take to raise one liter of water from room temperature (about 22°C) to its boiling point at 100°C, given that the specific heat of water is 1.0 cal/g°C. (This, by the way, is a number you should memorize.)

Here is one possible approach to the problem:

You know that you want an amount of heat related to an increase in temperature. This requires that you use the heat capacity equation.

Examining the equation, you find that you need three things:

- The heat capacity of the substance being heated (simple - it’s given in the problem);

- The temperature change (also simple, the problem states the initial and final temperatures)

- The mass of the sample (not-so-simple – the problem gives you a volume, one liter, not a mass).

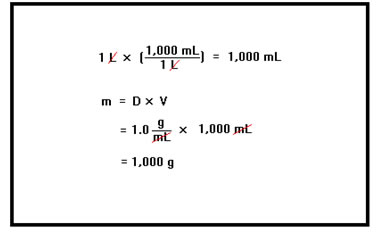

Do you remember how to calculate mass from volume? This is a density problem and the density of water is 1.0 g/mL. First, we need that mass of the water. One liter is 1,000 mL and the density of water is 1.0 g/mL, so that one liter of water has a mass of 1,000g. |

|

We assume that this problem is asking about exactly one liter of water, so we can solve it to an arbitrary degree of precision. We have chosen values of the heat capacity and density of water to two significant digits, so our answer should have two significant digits.

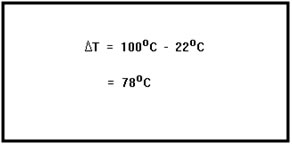

Raising the temperature from 22°C to 100°C is an increase of 78°C. So ∆T = 78°C. The temperature is increasing, so ∆T is a positive number. |

|

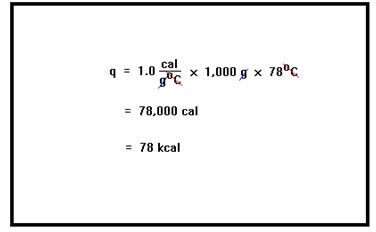

The amount of heat required in this endothermic process will be the specific heat of water, 1.0 cal/g°C, times the mass of the water, 1,000 g, times the change in temperature, 78°C. The answer is 78,000 cal or 78 kcal. |

|

Notice how the units of mass and temperature cancel to give the answer in units of heat, in this case calories because we used a value for the heat capacity in calories.

The answer also makes sense numerically. Recall that the food energy of two 60 Calorie (60 kcal) slices of bread would heat about 1.75 liters of water to boiling. 1 liter of water is a little over half of 1.75 liters and 78 kcal is a little over half of 120 kcal.

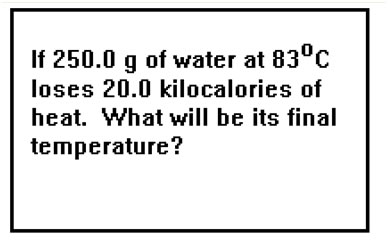

Here’s another sample problem. To what temperature would 250.0 g of water at 83°C fall if it lost 20,000 calories of heat?

This problem is very much like the one we just solved – easier, in fact, because the mass of the water is given directly.

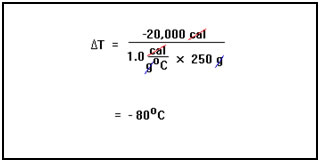

In this case, however, the process is exothermic because heat is being lost from the system, so the value of q is negative and the value for the temperature change we calculate should be negative.

Also, we are looking for the final temperature, not the temperature change. However, since we know the initial temperature, and the heat capacity equation will tell us the change in temperature, it’s a simple matter to determine the final temperature: simply add the (negative) temperature change to the initial temperature.

We are interested in the change of temperature, ∆T, which will be negative in this exothermic process. Therefore, we first solve our equation for ∆T. ∆T equals q divided by the mass times the specific heat of water. |

|

Since the heat is being lost, q is a negative number. We find that the change in temperature is -20,000 cal divided by 1.0 cal/g°C times 250 g. This equals -80°C. In other words, the temperature will fall by 80°C. |

|

Note again that the units cancel in such a way that the units of the answer are in °C, units of temperature. The answer also makes numeric sense. The magnitude of the fall in temperature is similar to that of the rise in temperature of the last problem, which we expect because both the amount of heat and the mass of water are smaller by about the same ratio – a factor of four or so. |

|

Since the temperature was originally 83°C, and it drops by 80°C, the final temperature of the water will be 3°C, just a few degrees above freezing. |

|

Most of the problems in this lesson have several steps in them. It’s a good idea when you’ve finished a problem to read it over quickly one more time to makes sure you’ve found what the problem asks for. In this problem, many students would stop once they had computed the change in temperature when the problem actually asks for the final temperature.

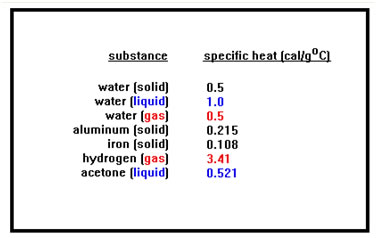

When doing problems of this type, be sure you use the right value for the specific heat. This value is different for each substance and it even changes when a substance changes from solid to liquid or from liquid to gas. You don't need to memorize any of these except for the specific heat of liquid water. |

|

When looking up values for heat capacities, pay particular attention to the units of the value you are given (is it in calories or joules?) and the phase of the substance in the table. As you will see, for some problems, you will have to use several different values of the heat capacity corresponding to different phases (solid, liquid, and/or gas) of the same substance.

Exercises 11 and 12 in your workbook provide you with some practice solving problems of the type we just finished. Work though these examples before you continue. You’ll find the answers below.

Exercise 11 answers:

a. 1.8 x 102 cal

b. 1.1 x 104 cal

c. 24.5 oC

d. 1,000 g

Exercise 12 answers:

a. 48 oC

b. 17 cal

c. 0.11 cal/goC

d. 0.058 cal/goC

e. 0.4 cal/goC