Lesson 6: Solutions of Acids & Bases

In this part of Lesson 6 we’ll study some of the concepts you’ll need to understand the technique of acid-base titration.

An acid-base titration is a technique in which precisely measured volumes of acid and base solutions are mixed until the two just neutralize each other. Then, from the measured volumes and the known concentration of one solution, the concentration of the other can be calculated. With simple equipment, the technique can be used to determine the concentration of an unknown acid or base solution to within a few tenths of a percent or less.

Multiprotism/Multibasism (Review) | Moles & Equivalents | Equivalent Weights | Molarity & Normality

Multiprotism/Multibasism (Review)

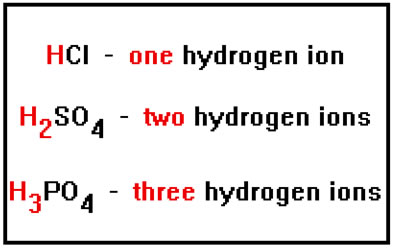

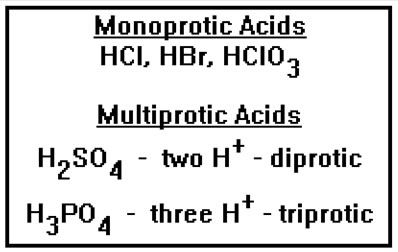

Let’s start with the concepts of multiprotism and multibasism. Recall that some of the acids we named had only one positive hydrogen ion, while others had two or three. Hydrochloric acid, for example, has only one hydrogen ion, while sulfuric acid has two and phosphoric acid has three.

|

The reason, of course, is that the chloride ion has a charge of 1-, and so requires only one H+ ion to balance its charge. The sulfate ion, on the other hand, has a charge of 2- and so requires two hydrogen ions to balance its charge. The phosphate ion has a charge of 3- and requires three H+ ions. |

|

Acids that have more than one hydrogen ion are called multiprotic. Sulfuric acid, with two, is diprotic while phosphoric acid, with three, is triprotic. Another term that is often used for multiprotic acids is “polyprotic” acids. The two terms mean the same thing. |

|

Similarly, a base that has more than one hydroxide, for example, would be dibasic and aluminum hydroxide would be tribasic. Again, the term “polybasic” is sometimes used instead of multibasic. Ammonia is a monobasic base, even though it has no hydroxide ions, because it can react with an acid and accept one proton. There are also multibasic bases that have no hydroxide ions. They are multibasic because they react with acids and accept two or more hydrogen ions. |

Moles & Equivalents

We're quite familiar with the concept of moles in chemistry at this point. However, when dealing with acids and bases, we sometimes find that using moles when working with acids and bases is not the most useful concept. Instead, we use a related concept, the concept of equivalents.

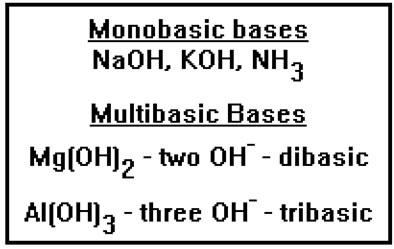

An equivalent is defined as the amount of an acid that contains one mole of H+ ions or the amount of a base that contains one mole of OH- ions.

|

Since bases are also defined as proton acceptors, one equivalent of a base can also be defined as the amount of base that can accept one mole of H+ ions. The two definitions are equivalent, since one mole of OH- ions can accept one mole of H+ ions. |

