Lesson 6: Nomenclature of Acids, Bases, & Salts

We’ll begin this lesson by learning how to name bases, acids, and their salts.

Naming Bases

The easiest are the bases, since most of these are metal hydroxides, compounds you already know how to name.

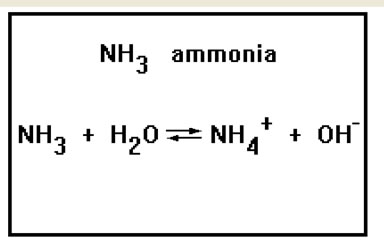

One common exception is ammonia, a base that is not a metal hydroxide. It has the formula NH3 and is the simplest member of a family of bases called the amines. The conjugate acid of ammonia is the ammonium ion, NH4+.

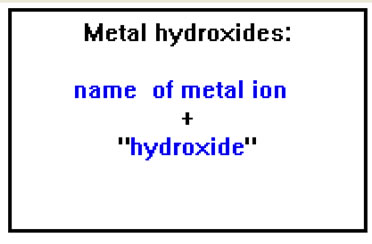

Metal hydroxides are named in the same way any other ionic compound is named. First give the name of the metal ion. Follow this with the name of the anion, which, in the case of bases, is “hydroxide”.

Metal hydroxides consist of a single positive metal ion and a number of hydroxide ions equal to the positive charge on the metal ion. Since each hydroxide ion has a charge of 1-, it will take one hydroxide ion to balance a 1+ metal ion, two hydroxide ions to balance a 2+ metal ion, and so forth.

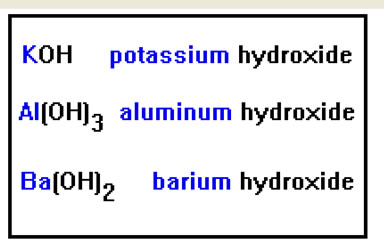

Here are some examples involving representative metals. Because each of these metals has only one possible oxidation state, which is equal to its group number in the periodic table, we don’t have to specify the metals positive charge in the name. |

|

These are the metals in groups IA, IIA and IIIA. You may also recall that silver and zinc have only one positive oxidation state, even though they are transition metals. Silver forms a 1+ ion and zinc a 2+ ion. Several other transition metals also form only one positive ion, but these are the only two we will encounter.

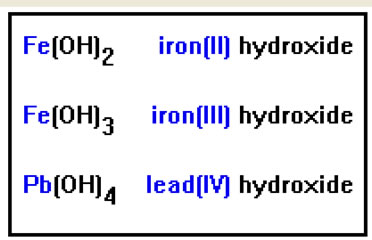

The next examples involve transition metals. These elements can have more than one positive ion, so the name must indicate which one it is. You can determine the positive charge by seeing how many hydroxide ions, each with a charge of minus one, it takes to make a neutral compound.

|

|

Be careful to note that the Roman numeral in parentheses following the metal ion does not, strictly speaking, refer to the number of hydroxide ions. It refers to the positive charge on the metal. For metal hydroxides, these two numbers are the same, but the distinction becomes important when the metal is combined with an anion that has a negative charge greater than one. FeO, for example, is iron(II) oxide because the iron atom has a charge of 2+.

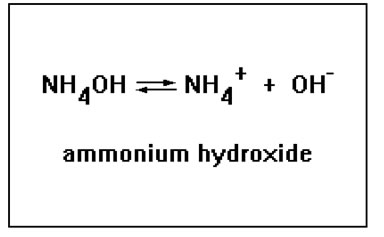

Another hydroxide compound that is basic is ammonium hydroxide. The ammonium ion, NH4+ is the conjugate acid of ammonia, NH3. But the ammonium ion is a very weak acid, while the hydroxide ion is a very strong base, so a solution of ammonium hydroxide is basic. |

|

Ammonium hydroxide is not as strong a base as sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide. This is not, however, because the ammonium ion acts as a acid and neutralizes the base, it is because the positive ammonium ion tends to associate with the hydroxide ion to form an ion pair, NH4OH(aq) which is neither an acid nor a base, thus reducing the concentration of free hydroxide ions in the solution. We'll discuss strengths of acids and bases a bit later in this lesson and then delve further into the topic in the third (and final) lesson about acids and bases.

