Lesson 5: The Bohr Model

In chemistry, the most valuable use of atomic spectra has been to explore how the electrons are arranged in atoms and molecules. When spectra were first investigated, it was known that different colors of light corresponded to different amounts of energy, but it was not known why atoms could emit and absorb only certain amounts of energy.

The energy of light is related to its color. The color is determined by the frequency of the light waves. Red light has lower frequency, and therefore lower energy, than blue light.

In 1913 Niels Bohr proposed an explanation. He knew that the electrons occupy a large, empty volume of space around the nucleus like the planets do around the sun. Theoretically, a planet can be any distance from the sun. Bohr proposed that for electrons, only certain, specific distances were possible.

The essence of Bohr’s idea was that an electron, like light, had a wavelength, and that the only orbits it could be in were those that had room for a whole number of wavelengths. For example, if the wavelength of an electron were 2 nm, it could only fit in orbits that were 2 nm, 4 nm, 6 nm, etc., in circumference, but not in an orbit with a circumference of, say, 3 nm.

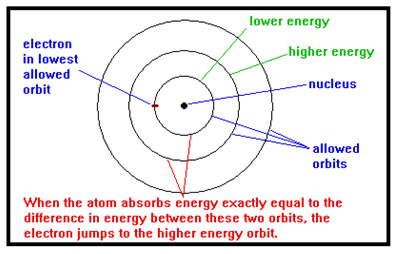

Bohr further suggested that each “allowed” orbit had a different energy – the further from the nucleus, the higher the energy. When an atom absorbed energy, an electron moved from a lower energy orbit to a higher energy orbit. Since only certain orbits were allowed, only certain amounts of energy could be absorbed – amounts corresponding to the differences in energy between the allowed orbits.

Light consists of electric and magnetic vibrations. An electron can be thought of as a vibrating, electrically charged particle. The interactions between the electric vibrations in the electron are what enable the electron to absorb and emit light as it moves from one energy state to another. If an electron is vibrating at a certain allowed frequency and can vibrate at another allowed frequency by absorbing energy, Bohr said that the frequency of the light absorbed must exactly match the difference in frequency between the two allowed vibrations of the electron.

When electrons dropped from higher to lower energy orbits, energy was emitted as light. Since only certain orbits were allowed, only certain amounts of energy could be emitted – amounts corresponding to the differences in energy between the allowed orbits. Example 13 in your workbook has a simplified diagram of Bohr’s model.

When an electron moves from a state of faster vibration (higher energy) to a state of slower vibration (lower energy), the light emitted has a frequency that exactly matches the difference in frequency between the higher and lower states. (Want to see this "in motion?" Try this link.)

Bohr’s model correctly predicted the spectrum of hydrogen. It also explained why different atoms showed different spectral lines: their different atomic numbers would alter the energies of the allowed orbits. The Bohr model failed to correctly predict the spectra of atoms with more than one electron. That would await the development of wave mechanics.

Bohr’s model also made correct predictions for the He+ ion and for the Li2+ ions, ions that each have only one electron. It was the interaction between electrons that Bohr’s model did not correctly take into account.

In the next section, we'll examine atomic spectra and discuss your lab work for this week.