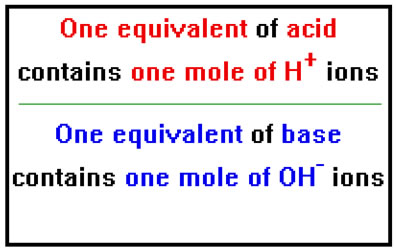

Since a monoprotic acid has only one hydrogen ion per molecule, one mole of a monoprotic acid is the same as one equivalent. The same is true of a monobasic base. Since it has only one hydroxide ion per “molecule” (or, can accept only one proton per molecule) one mole and one equivalent are the same thing. |

|

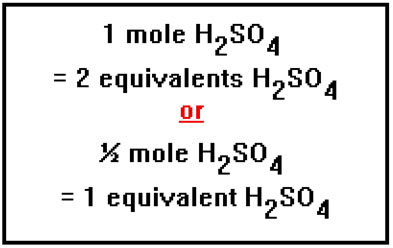

A diprotic acid has two hydrogen ions per molecule, so that one mole of a diprotic acid is the same as two equivalents. That is, a diprotic acid has two equivalents per mole. Similarly, a dibasic base has two equivalents per mole, or one half of a mole per equivalent. |

|

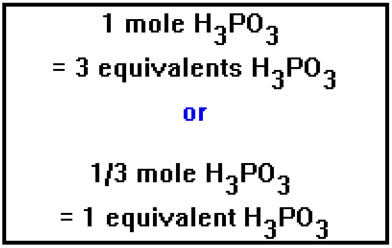

A triprotic acid has three hydrogen ions per molecule, so that one mole of a triprotic acid is the same as three equivalents. In other words, a triprotic acid has three equivalents per mole. And the same statement can be made for tribasic bases. One mole contains three equivalents, or one equivalent is the same as one third of a mole. |

|

It’s important that you be able to look at the formula of an acid or base and know immediately the number of equivalents per mole. For any acid whose formula begins with H or for any base whose formula ends with OH, the number of equivalents per mole is the same as the number of H’s in the acid or OH’s in the base.

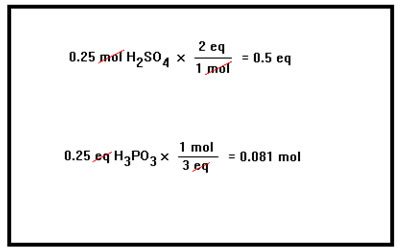

To convert from moles to equivalents, simply multiply the number of moles by the number of equivalents to moles. To convert from equivalents to moles, divide the number of equivalents by the number of equivalents per mole. |

|

This is the same conversion factor method we use to convert from one set of units to another, or to convert from grams to moles, moles to molecules, grams to molecules, etc. It works here, of course, because for a given acid or base, the number of moles and the number of equivalents are directly proportional. |

|

Exercise 7 in your workbook has some sample conversions of this type. You’ll find the answers below. As always, if you work enough of this type of problem that it becomes automatic – even boring – you’ll never have to study hard to remember how to do them again.

Answers to Exercise 7:

7. c. How many equivalents are there in each of the following?

2 moles HCl = 2 eq

0.4 mole HCl = 0.4 eq

0.4 mole H2SO4 = 0.8 eq

1.2 mole H3PO4 = 3.6 eq

0.7 mole NaOH = 0.7 eq

4.3 mole Mg(OH)2 = 8.6

eq

d. How many moles are there in each of the following?

3.2 eq HCl = 3.2 mole

0.76 eq H2SO4 = 0.38 mole

0.76 eq H3PO4 = 0.25 mole

1.56 eq Mg(OH)2 = 0.78

mole

1.56 g H2SO4 = 0.0159 mole (Did you notice that this is just a grams-to-moles conversion?)

Equivalent Weights

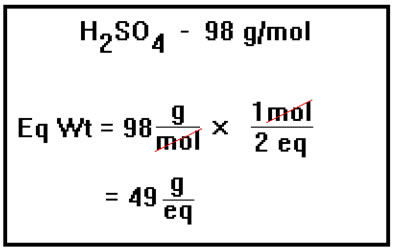

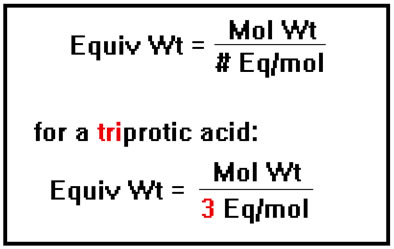

The molecular weight of a compound is the weight (in grams) of one mole. The equivalent weight of an acid or a base is the mass (in grams) that contains one equivalent.

