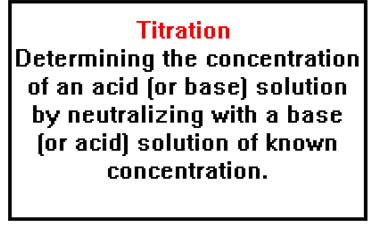

Lesson 6: Acid-Base Titrations

Titration is a technique in which precisely measured volumes of an acid solution and a base solution are mixed until they just neutralize one another. From the measured volumes of the two solutions and the concentration of one of them, you can calculate the concentration of the other.

In this section, we'll examine neutralization equations in more detail and spend some time discussing the lab work for this week.

Neutralization Equations | Lab Work

Neutralization Equations

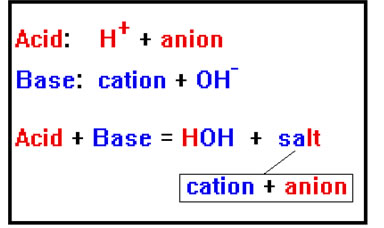

When a typical acid reacts with a typical base, the products are easy to predict. The H+ ions from the acid combine with the OH- ions from the base to form water, and the anion from the acid combines with the cation from the base to form a salt.

|

In the case of ammonia, which has no OH- ion, the H+ ion from the acid combines with ammonia itself, NH3, to form the NH4+ ion (the ammonium ion). This cation can then combine with the anion from the acid to form an ammonium salt. For example:

|

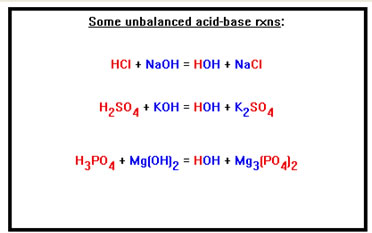

Here are some typical reactions between acids and bases. |

|

The formulas of the salts are determined by the charges on the two ions they are formed from. |

One Na+ combines with one Cl- to form NaCl Two K+ ions are required to balance the charge on one SO42- ion, so the formula of the salt is K2SO4 Three Mg2+ ions balance the charge on two PO43- ions, so the formula of the salt Mg3(PO4)2 In each case, the total number of positive charges must equal the total number of negative charges. |

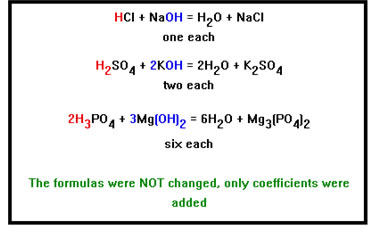

These reactions are called neutralization reactions. The acid and the base neutralize each other. To balance them, make the number of H+ ions from the acid the same as the number of OH- ions from the base by placing coefficients in front of the formulas. |

|

Exercise 12 in your workbook provides you with some practice completing and balancing acid-base neutralization reactions. Pause here and try these sample problems before going on. |

|

As you work through these problems, the keys are to focus on the number of H+ and OH- ions – making sure that you end up with the same number of each – and on the charges on the anion and cation to make sure you get the formula of the salt correct. In fact, if you find it impossible to balance one of these equations, it is probably because the formula of the salt is incorrect or you forgot to balance the number of H+ and OH- ions.

Answers to Exercise 12:

12. a. coefficients, in order

1:2:2:1

1:2:2:1

2:1:2:1

b. HCl + KOH ![]() KCl + H2O

KCl + H2O

2HNO3 + Ba(OH)2 ![]() Ba(NO3)2 +

2H2O

Ba(NO3)2 +

2H2O

H3PO4 + 3NaOH ![]() Na3PO4 + 3H2O

Na3PO4 + 3H2O

2H3PO4 + 3Ba(OH)2 ![]() Ba3(PO4)2 + 6H2O

Ba3(PO4)2 + 6H2O

If you had difficulty completing these, get help from an instructor.