Ammonia itself, NH3, is also a base. This molecule forms hydroxide ions when it dissolves in water by reacting with the water molecules. In fact, solutions of ammonia in water and solutions of ammonium hydroxide in water are indistinguishable. Ammonia and ammonium hydroxide do, however, behave quite differently under other circumstances, as, for example, in their pure forms (ammonia is a gas and ammonium hydroxide is a solid) or when they are dissolved in solvents other than water. |

|

Naming Acids

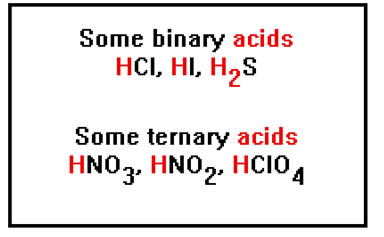

Acids are named in one of two ways, depending on whether they are binary acids – that is, they consist of only two elements – ore they are ternary acids, made up of three elements.

|

Note that “binary” does not mean “only two atoms.” Binary acids can have more than two atoms, but they are atoms of only two different elements. Similarly, ternary acids can have more than three atoms, but they are atoms of only three different elements. Many ternary acids are also called “oxy-acids” because one of the three elements is oxygen. |

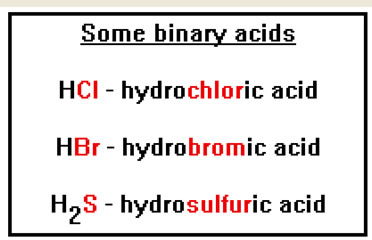

The names of the binary acids begin with the prefix “hydro,” followed by a root that is based on the name of the element the hydrogen is combined with, then the suffix “ic.” They end with the word “acid.” HCl, for example, would be hydrochloric acid. |

|

Only the binary acids that involve the halogens (F, Cl, Br, and I) are commonly used as acids. These are hydrofluoric, hydrochloric, hydrobromic, and hydroiodic acids. H2S is only weakly acidic in water, and so is usually referred to as hydrogen sulfide, while H2O is not really an acid at all (though it can function as one when it reacts with a strong base), it’s just plain water. H3N is actually a base not an acid. For this reason it is written instead as NH3, which you should recognize as the formula of ammonia. |

|

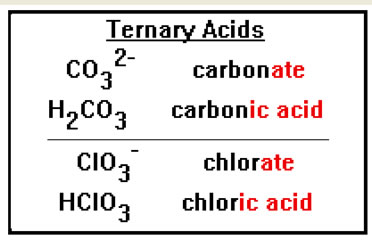

Ternary acids consist of a polyatomic ion combined with hydrogen. Their names of the polyatomic ions they contain. In general, the “ate” ending of the polyatomic ion is replaced with the “ic” ending and the word “acid” is added. To name these acids, you must remember the name, the formula, and the charge of each of the common polyatomic oxy-ions you learned in Chemistry 104. They are acetate, carbonate, nitrate, phosphate, sulfate, and chlorate. The two additional polyatomic ions you studied were the ammonium ion and the hydroxide ion. |

|

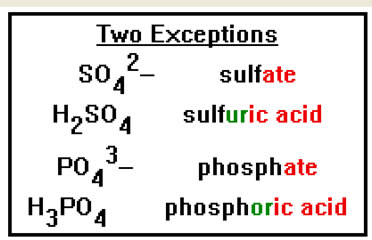

There are two exceptions to this general rule. The acid formed from the sulfate ion is called sulfuric acid, while the acid formed from the phosphate ion is called phosphoric acid. Note the addition of “ur” in the first name and “or” in the second. |

|

Note also that in all of these ternary acid (oxy-acid) names, the prefix “hydro” is NOT used. Including the “hydro” prefix in the names of the ternary acids and leaving if off of the names of binary acids are common errors among beginning students of chemistry. The “hydro” prefix is used only with binary acids, never with ternary acids. |

|

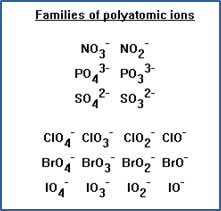

Most non-metal atoms that form polyatomic ions form more than one polyatomic ion. These ‘families’ of polyatomic ions all have the same charge, but different number of oxygen atoms. Nitrogen, sulfur and phosphorus each form two such polyatomic ions, while chlorine, bromine and iodine each form four. |

