Lesson 5: Electrons

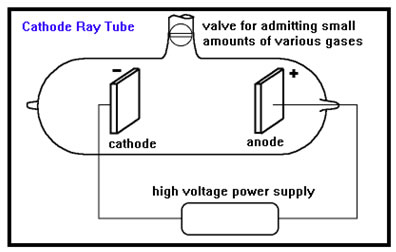

The discovery of electrons was a result of the invention of the cathode ray tube, or CRT. A CRT is a glass tube from which all of the air has been removed. Small amounts of various pure gases can then be added. Inside the tube are two metal plates connected to a high voltage power supply.

A number of other components can be added as well. Often the anode is coated with zinc sulfide, which glows when struck by electrons. Other plates that can be given a positive or negative charge can be placed either inside or outside the glass tube.

Over the years, the simple CRT evolved into the vacuum tube – which ultimately was replaced in most applications, first by the transistor then by the integrated circuit. Other descendents are the picture tubes in televisions, computer monitors, oscilloscopes, and a host of other devices. Even today, the monitor on which you are reading this is often called a CRT. (However, many of these picture tubes are now being replaced by new “flat screen” technologies like plasma screens and LCDs.)

The metal plate connected to the positive lead is called the anode and the plate connected to the negative lead is called the cathode. When high voltage is applied, the gas in the tube between the two plates will start to glow. The color of the glowing gas depends mostly on what gas is in the tube. You are undoubtedly familiar with the red glow caused by neon gas.

In order to get a good effect, there must be very little gas in the tube. When too much gas is present, the flow of current is blocked and no effect is observed (hence the name “vacuum tube.”) In a picture tube, no gas is present and the front of the tube is made of transparent glass on the inside of which there is a phosphorescent coating which glows when struck by electrons.

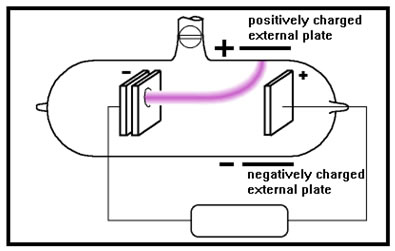

Experiments showed that the glow was caused by a stream of negatively charged particles. In the experiment shown here, the stream of particles is attracted to a positively charged plate placed near the top of the CRT, and away from the negatively charged plate at the bottom.

Additional experiments with magnets confirmed this interpretation. Careful measurements allowed the experimenters to determine the ratio of the mass of the particles to their charge. Heavier particles would have more momentum and thus would be more difficult to deflect. More highly charged particles would be more strongly attracted to the side plates and thus would be deflected more.

Many experiments with various gases showed that the stream of particles was always the same: negatively charged particles with the same low ratio of mass to charge that Stoney named “electrons.” The glow was caused by atoms of the gas being struck by the fast-moving electrons.

The beams of particles produced in this way by the CRT were initially known as cathode rays. In the absence of gas in the tube, they can be detected by placing a phosphorescent screen along their path. The screen lights up wherever the cathode rays strike it, and so it glows all along the path of the particles.

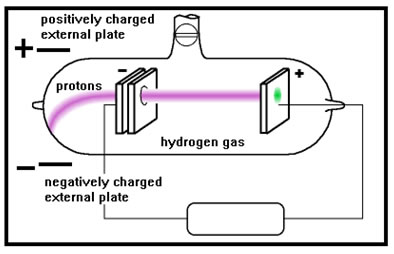

When a hole was made in the cathode, the gas behind it began to glow as well. Experiments with this stream of particles showed that they were much heavier than cathode rays and positively charged. Moreover, their mass/charge ratio changed when the gas in the tube changed.

The positive rays turned out to be positive ions that were formed when the electrons that made up the cathode rays struck the atoms of gas in the tube. When this happened, an electrons could be knocked off the atom, giving it a positive charge. These glowing, positively charged ions were then attracted to the negatively charged cathode. When a hole was made in the cathode, their momentum would carry some of the glowing ions past the cathode, forming the positive rays.

|

The lightest of the positive rays were formed when the gas in the tube was hydrogen. Rutherford decided that these particles were the smallest positively charge particles possible and named them protons. |

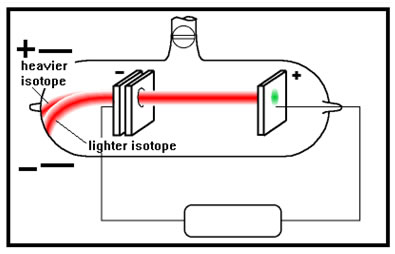

| The first clue to the existence of neutrons came when Rutherford found that neon produced two beams of positive rays. This meant that there were two different “kinds” of neon atoms. The two different forms of neon were named isotopes. |  |

In the 1920’s a chemist named William Harkins suggested that there was a third particle he called a neutron. It was neutral, so wouldn’t change the atomic number, but had mass. The two beams were neon atoms that had different numbers of neutrons and so had different masses.

| The ability of the CRT to separate particles of different mass and charge led to the development of the mass spectrometer. When complex molecules are hit with a beam of electrons, they are broken into a variety of fragments that have different masses and charges. These can be separated in the same way that the two types of neon atoms were separated. |  |

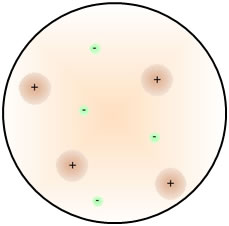

| But before the discovery of neutrons, J. J. Thomson proposed that because like charges repel and opposites attract, the atom must consist of protons and electrons distributed more or less uniformly. This is commonly referred to as the "plum pudding" model of the atom. |  |

In the next section we’ll look at the experiments Rutherford conducted to establish the true nature of the atom.

Thomson’s model was really the only one that made any sense. Yet Rutherford, in the true spirit of science, designed experiments to test it. (The flaw in Thomson's model was something that neither Thomson nor Rutherford could have foreseen at the time. It is that magnetic and electric forces are not the only forces that exist within atoms. But the existence of short range nuclear forces was not known, nor was it expected. It took the rather startling results of Rutherford’s experiments to suggest that such forces even existed.)