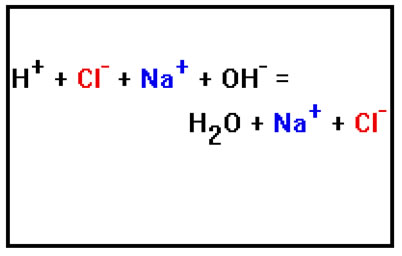

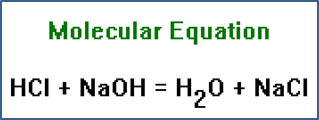

The chemical equations we have written so far are called molecular equations because they show the complete formulas of the reactants and products. We can also write ionic equations (showing how the chemicals dissociate - or don't dissociate - in solution) and net ionic equations (leaving out the spectator ions).

|

The term “molecular equation” is not entirely accurate. NaOH and NaCl do not exist as molecules. These are network solids in which no true molecules exist. The term persists because no better alternative has been found. |

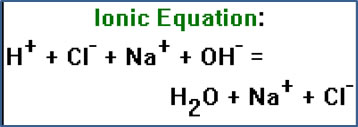

Ionic equations show the reactants and products which dissociate as ions. Ionic equations reflect the fact that when strong acids and bases and soluble salts are dissolved in water, they dissociate into separate positive and negative ions. |

|

|

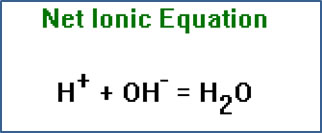

Another form of this equation, called the net ionic equation, shows only the species in the reaction which change in the course of the reaction. The net ionic equation is not as useful as an ionic or molecular equation, since it does not show what acid or base are involved. In fact, as you may notice, this is the net ionic equation for any strong protic (H+-containing) acid reacting with any metal hydroxide base. |

Strong Acids/Bases vs. Weak Acids/Bases

I referred to "strong acids and bases" - but what do we mean when we talk about "strong" or "weak" acids and bases? We'll spend more time with those concepts in the next lesson, but it will be helpful to have a working definition to use for now.

A strong acid (or base) is one which dissociates completely when dissolved in water.

Strong acids include HCl, HBr, HI, H2SO4, HNO3, and HClO4. All other acids you will encounter in this course are weak acids.

The strong bases are NaOH and KOH. All other metal hydroxides are either insoluble or only slightly soluble. Ammonia, too, is a weak base.

Weak acids will dissolve in water but do not dissociate completely (usually very little, in fact). Weak bases and insoluble salts usually do not dissolve at all, or dissolve only to a small extent. The major exception to this last statement is ammonia which, although it is a weak base, does dissolve quite readily in water. It does not, however, dissociate. Ionic equations are written to show all of these things correctly.

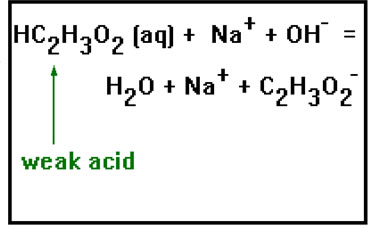

Weak acids, such as acetic acid, do dissolve, but they do not dissociate. In a reaction with a strong base, the ionic equation show the molecular formula of the weak acid, but is shows the base and the soluble salt as dissociated ions. |

|

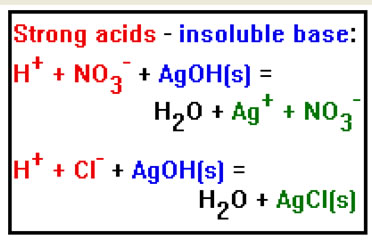

Strong acids can react with insoluble hydroxides, causing them to dissolve. The resulting salt can be soluble or insoluble. In these two examples, silver nitrate is soluble, but silver chloride is not. |

|

There is no easy way to determine what salts are soluble or insoluble. You will usually have to be told or look up each individual salt either in a solubility table or an appropriate handbook. One useful generalization, however, is that all salts containing the sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), ammonium (NH4+) or nitrate (NO3-) ions soluble. |

|

Notice that in this typical ionic equation the anion from the acid (Cl-) and the cation from the base (Na+) do not change in the course of the reaction. They’re the same on both sides of the equation. Ions such as the sodium and chloride ions in this reaction equation which are present but do not participate in the reaction are called “spectator ions.” The spectator ions are the ones that are left out of the net ionic equation. |

|

Exercise 13 shows an example of the molecular, ionic, and net ionic equations for several different reactions of strong and weak acids with strong and weak bases. Look these over carefully and then try your hand at Exercise 14; you may check your answers below.