|

|

|

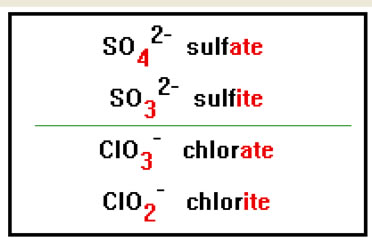

To name a polyatomic ion with one oxygen atom fewer than an “ate” ion, change the “ate” ending to “ite.” For example, to name the SO32- ion, which has one oxygen atom less than the sulfate ion, change the “ate” ending in sulfate to “ite.” The name becomes sulfite. |

|

||||||||

Each of these ions has one oxygen atom fewer then the corresponding “ate” ion, but the same negative charge. |

The other “ite” ions would therefore be:

|

||||||||

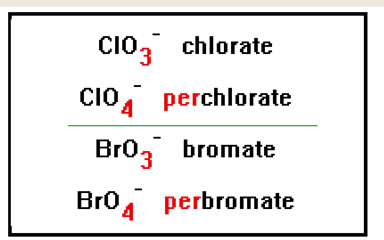

To name a polyatomic ion with one oxygen atom more than an “ate” ion, add the prefix “per” to the name. For example, the ClO4- ion has one more oxygen atom than the chlorate ion, and so would be called perchlorate. |

|

||||||||

The “per” prefix comes from the Latin and means “thoroughly,” “utterly,” or “very.” It occurs in words like perfect, pervert, pervade and is similar to the prefix “hyper,” as in hyperactive.

|

The other “per” ion would therefore be:

|

||||||||

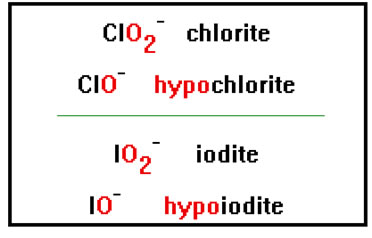

Finally, to name a polyatomic ion with one oxygen less than an “ite” ion, add the prefix “hypo” to the name. ClO- has one oxygen less than the chlorite ion, and so is called hypochlorite. |

|

||||||||

The “hypo” prefix also comes from Latin and means “beneath.” You probably recognize it from the word “hypo-dermic,” as in “hypodermic needle,” a needle used to deliver beneath the skin. |

The other "hypo" ion would therefore be:

|

||||||||

The complete series of ions based on chlorine would be: |

|

||||||||

|

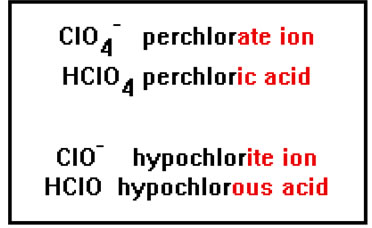

The acids that form from all of these polyatomic ions are named simply by changing the “ate” ending to “ic” or the “ite” ending to “ous” and adding the work “acid.” HClO4, the acid made from the perchlorate ion, is perchloric acid. HClO, the acid made from the hypochlorite ion, is hypochlorous acid. |

|

As before, in the case of sulfur and phosphorus, we add a “ur” or an “or” so that the sulfite ion forms sulfurous acid and the phosphite ion forms phosphorous acid. |

|

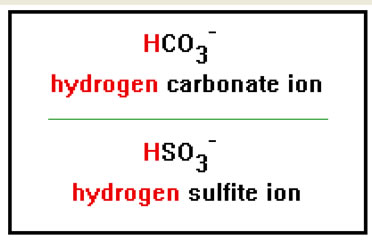

Polyatomic ions that have a negative charge greater than one can, under the right circumstances, associate with only one positive hydrogen ion. Carbonate, for example, can associate with a single hydrogen ion to form a new polyatomic ion with the formula HCO3-. This ion is called the hydrogen carbonate ion. |

|

|

Note that the charge on these ions is one less than the charge on the corresponding ions without the hydrogen. This is due to the 1+ charge on the hydrogen ion. Another common name for these ions is formed by adding the prefix “bi” to the original name:

|

Try your hand at Exercises 1 and 2 in the workbook now. Then check your answers before moving on.

