Lesson 5: Atomic Structures

When we learned about the classification of materials in an earlier lesson, we learned that if you have a material that is a pure substance that cannot be separated by physical means and cannot be separated by chemical reactions, then you have an element. Samples of an element are made up of atoms. In this section, we'll start our look at the inner structure of the atom. We'll start with the subatomic particles, electrons, protons, and neutrons, and then look at the mass of an atom (the mass number), how the particles are arranged in an atom (its structure), and what determines an element's identity (the atomic number).

Electrons | Protons | Neutrons | Mass Number | Structure | Atomic Number

Electrons

All atoms (except hydrogen)* consist of 3 kinds of particles: protons, neutrons, and electrons. The properties of an atom – its mass, its charge, what element it is, what isotope of that element it is – are completely determined by how many of each kind of particle it has. The chart below lists the basic properties of these three particles.

The unit of mass you see in the chart, amu, is an “atomic mass unit.” For now, just consider this an arbitrary unit of mass that is appropriate in size for things on an atomic scale, like protons and neutrons.

(*Most hydrogen atoms do not have any neutrons. A small percentage, however, have either one or two neutrons and the majority of those have only one.)

Electrons are the smallest and the lightest of the three particles. Compared to the protons and neutrons they have practically no mass and so contribute essentially nothing to the mass of the atom. An electron actually weighs about 0.00054 amu. This is so much less than the mass of a proton or a neutron that the mass of the electrons is ignored in determining the mass of an atom.

But electrons do have a negative charge, so determining the net charge on an atom requires that you know how many electrons it contains. Electrons have been arbitrarily assigned a charge of -1.

Protons

Protons are 1,837 times more massive than electrons and contribute up to about half the mass of the atom. They also have a positive charge, the opposite of electrons. The attraction between these unlike charges and the repulsion between like charges is responsible for the chemical properties of atoms.

The charge on the proton is +1. The proton has a mass of about 1 amu. In grams, this amounts to roughly 1.66 x 10-24 g, about 1837 times the mass of the electron. By comparison, the earth is about 81 times more massive than the moon, but the sun is roughly 333,000 times more massive than the earth.

Because protons and electrons are the only charged particles in atoms, we find the net charge on an atom by comparing the number of protons and electrons. When they are equal, the atom is neutral. An atom with one more electron than protons would have a net charge of -1. An atom with one electron fewer than protons would have a net charge of +1. These charged atoms are called ions.

net charge = (# of protons) - (# of electrons) |

Atoms are neutral. (net charge = 0) |

Ions have a net charge, either positive or negative. |

Atoms become ions only by gaining or losing electrons. The charge on an anion {pronounced AN-ion}, or negative ion, is equal to the number of extra electrons it has gained. The charge on a cation {CAT-ion}, or positive ion, is equal to the number of electrons it has lost.

Neutrons

Neutrons, as the name implies, are electrically neutral. In fact, they consist of a proton and an electron stuck together. Since electrons weigh almost nothing compared to protons, a neutron weighs almost exactly the same as a proton. Therefore, the mass of an atom is determined solely by the number of protons and neutrons it contains.

One obvious question to ask is why all protons and electrons don’t stick together to form neutrons. Basically it because the electrons have a great deal of kinetic energy and so “orbit” the nucleus. (They don't really orbit the nucleus, but we'll get to those details later.) The situation is analogous to the planets and the sun. The sun’s gravity attracts the planets, but (fortunately) they don’t fall into the sun because their high velocity keeps them in orbit.

Mass Number

The mass of a proton is given a special name, the atomic mass unit, or amu for short. Since protons and neutrons weigh almost exactly the same, a neutron also has a mass of about one amu. Therefore, measured in amu’s, the mass of an atom is just about equal to the number of protons plus the number of neutrons it contains. This number is called the mass number of the atom.

| The mass number is: | The approximate mass of an atom in amu. |

| = (# of protons) + (# of neutrons) |

The mass number is very close to the actual mass of the atom in amu but it is not exactly equal to the mass for three reasons:

- The electrons, though very light, do weigh something.