Monoprotic acids have one equivalent per mole, so the weight of one equivalent is the same as the weight of one mole. The same is true of monobasic bases. For other acids and bases, since there is always an integral number (2, 3, etc.) of equivalents per mole, the equivalent weight will always be an integral fraction (1/2, 1/3, etc.) of the molecular weight.

Suppose, for example, you wanted to know the equivalent weight of H2SO4. Since one mole contains two equivalents, the molecular weight must be the weight of two equivalents. The equivalent weight is therefore just one half the molecular weight. If you pay attention to the units, as usual they will guide you to divide the molecular weight by the number of equivalents per mole. |

|

To check your answer, keep in mind that for any acid or base, the equivalent weight can never be more than the molecular weight. It must always be either equal to or some integral fraction of the molecular weight, depending on whether the acid or base has one or more hydrogen or hydroxide ions. |

|

For a triprotic acid or a tribasic base, the equivalent weight would be one third the molecular weight. |

|

Note how the units cancel to give you an equivalent weight in units of “grams per equivalent.” It also helps to remember that the number of equivalents per mole is just the number of acidic hydrogens per molecules of an acid, or the number of hydroxide ions in the formula of a base. (Ammonia has one equivalent per mole.) For an acid, the acidic hydrogens are those that occur at the beginning of the formula. Acetic acid, HC2H3O2, for example, has only one. |

|

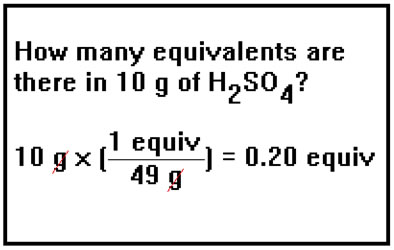

To determine the number of equivalents in a given mass of an acid or base, you would use the equivalent weight in the same way you used the molecular weight to determine the number of moles in a given mass of a compound. |

|

Another way to do the same thing is to determine the number of moles: |

|

Then multiply this number by the number of equivalents per mole: |

|

The end result is the same.

Here’s a problem for you to try.

How many equivalents are there in 1.50 g of Mg(OH)2?

(Here’s a hint: You must first determine both the molecular weight of Mg(OH)2 and the number of equivalents of base there are in one mole of Mg(OH)2.

Answer: 0.0514 eq

Now try Exercise 8 and check your answers below.

Answers to Exercise 8:

8. b. calculate the equivalent weights for these chemicals:

HCl 36.5 g/eq

H2SO4

49.1 g/eq

H3PO4

32.7 g/eq

NaOH 40.0 g/eq

Mg(OH)2 29.2 g/eq

c. What are the equivalent weights of these chemicals?

HNO3 = 63.0 g/eq H2S = 17.1 g/eq Ca(OH)2 = 37.1 g/eq

d. 45.1 g/eq

Molarity & Normality

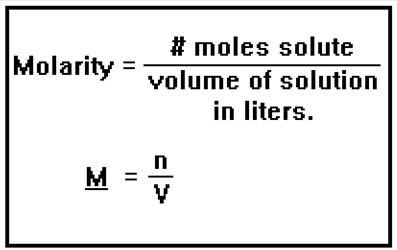

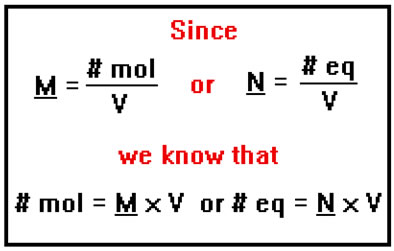

Recall that molarity is a way of expressing concentration. It’s defined as the number of moles of solute there are per liter of solution.