Answers to Workbook Exercises 1 & 2:

1. |

a. |

NaOH |

sodium hydroxide |

Mg(OH)2 |

magnesium hydroxide |

||

Fe(OH)3 |

iron(III) hydroxide or ferric hydroxide |

||

b. |

NH3 |

ammonia |

|

NH4OH |

ammonium hydroxide |

||

c. |

HCl |

hydrochloric acid |

|

HI |

hydroiodic acid |

||

H2S |

hydrosulfuric acid (dihydrogen sulfide) |

2. |

b. |

PO33- |

phosphite |

H3PO3 |

phosphorous acid |

SO32- |

sulfite |

H2SO3 |

sulfurous acid |

||

c. |

HClO4 |

perchloric acid |

|||

HClO3 |

chloric acid |

||||

HClO2 |

chlorous acid |

||||

HClO |

hypochlorous acid |

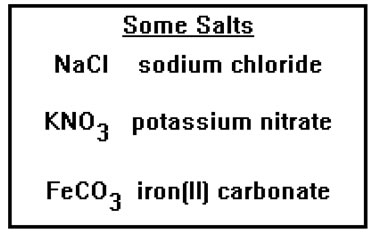

Naming Salts

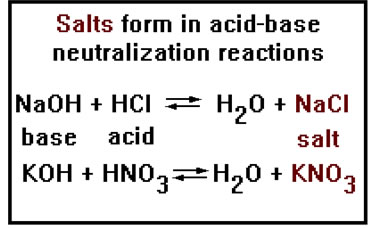

The last topic in this section on nomenclature is naming salts. These are ionic compounds formed between a positive ion from a base and a negative ion from an acid. They form when the acid and base react and neutralize each other.

|

As we saw in the last lesson, the other product from an acid-base neutralization is usually water. All salts are ionic compounds, but not all ionic compounds are salts. Salts are those ionic compounds that can be formed from an acid-base neutralization reaction. |

Salts are named simply by giving the names of the positive and negative ions. This is the same way we named the metal hydroxide bases to begin this lesson, except that now the negative ion is not hydroxide. Also remember, for transition metals, to include the Roman numeral that indicates the charge on the metal. |

|

You might also remember the Latin system for naming some of these compounds. FeCO3, for example, is also called ferrous carbonate. If you wish, you can review that system of nomenclature in Lesson 7 of Chemistry 104.

Exercises 3 and 4 in your workbook give you some practice figuring out formulas from names and names from formulas for acid, bases and salts. You should practice these until you’re familiar with them. You’ll find the answers below.

If you need further help, you’ll find a flow chart for naming acids, bases, and salts in Example 5 of your workbook. This chart summarizes all of the rules for naming that we’ve covered.

Answers to Workbook Exercises 3 - 4:

3. |

potassium hydroxide |

KOH |

potassium nitrate |

KNO3 |

calcium hydroxide |

Ca(OH)2 |

sodium nitrite |

NaNO2 |

|

ammonia |

NH3 |

sodium hypochlorite |

NaClO |

|

hydrobromic acid |

HBr |

sodium bisulfate |

NaHSO4 |

|

bromic acid |

HBrO3 |

sodium hydrogen carbonate |

NaHCO3 |

|

sulfuric acid |

H2SO4 |

sodium bicarbonate |

NaHCO3 |

|

sulfurous acid |

H2SO3 |

bicarbonate of soda |

NaHCO3 |

|

phosphoric acid |

H3PO4 |

magnesium perchlorate |

Mg(ClO4)2 |

|

periodic acid |

HIO4 |

aluminum sulfite |

Al2(SO3)3 |

4. |

NaOH |

sodium hydroxide |

Li2CO3 |

lithium carbonate |

Mg(OH)2 |

magnesium hydroxide |

Al(HCO3)3 |

aluminum bicarbonate |

|

NH4+ |

ammonium ion |

NH4Cl |

ammonium chloride |

|

OH- |

hydroxide ion |

NaKSO4 |

sodium potassium sulfate |

|

NO3- |

nitrate ion |

KBr |

potassium bromide |

|

NO2- |

nitrite ion |

HC2H3O2 |

acetic acid |

|

HI |

hydroiodic acid |

NaC2H3O2 |

sodium acetate |

|

HIO2 |

iodous acid |

HCl |

hydrochloric acid |

|

HIO4 |

periodic acid |

HNO2 |

nitrous acid |