- The mass of the proton and the neutron aren’t exactly 1 amu. The proton weighs 1.0073 amu and the neutron weighs 1.0087 amu.

- When protons and neutrons bind together in a nucleus, some of their mass is converted to the energy necessary to hold them together.

Structure of an Atom

Even though protons and neutrons are much larger than electrons, they occupy very little of the volume of an atom. They are bound tightly together in the center of the atom in a tiny ball called the nucleus. So the nucleus contains virtually all of the mass of the atom and all of its positive charge.

| The size of the nucleus in this diagram is exaggerated so it can be seen. If we enlarged an actual atom to the size you see on your screen, the nucleus would be only about 0.00007 inches across, many times too small to be seen with the naked eye. |  |

Even though they are much smaller and lighter than protons and neutrons, the electrons occupy most of the volume of the atom. They are in rapid motion within a large volume surrounding the nucleus, much like the planets can be found in a huge volume of space surrounding the sun.

To put the relative sizes of the atom and its nucleus in proportion, if the atom’s diameter were the length of a football field, the nucleus would be about the size of a large grape seed sitting on the 50 yard line – about an eighth of an inch across. The huge volume of the atom would be almost entirely empty space within which the electrons – too small to see and weighing less than a speck of dust each – would be flying around at high speed. (Need some more visuals? Try checking this out. Or this.)

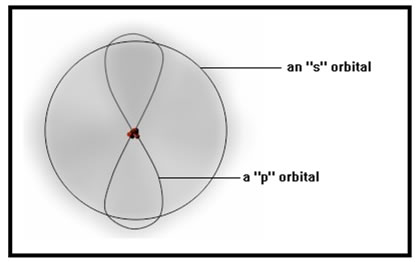

Unlike planets, electrons don’t move in fixed orbits about the nucleus, but they do occupy well defined regions around the nucleus called orbitals. Later in the lesson, we will see how the shapes and the energies of these orbitals help determine the chemical properties of the atom.

|

These orbitals look like they each contain a cloud of many electrons. In fact, each one can contain at most only two electrons. We picture them as a “cloud,” however, because this best reflects the fact that we can’t specify the path that the electrons follow within the orbital. In fact, it appears that they follow no path at all. A better analogy for electrons is to imagine a vibrating string. The vibrations would make the string seem diffuse and its location hard to determine exactly. In this analogy, however, the electrons would be the vibrations, not the string. |

Atomic Number

And what determines what element an atom is? The identity of an atom is determined solely by the number of protons in its nucleus, the atomic number. All atoms of a given element, no matter how they may differ otherwise, have the same atomic number.

atomic number = |

# of protons |

The atomic number of an element is always shown in periodic tables. It is the whole number, usually the number in the largest font, in each square in the table.

| Atomic Number (number of protons) | Element |

1 |

H |

2 |

He |

3 |

Li |

4 |

Be |

5 |

B |

6 |

C |

7 |

N |

The atomic number is the most fundamental property of an element. A zinc atom, for example, can gain or lose electrons and it is still zinc. It can have more or fewer neutrons and still be zinc. But if it changes the number of protons it has, it is no longer zinc, it is a different element with different chemical properties.

Two atoms with the same atomic number are atoms of the same element, but they may still have different numbers of neutrons and therefore different masses. Such atoms are called isotopes. All elements have more than one isotope. Hydrogen, for example, has three, one with no neutrons in its nucleus, one with one neutron, and one with two neutrons.

Many of the isotopes of each element are unstable, that is, their nuclei spontaneously break apart and become other elements. Such isotopes are said to be radioactive. Ordinary matter, the matter we deal with every day, is made almost entirely of isotopes that are stable. There are common uses of radioactive isotopes, however. They are used in medicine to kill cancer cells and to help take pictures of the interior of the body, in home smoke detectors, and, of course, in nuclear power plants and nuclear weapons.

In the next several sections of this lesson, we’ll look at some of the experiments that led to our current ideas about the nature of atoms and the particles they are made of.