Lesson 5: Spectra

To do the lab exercises for this lesson, you need to know a little bit about light. White light consists of all the colors of the rainbow mixed together. When it is passed through a prism or a diffraction grating, the colors are separated into what we call the spectrum.

A diffraction grating is a piece of glass or clear plastic into which have been etched a series of extremely narrow lines. If you were to look at a grating, the lines would be too small to see, but you would see a rainbow effect of the surface. Today the most common examples of this effect are music CD’s, video DVD’s, and computer CD-ROM disks. The lines on the surface of a CD are narrow enough to diffract visible light, so that when you look at the light reflected off of the surface, you observe a rainbow effect.

Emission Spectra | Absorption Spectra | Lab Work

Emission Spectra

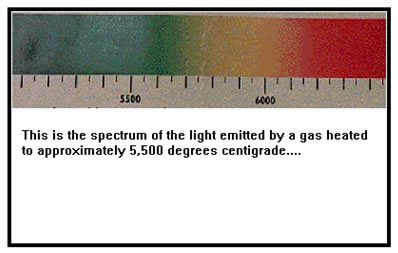

When a material is heated to high enough temperature or when enough electric current flows through it, it will begin to emit light. If this light is spread out, the result is called an emission spectrum – it is the spectrum of the light emitted from the material. |

|

| The beam of a cathode ray tube is the light emitted when the gas inside the tube glows as a result of being struck by fast-moving electrons. An ordinary incandescent light bulb is a common example of light produced by heating a solid – the filament inside the bulb. |  |

Two kinds of emission spectra are possible. One, called a continuous spectrum, has a continuous range of colors. This is the kind of spectrum the filament of a light bulb emits. Continuous spectra are usually emitted by solids. |

|

The range of colors emitted depends on the temperature. At low temperatures, light at the red/yellow end of the spectrum is emitted. Candles burn at rather low temperature, hence the light from the flame appears yellowish. As the temperature is raised, more and more of the spectrum is emitted and the light becomes whiter. At very high temperatures, more light at the blue end of the spectrum is emitted, and the color takes on a bluish cast. The hottest part of the flame of a bunsen burner is a good example of this.

The other kind of spectrum is called a discrete spectrum, or line spectrum. A line spectrum contains on specific, ‘discrete’ colors of light that appear as lines. These spectra are usually emitted by gases.

In the experiment for this lesson, you will heat samples of dissolved metal ions. The spectra that are produced are discrete (line) spectra. This is because the heat of the flame “boils off” small amounts of the metal and it is these gaseous metal atoms that produce the colors you see in the flame. The spectra produced from the flame tests are difficult to see if there is ambient light, so you will be observing the flame colors but not the emission spectra from the flame tests. You will be observing the spectra produced by gas discharge tubes; the spectra produced are more intense and easier to see in our particular lab set-up.

Absorption Spectra

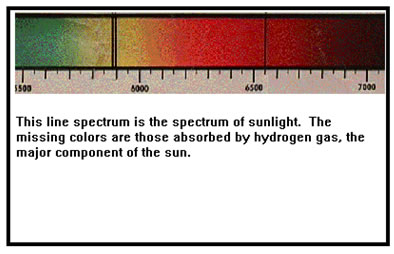

Another way to produce spectra is to shine white light through a sample of material and then examine the light that emerges. These spectra are called absorption spectra because the light that emerges is missing the colors that are absorbed by the sample.

Absorption spectra are usually produced by a “double beam” instrument. Instead of examining just the light that emerges from the sample, such an instrument compares the light from the sample to a beam of light that has not passed through the sample – the reference beam – to make sure that the wavelengths of light that are missing are only those that have been absorbed by the sample.

|

|

Like emission spectra, absorption spectra can be continuous or discrete. As before, solids and liquids usually absorb continuous range of light and so produce continuous absorption spectra, while gases produce absorption line spectra.

Continuous spectra are basically line spectra in which the lines have been broadened. This broadening comes about as a result of the interactions between neighboring molecules. In a gas, the atoms or molecules are very far apart and are moving so fast that when they do collide, they merely bounce off each other, and so no such interactions occur.

Lab Work: Identifying Elements from their Spectra

In the 1850’s Bunsen and Kirchhoff noticed that different elements absorbed (and emitted) different, characteristic colors or light. The earliest practical use of this discovery was to examine sunlight to determine what elements were present there. Since then, atomic spectra have given us valuable clues about the internal structure and arrangement of electrons in atoms and molecules.

Light is the only thing that reaches us from outside our solar system. Examining the spectra of the light from starts gives us valuable clues as to what emitted that light (the composition of stars, their temperature, and their motion relative to us) and what might be in the space between us to absorb some of that light. You are familiar with visible light, and probably also know about infrared (below red) and ultraviolet (above violet) light. But microwaves, radiowaves, cosmic rays, and gamma rays are all forms of light as well. They just have wavelengths that are outside of our eyes’ ability to detect. |

|

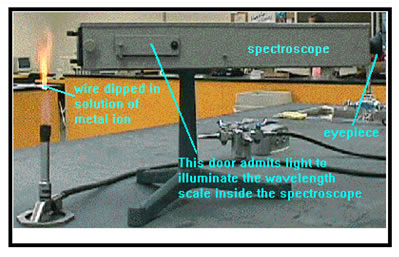

In one lab exercise this week (Ex. 15), you will dip wires into solutions of several different metal ions, then heat them in the flame of a bunsen burner. The heat causes the metal ions to emit light, which imparts a color to the flame. In a dark enough room, you can also observe the light through a spectroscope to see what colors are present in the emission spectrum. You use that information to determine what metal is present in an unknown solution. We are going to use just the flame colors to identify the unknowns.

Cleanliness is very important for getting good results. Do your

best to make sure that you do not contaminate your testing wires.

For example, just a little bit of sodium contamination (even from

your fingers) can disguise the true flame test color for another

element.

In testing for flame colors, it works out best to place the wire low

in the flame and near the outside of the flame. If it's too close

to the center of the inner flame, it won't get hot enough to show

the color.

Some of the metals (like sodium) impart a color to the flame that persists for quite a while. Others (like lithium and potassium) give a brief burst of color. Pay attention to the early colors that you

see.

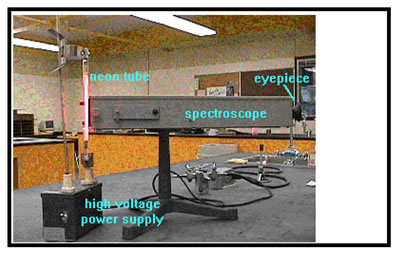

In the other lab exercise (Ex. 16), you will use high voltage gas discharge tubes and the spectroscope to examine the light emitted when electricity is passed through several different gases.

The procedures for both of these exercises is detailed in your workbook. You will write up a lab report in the usual format about both Ex. 15 and Ex. 16, and answers to the questions about each exercise. (You will not have any calculations for this lab report.)

You can find absorption and emission spectra for various elements on the web by just doing a Google search. The University of Oregon physics department has a great site that's worth a look. You can see the absorption and emission spectra of most of the elements on the periodic table. It might interest you to look at the emission (and absorption) spectra for the elements that you observed in the flame test portion of this lab. If you compare the emission and absorption spectra of a particular element, you can see that they are opposites of each other - the colors shown in the absorption spectra are absent from the emission spectra and vice versa.