You can review the concept of molarity in Lesson 5. It is important to remember in using molarity that the number of moles is of the solute only, but the volume is of the solution, including both the solute and the solvent, and must be in liters.

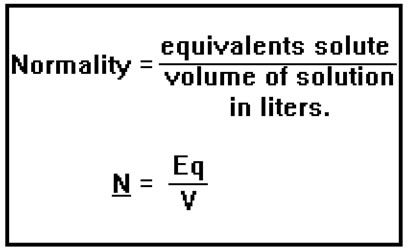

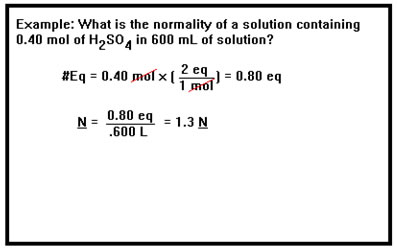

Normality is defined in exactly the same way except that instead of using the number of moles, you use the number of equivalents. Normality is the number of equivalents of solute per liter of solution.

Because the number of equivalents is the same as the number of moles of H+ ions in an acid or the number of moles of OH- ions in a base, normality is essentially just the molarity of the H+ or OH- ions, depending on whether we’re dealing with an acid or a base. You can see that normality is a convenient way to express the “acid strength” or an acidic solution or the “base strength” of a basic solution. (This is not the same as expressing whether the acid is a "strong acid" compared to a "weak acid" or whether the base is a "strong base" or a "weak base." We'll talk more about those terms in the next section of the lesson.)

One way to determine the normality of a solution is to calculate the number of equivalents of acid or base it contains and then divide that number by the volume of the solution in liters.

|

This says that a 0.40 M solution of H2SO4 has a concentration of 0.80 moles of H+ ions per liter of solution. This is twice the "acid strength" of a 0.40 M solution of HCl, which would have only 0.40 moles of H+ ions per liter. Thus, the advantage of expressing the concentrations of acids and bases in terms of normality is that the two solutions of equal normality have equivalent acid or base "strengths." This will be quite useful when we have to mix an acid solution with a base solution. |

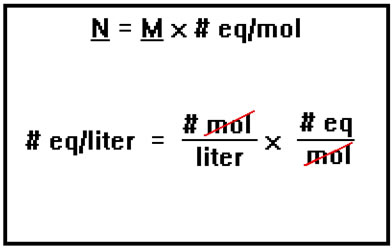

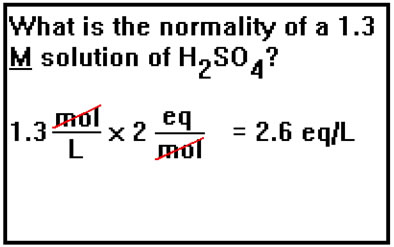

Another way to determine the normality of a solution is to first determine its molarity, then multiply this by the number of equivalents per mole of the acid or base that is the solute. Again, note that units “mol” cancel. If you always remember to include the unit when doing this sort of calculation, you will be unlikely to accidentally divide when you should multiply, or vice versa. Dimensional analysis helps keep things straight. |

|

|

|

Of course, the normality of a solution of a monoprotic acid or a monobasic base is the same as its molarity because the solute contains only one equivalent per mole.

Exercise 10 in your workbook contains some problems of this type for you to try. Be sure to practice before you continue. You can check the answers below.

Answers to Exercise 10:

10. a. 0.17 M or 0.33 N

b. 0.83 M or 0.83 N

c. 0.19 M or 0.39 N

d. 0.60 N

Dilution problems involve the change in the concentration of a solution that results when additional solvent is added – in other words, when a solution is diluted. We worked this kind of problem in Lesson 4 when we first learned about molarity.