Answers to Exercise 14:

14. a. molecular: HNO3 + NH4OH

![]() NH4NO3 + H2O

NH4NO3 + H2O

ionic: H+ + NO3- + NH4OH![]() NH4+ + NO3- + H2O

NH4+ + NO3- + H2O

net ionic:

H+ + NH4OH![]() NH4+ + H2O

NH4+ + H2O

b. molecular: HBr + KOH ![]() H2O

+ KBr

H2O

+ KBr

ionic: H+ + Br- + K+ + OH- ![]() H2O + K+ + Br-

H2O + K+ + Br-

net

ionic: H+ + OH- ![]() H2O

H2O

c. molecular: HClO

+ NaOH ![]() H2O + NaClO

H2O + NaClO

ionic: HClO + Na+ + OH-![]() H2O + Na+ + ClO-

H2O + Na+ + ClO-

net

ionic: HClO + OH-![]() H2O + ClO-

H2O + ClO-

d.

molecular: HBrO3 + LiOH  H2O

+ LiBrO3

H2O

+ LiBrO3

ionic : HBrO3 + Li+ + OH- ![]() H2O + Li+ + BrO3-

H2O + Li+ + BrO3-

net ionic : HBrO3 + OH-

H2O + BrO3-

Lab Work

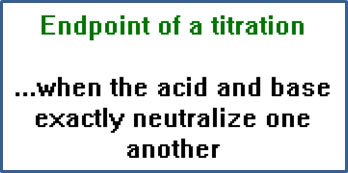

In a titration, solutions of acid and base are mixed until they just neutralize each other.

This occurs when the number of H+ ions from the acid is the same as the number of OH- ions from the base.

In doing the calculations, you will have to take into account the fact that when a multiprotic acid and/or a multibasic base are involved, this does not necessarily occur when the number of moles of acid and base are equal. As you will see, however, using equivalents and normality automatically takes care of this complication.

When the volume of the solution you add is just enough to exactly neutralize all of the solution you’re titrating, the titration is said to have reached its endpoint. |

|

|

To detect the endpoint, we add to the acid a small amount of a chemical called an indicator. The indicator is colorless in acid, but turns pink when the solution becomes basic. In the titrations you will perform in the lab, the base solution is slowly added to the acid. A titration can actually be done either way. We have chosen this way because for the procedure you will use, adding base to acid makes the endpoint a little easier to determine accurately. |

The indicator usually does not turn pink until there is a slight excess of base present. This excess is so small, however, that when the indicator just turns faintly pink, you will have passed the endpoint by no more than a fraction of a drop – just a few hundredths of a milliliter. We will ignore this very small error.

The indicator we use is called phenolphthalein (pronounced “feen – ol – thay – lean”).

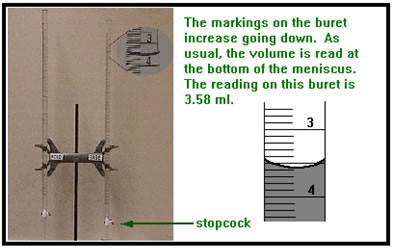

You will dispense both the acid and base solutions from a long, calibrated tube with a stopcock on the bottom called a buret. Look closely at the picture. The volume of liquid in the buret is measured from the top.

|

|

As usual, you read the volume at the bottom of the meniscus. Each time you dispense acid or base solution from its respective buret, you will need to read a beginning and an ending volume. The volume of solution delivered will be the difference between the two readings. It is not necessary to begin each time at the 0.00 mL mark.

In practice, the volumes can be measured to the nearest 0.01 mL. Since the volumes measured are typically between about 20 and 40 mL, this means a titration can theoretically be accurate to about 0.05%, or one part in 2000. You will do well in the lab if you are accurate to about 0.5% or better.

Be sure to take each volume reading from your burets to the nearest hundredth of a milliliter (.01 mL).

You should also have each of these volume measurements recorded to four significant digits. To do this, you must be sure that you use more than 10 mL of each of the two solutions in your titration.

Detailed instructions for performing a titration are given in your workbook and the instructor in the lab will help you as well. Be sure to read through the instructions in your workbook before coming in to lab. Titrations are not difficult, but the procedure includes many details to which you must pay close attention to avoid introducing errors into your results. You are being graded on the accuracy of your results this week, so don't rush through this experiment.

This lab can take quite a while, as you must perform several titrations in the course of the exercise. Be sure to allow yourself at least two hours to do the lab. You may work in groups (of no more than 3 people per group), but each student must turn in an individual lab report. See the Wrap Up section for more details.

In the final part of this lesson, we'll examine the calculations to be performed with the data you collect from a titration experiment.