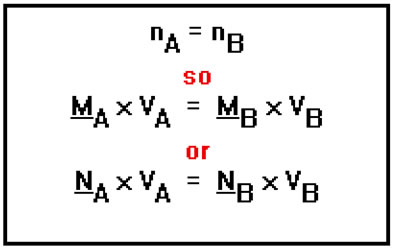

Obviously, since we are diluting, the new concentration must be less than the original. This also follows from the definition of concentration. The original solution and the diluted solution must contain the same number of moles (or equivalents) of solute, but the diluted solution has greater volume. Dividing by a greater volume results in a lower concentration.

The best way to deal with dilution problems is to make use of the fact that both the original and the diluted solutions must have the same number of moles (or equivalents) of solute.

|

We want expressions for the number of moles (or equivalents) in both the original, undiluted solution and the diluted solution, so we solve the concentration equation for the number of moles (or equivalents) of solute. |

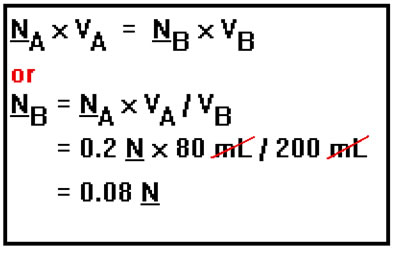

Since the number of moles (or equivalents) in the original solution (solution A) is the same as the number of moles (or equivalents) in the diluted solution (solution B), we can write the equation shown. We can now solve either of the last two equations for the concentration of the diluted solution, solution B. |

|

The choice of whether to use molarity or normality is determined by what you know the concentration of the original solution to be. If you know its molarity, you calculate the molarity of the diluted solution. If you know its normality, you will calculate the normality of the diluted solution. |

|

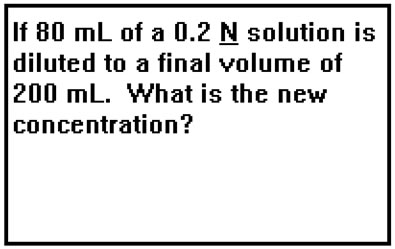

Suppose, for example, that 80 mL of a 0.2 N solution is diluted to a final volume of 200 mL. What is the new concentration?

|

In this problem, you are given the concentration and volume of the original solution (NA and VA) and the volume of the diluted solution (VB), and asked for the concentration of the diluted solution (NB). However, you could be given any three of those four quantities and asked for the fourth. For example, you might be told that 250 mL of a solution is diluted to 350 mL and the concentration of the diluted solution is found to be 0.35 M and then asked to compute the concentration of the original solution. Or perhaps you might be asked to what final volume should be 300 mL of a 0.75 M solution be diluted to get a solution whose concentration is 0.45 M. |

Simply use the equation involving normality and solve it for the concentration of the diluted solution. Then plug in the values of the three known quantities and compute the concentration you are looking for. |

|

Example 11 in your workbook contains this and two other examples of dilution problems. In the two other examples, you are asked in one for the volume of the new solution and in the other the volume of the original solution. In both cases, you use the same equation that we used here, but you will solve it for a different variable. Make sure you understand these two examples as well before continuing.

Here’s a problem for you to try.

45.57 mL of a solution is diluted to 63.40 mL. The diluted solution is found to have a concentration of 0.433 N. What was the concentration of the original solution?

Again, use the same equation as for all dilution problems, but this time you must solve it for NA.

Answer: 0.602 N

You may have noticed that we did not bother to convert from mL to L in these example problems. Had we done so, our answers would have been the same (except that in the problems in Example 11c our answers would have been in liters). We can use mL in these problems because we are dealing with ratios of volumes, and the volume ratios are the same whether we use liters or mL.

This is the end of this part of Lesson 6. Before going on to the last two parts, you may want to work on problems 1 through 3 in the problem set.

In the last parts of this lesson, we deal with titrations, a procedure in which solutions of an acid and a base are mixed together until they just neutralize one another. It is in this procedure that the concepts of equivalents and normality are most useful, since, as we will see, an acid and a base just neutralize one another when the number of equivalents (not the number of moles) of the two are exactly the same.